ASF is recognizing Black History Month by sharing, for the first time online, four stories from our Winter 2020 issue, which showcased emerging Black writers selected by guest editor and PEN American Robert W. Bingham Prize winner Danielle Evans. Here is author Selena Anderson, reflecting on the experience of writing this story:

The inspiration for writing “A Shameful Citizen” came when I started noticing a few new patterns in my life. I was getting predictive text but with people. I’d go to parties, and I could foresee what people were going to say and how, I knew the style of their jokes, the shows they’d recently binged—and instead of getting curious about our shared algorithms or looking inward or empathizing with the fact that many of us are still going to parties just to blab about how limited we feel in our choices—I became judgy and superior. I felt like a psychic and also hugely annoyed and isolated. In the story, Syreeta’s abilities allow her to go places she’s not supposed to go. They give her insight into what others don’t intend to reveal. This makes her free and trapped, terrified and amused. At the same time Syreeta is constantly surprised—by the girls who visit, her midnight caller, and her sister’s side hustles. It was important to me that the reader have a palpable sense of her frustration and her wonder at it all.

— Selena Anderson

—

Nuclear war? Rising sea levels? Such trifles never worried them. They were less concerned with knowing how and when the bees might return than with tracking down an ex-boyfriend, than hiring the neighborhood oracle to grope across the cosmos for the definitive answers they couldn’t just find on the computer. Mistresses, godmothers, and fiancées. They both called and wrote letters. They showed up unannounced. They pushed an abalone shell full of crinkled bills across the kitchen table and asked the burning questions Syreeta had heard a million trillion times: Do I ever cross his mind? Do he love me like he say he do? Do he miss me at all? When you were in pain, every tense was the present tense.

Syreeta had to affect a thoughtful expression while listening to yet another tale of desperation and fragility. Brew a little tea, burn some sex on the beach. Or—and here’s a thought—dodge responsibility altogether by drawing the moon card, which really just meant that this was a season of possibilities. “There’s a chance for anything,” said Syreeta. Like for Jonetta Paris to recover from one of those twenty-first century earthquake type of loves that had wrecked her finances and relationships with her grandchildren.

“Maybe I’ve lost my mind,” said Jonetta. Her recent choices made it seem possible. She seemed to be looking for her mind, just beyond Syreeta’s ear, in the plants and cased china. “It’s shameful to be asking about this man after he’s cost me so much.”

“Sometimes we turn the pain into a question,” said Syreeta, “so at least we can dance with it.”

Jonetta nodded tentatively. “But I be asking the wrong questions,” she said. “Like, what if God lost the battle in heaven, and He was the one who got thrown into hell? Ain’t that the type of trick the devil would play?”

Jonetta’s line of questioning paired with the glow of Syreeta’s formica’ed kitchen made Syreeta gaze out the window. It had been raining since Tuesday in five-minute maddening intervals so that by Thursday the world was still a ghetto, just a gray one.

“What I’m hearing,” said Syreeta, “is that this love of yours has put your faith in a jail cell? Does it seem healthy to give anyone that kind of power?”

“I think I know what you getting at.” Jonetta crossed her arms and looked at her feet. “But I don’t know if I can call Herbert the devil.”

“Can’t or won’t?”

“Don’t want to.” Jonetta shrugged in a juvenile-delinquent sort of way. Sad how much of it boiled down to looks! If he liked your looks, he came running. If you made yourself the picture of a hopeful, desperate woman on the hunt for love, he hid his face and ran the other way. But in Jonetta, Herbert saw opportunities the shadow of which made him smile. You had to have that kind of smile to convince someone to dip into her grandbabies’ college fund, pawn her minks, and cosign on your small-business loan.

Syreeta raked her fingernails up the nape of her neck, scratching the crown of her head as if refocusing her thoughts. “You don’t want to see the role you play in your own problems, Jonetta. And I get that, because Pluto in Virgo can make anybody want to hide their real feelings. But you’ve got to ask yourself, in your scenario, as you describe it, who exactly is playing the devil?”

Involuntarily, Syreeta looked into Jonetta’s face. She noticed the glowing nose, chapped lips, and false eyelashes that made Jonetta look like a big, middle-aged doll. The most prominent feature was a deep vertical wrinkle folded into the fleshy part between her eyes, visible whether she was frowning or not. The wrinkle gave Jonetta the stunned expression that you sometimes see on people who’d lived in the neighborhood for too long, the exact ones who’d be turning over the same dum-dum questions when the big one struck. Twice a day Syreeta spirited away to the mirror to make sure she hadn’t started looking that way too.

“It’s me,” confirmed Jonetta. “I’m the devil!” Jonetta took Syreeta’s hand in hers, which were surprisingly strong and damp. “I’m the devil,” she said again.

Jonetta’s grip inspired Syreeta to gaze past this woman and the dripping rain to her own reflection in the glass. As she smiled, she saw and felt her face bending in untoward directions. Just a year prior, a mere thousand questions lighter, Syreeta hadn’t noticed that her face could do such a thing, but now she was accidentally seeing things about herself all the time. She made a fast adjustment, raising her nose like a rich woman smelling something foul. Once the funk cloud dissolved, Syreeta sent a clear thought to her own eyes: I still look good.

All this sneaking and judging had turned Syreeta into a nerved up, testy snob, miserably critical of herself and others. Excessive meditation on other people’s drama had made her desperate for her own. Since she had none, she’d come to overvalue her own feelings like precious family heirlooms. Her feelings gave her conflicting feedback when in exuberant scolding tones they gossiped that her God-given talents were being underutilized in this kitchen.

Who knows what good she could be doing, said the right side, with the right publicist? A little coaching. She could give us the evacuation routes before the storm hits. She could be saving lives.

She couldn’t save a life with a life raft, said the left side. And she shouldn’t try. Syreeta know good and well she ain’t no psychic.

It wasn’t exactly second sight. Syreeta wasn’t sure what to call this ability to gaze at a stranger across the table and at the same time sneak into the hidden regions of the heart, opening all the safes, garbage chutes, and mailboxes. She found the secret meaning in other people’s quiet looks, and this knowledge made her rich in correctness, an expert at being right. Syreeta’s true gift was being 100 percent right 100 percent of the time. This was how she knew when a fire would start and why, if a suicide went unattempted, when a drug deal would go left. She could tell from the freshness of your fade how close you were to eviction. The way you walked into a room told her all she needed to know about your relationship with your father. She gave vivid descriptions of past lives, explained the motives of parents who in this world just couldn’t say aloud that no, they weren’t necessarily proud of their children per se, but without question they loved them anyway. She watched her open-mouthed clientele as speculation became reality.

But now Syreeta had been looking in the mirror. She’d been listening to her feelings. She’d had the gift all her life, and somewhere between reading palms, cards, and minds, the champagne feeling of being completely right, every time, was running out. She worried that she was faking it and telling the truth anyway. Just once she’d like for somebody to tax her abilities by asking when the stars would fall or what scientific magic the little girls of the future wound up using to stitch the ozone back together. Who knows what she could do if given the opportunity? Someone just had to ask.

Her sister, Nedra, had more of a carpe-diem outlook on things. Nedra walked into the kitchen holding the baby, wearing dolphin-hemmed shorts and a sports bra, half her hair braided down into tight cornrows, the other half a mandala of black nettles. She sat down and handed off Armani, who was already cycling the air for Syreeta.

“I have a question,” said Nedra. She placed the abalone shell on her head like a fascinator and pretended to look surprised. “Can you teach me the dark arts?”

“No,” said Syreeta. She bounced Armani on her knee, rowing him from side to side. “And stop asking.”

“You need an apprentice,” Nedra persisted. The chair whined as she pulled herself closer. “And you know I’d be the model student because I only need to learn one thing. It’s a very specific thing. I just want to know how to read faces—the kind you can’t ignore. I want to know why you’d make that kind of face. What exactly crosses your mind when you’re doing it, and how you get people to look at your face more than all the others.”

Syreeta pointed her toes and slid Armani down a fallen tree. She wheeled him up again until she could not get him any closer. Feeling his giggling, breathing ribs, she said, “Something tells me that your motivation has to do with a man.”

“It does,” said Nedra, glancing around for invisible conspirators. “But why you judging? You need to teach me to see things the way you can—just a little bit.”

Syreeta eyeballed her sister. Nobody had ever got onto Nedra about the way she held a pencil, and now when she wrote a letter, her hand looked like a lobster that was trying to get away. She had country, anachronistic tendencies, always throwing stuff in the trash that went in the recycling. She was impossible to offend, only silence could do the trick. She’d fall into the gutters for a trifling man, and once it ended, she’d take up with his other girlfriends just to soften the blow. Yet Nedra, she was happy, she had joy. The thought made Syreeta’s ears burn.

“No,” she barked. “And that’s that.”

Nedra curled her mouth, leveled her eyes. “That’s cause you stingy!” she said. “What’s a gift if you don’t give it?”

The doorbell played the Westminster chime: it was the sister mamas and their brood, Nedra’s chosen people toting action movies and synthetic hair. Armani scrambled off Syreeta’s lap, making an ecstatic, almost tortured sound as he ran to greet them.

Like a traveling daycare, they took a pleasure trip across the house, their children playing slaps and catwalking up the hallway. It made Syreeta timidly hopeful to see them dance their choreography, perform their interpretation of grown, fed-up women, when not long ago they’d been little babies, and before that, they were all at a microscopic cross-roads, a thing to be dealt with or embraced.

The sister mamas changed the radio station and pulled up chairs to talk bad about another woman they had all grown up with. Syreeta eavesdropped, watering a plant as an excuse to linger. She had been doing this lately since it was the only way to enter their conversations unobtrusively. She wasn’t sure why she had started or how to stop.

“I don’t know what she was thinking with that outfit?”

“Like a box of crayons. You’d sprain your eyeballs looking at her.”

“And don’t get me started on those toes. Reminding me of the Toeskegee Airmen.”

“Must think she’s Toesephine Baker or somebody.”

“Maybe Edgar Allan Toe.”

Syreeta glanced down at her own feet, thinking irrationally that they could be talking about her.

“Toes look like they in a race and everybody’s losing.” They laughed, holding each other by the elbows. Syreeta floated past them shaking her head.

She found it remarkable that these ladies could laugh together when their badass little cherubs shared a father. Tommy had taken the command be fruitful and multiply to heart, but otherwise he lived like a Corinthian. He sold bootlegs and switchboards he’d saved from dumpsters, but movies had convinced him that the real money was in endangered animals. So, Tommy bootlegged them too until he got busted peddling local rodent lookalikes of agoutis and woodrats to rich girls. The judge conceded that although Tommy had the heart to do it, he hadn’t really contributed to the overpopulation of exotic animal friends, but still, wrong was wrong. He’d be serving precious time in the Huntsville penitentiary until the youngest finished college.

Occasionally, the sister mamas commented on their lot in life: they’d all made eternal sacrifices for the same man, had their hearts molly-whopped in a nearly identical way. Now they were left to raise his babies alone together. What happened?

“Oh-well-you-know . . . Love’s got a mind of its own.”

“He gave me category-five migraines.”

“We failed to have a meeting of the minds.”

“What minds?” Syreeta would love to say, but then Cheryl Thomas, a constant walk-in, was knocking on the door and turning the knob, shaking out her umbrella and pulling up a chair.

“Look, I know I ain’t got no appointment and you’re a very busy woman, so I’m a cut straight to the chase. I just don’t know what to do with these ashes. My husband’s. For the memorial, I put them in an urn, right? That’s what you do. Then I gave some out to family and friends, almost like a party favor. But it wasn’t finished there. It was so much left. So, I put some in a teddy bear. I sprinkled some in the Gulf of Mexico. I took a pottery class and put some into these sculptures I made.” With her manic hands, Cheryl drew firecracker flowers or a sacred heart exploding. “It’s like I can’t find the right place to put them or something. And I don’t know who to give them to.”

“You want to give them to your husband,” said Syreeta, “since they belong to him.”

Cheryl brought a fist to her mouth as she choked back tears. “This has been weighing on me,” she said. “It’s not supposed to be that easy to figure out.”

Syreeta gave Cheryl a discount on a few crystals to absolve her of certain thought patterns and threw in a printout of the serenity prayer for free. She even walked her out the door, and seeing the sky bowing with leaden tumorous clouds made her heart tingle. These clouds had so much room, so many choices, yet they were heading straight her way.

Bombs of ill-timed female laughter erupted from the living room. Glancing over her shoulder, Syreeta saw a hair salon at eight o’clock. The sister mamas had turned on gospel and soap operas and were shouting, “May I say!” and “I must say.”

Yeah, yeah, yeah, Syreeta told herself. Y’all having y’all say.

But when the sister mamas traipsed back into the kitchen, she felt her sense of empathy dismount and crash. Ronnie spoke on behalf of the collective. “A little pro-bono reading, perhaps?”

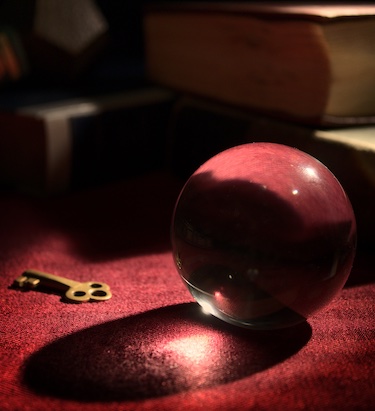

Perhaps. Per all the haps in the world. Syreeta gazed from one sister mama to the other. Fastening her eyes, she took a deep breath and clapped her hands against the cool hips of her crystal ball.

“I see a picture frame,” she said flatly. “Inside are four twin beds arranged in a semi-circle.”

“That’s for us,” said Kelly. She and the others hunched inward. “A bed for each one of us.”

“There’s a banner above the beds. But I can’t tell what it says. There’s a storm coming. The clouds are reaching in—”

“Go back to the banner,” said Nedra. “What’s it say?”

“Oh, look! The storm is passing. The rain dries up. The sun burns off the clouds. The banner . . . it’s all a blurry mess, I can barely read it. But it’s a name. For a woman named after her father.”

The sister mamas leaned back in their chairs, throwing each other starved glances. “That could be anybody.”

“Now the sun is setting. It’s opening like a door. Who’s this? It’s a man with lots of ideas. He has smooth skin and pretty eyes.”

“Sound like Tommy. Is it Tommy?”

“Another bed is floating in, knocking the four twins out the picture frame. It’s a California king with gold satin sheets. The man is seated on the edge of the bed and is unlacing his shoes. With one hand, he’s pulling off his shirt. He puts his retainer in his mouth and climbs into bed.”

“Go on! Go on!”

Glancing at the sister mamas, Syreeta felt a twinge of jealousy. Group anticipation had given them something more valuable than oil. As long as they were waiting, together, anything in the world was possible. Nedra had the glow too, and it made her look like a stranger.

“Now there’s four women in the bed,” said Syreeta, her voice growing soft and secret, which only made the sister mamas more interested. “He looks at them all scratching his chin, wagging his head. He’s eyeballing, whistling, nodding, licking his lips. He’s coming to a decision. He’s making that life-altering choice. And then he steps forward, reaching a hand to one of the women—”

“—Which one?” they said together.

“Damn,” Syreeta whispered. “It’s gone. The clouds are back. It’s so crowded in here, anyway. So loud. All this rain and noise and clouds. Will they ever blow away again?”

“Well, it’s been raining all week,” said Kelly. “We’re lucky she can see anything.”

“Yeah,” said Ronnie. “We’re lucky for Syreeta.”

Ronnie was still watching Syreeta. She was resting her chin into a curled hand as she leaned forward, implying with her sidelong looks, You think you slick. Syreeta glanced away at the ceiling and told herself, I mean . . .

—

It continued to drizzle late into the night, and the moonlight that poured across the windows seemed hunted and reaching. Syreeta dropped an ice cube into her glass of Chablis and walked up the hall to her bedroom, feeling her brain pulse in her head. She switched on the television to watch her favorite cable news channel replay footage she’d already seen. America was a mishmash of mayhem and disaster: hurricanes traveling in threes like witches; forest fires wolfing down entire cities; dormant volcanoes behaving apocalyptically; hundred-year floods striking biannually. The good news was that there had been a medical breakthrough! A cosmetic surgeon spoke to reporters about a revolutionary pill, currently in clinical trials, that promised to make you live longer.

“Do it come with its own planet?” Syreeta asked the screen. She watched and drank and shook her head.

Eventually her mind leaned into sleep, shuffling the faces she’d been mugging at all day. When the phone rang, she woke, jerking her legs as if she’d been flung from the top floor and was sprinting frantically across the sky. She carried these anxieties over the line as she answered, speed-listing her credentials.

“That’s impressive,” said a man’s voice: velvety, local. “But I already know who you are.”

Syreeta dabbed two fingers against her pulse until she became as chill as she was ever going to get. “Everybody knows me,” she said. “I’m like a movie star.”

“You are a star,” he said. “That’s why I’m even calling. I’m trying to get like you. Think you could train me?”

Syreeta leaned on an elbow, peeking past his voice into his house, which was filled with air plants and high-gloss wooden furniture. The thermostat was set to a conservative seventy-five degrees. Emotive music was playing. The bathroom door was open and inside Judah Walker, a black man in a red bathrobe, was sitting on the edge of the tub, a highball in reach. When he saw Syreeta looking, he saluted her. Icy vines of shame snapped in her ears and whipped down the length of her back. Nobody had ever done that before, she had never been caught breaking in. Judah scooted down a space so that Syreeta could sit with him. If he hadn’t, maybe she could have hung up the phone and returned to her nightmares.

“Is that why you’re calling me?” Syreeta said. “Because I’m a star.” She had intended to affect a tone of sleepiness to shame and alert him to his own interruption. But the problem was that she sounded game, not sleepy. Judah could hear it.

He laughed like an out-of-tune organ, all staccato Gs and Ds. For some sad reason, she liked that too. “You doing it right now,” he said, “ain’t you? You’re looking at me.”

He was tippling his glass, eyeballing her over the rim. It struck Syreeta that she had finally been caught but by a man she felt, with little tremors in the knees, was beneath her. She kind of liked it. He had a bachelor’s in accounting, had never been married, and was the father to twin boys. His favorite dessert was sweet banana pudding served hot.

“It’s like you already know me,” said Judah. “You can see why I want to catch up?”

Outside Syreeta’s bedroom window the night sky seemed riddled with buckshots. A pair of girls walked up the street like their car had broken down. After they had turned the corner, Syreeta watched to make sure nothing but storm winds were following them. Returning to the call, she said, “If you ain’t got no money, Mr. Walker, you’ve called the wrong number.”

“Well, hold on now. Let me read you. And if I’m right, let me read you again tomorrow at midnight.”

“After you’ve had a bubble bath.”

“That’s right! You are really something. Me, on the other hand? I’m just learning the trade. It’s easier once I get talking.”

The air shimmered with the nacred brilliance of erotic chemistry, but Syreeta told herself it was only Judah’s candles.

On television it was hunting season. A doe stepped into the forest with stunning grace. Syreeta turned the volume down to a murmur. The instant the shot rang out, the doe jerked left, leaping painfully off screen. For a moment Syreeta thought she’d gotten away.

When she looked at Judah again, he was stroking the length of his beard. He had on white socks and sandals, and his robe was glowing red. His nostrils flared and gazed up at her like a second pair of eyes. He was stamping himself all over her nerves.

Still, she had to ask him, “What do you see?”

“You’re beautiful in the classical sense. Tall. Symmetric and everything. Thick hair too. But you have a complex about your behind or your forehead.”

“Something like that,” said Syreeta. She poked her feet from beneath the sheets to let her toes breathe.

“You ain’t got no man, but that’s by choice. That’s what you say. You got enough of your own problems to be taking on another person.”

“Everybody has problems,” Syreeta said, a little curtly. “Nobody without problems would take a call from a stranger in the middle of the night.”

On television the hunting pro snapped pictures as a father and his son posed with a buffalo carcass. Syreeta turned the channel to an infomercial where a pair of fair, feminine hands theatrically spilled milkshakes and spaghetti sauce. Before the television could reveal the product that would prevent such accidents, Syreeta turned again, this time to a split screen. On the left side children were throwing their shoes at American tanks. On the right, a woman holding a microphone stood alone in the dark to talk about it.

“You’re desperate for something,” said Judah. “I can’t tell what it is, but I appreciate desperation in pretty women.”

This pleased Syreeta anyway, because she loved more than anything to be regarded with contempt. “I see you, too, are at a crossroads,” she said. Her voice had taken on a flirty bounce that she could do nothing about.

Judah winked and turned to put on some Alice Hailey, a little seduction by clarinet, from a recording that was supposed to have been lost in a fire back in the fifties. “I love the way you pivot. Say, what sign are you anyway?”

“I’m a stop sign,” said Syreeta.

On the edge of the bathtub, Judah shook his head. The tiny window above blinked with violet light. He raised his glass and took a good, swallowing look. When he reached the point where he was unable to go on observing silently, he said, “You’re bigger than that. You got to deal with big ethical dilemmas. You got to jump into people’s minds willy-nilly to tell them what they know, charge them for your time, and then wonder what it makes you. What does that make you?”

In a way, it made Syreeta the most honest woman alive to be so deliberate with everyone all the time. But her heart didn’t buy it. That was the part that burned with something worse than guilt: exposure.

“I guess we’ll see.” Syreeta hung up the phone quick. But the appointment had already been made, and she had not missed a day of work in over seven years.

—

Waltera’s daughter, Nova, liked to dress like a rapper in haute couture makeup. She wore starched jeans that bunched like an accordion at the ankle with coral eyeshadow and Penny Hardaways. Her hair was stacked in a complicated configuration of buns with chopsticks poking out and baby hair calligraphed down the sides. In the kitchen corner, Nova took one hundred plus pictures of herself, making the best use of storm lighting and plants, only speaking up to interrupt her mother’s reading with scorn. Otherwise she was rolling her eyes, making baby avatars on her phone, giving her digital children the show-stopping names of Zimara Nicole and Apollonia Rose. She could go sunrise to sunset playing games, the simulated type with no objective—just be more unique or at least filthy rich. In the fantasy, Nova was on her way. A teenage lothario, she had a whole second family: two post-racial daughters and a wealthy, Nordic husband.

“The sun won’t be in sync with your power planet until next year,” Syreeta informed the mother, “but just hold on. You’ll eventually get the recognition you’ve been desiring.”

“What about my love life?” said Waltera, secretly checking Nova’s face for even the smallest sign of disgust.

“You have Venus in your sixth and seventh houses,” Syreeta told her. “That makes it hard for you to trust people, but at the same time you can’t stand being single.”

Nova cackled without looking up from her phone. “Sounds like you’re screwed.”

“I’m warning you girl . . .”

“It’s just a tough time,” said Syreeta. “One of those phases. Part of your life seems to be slapping you in the face, which means a drastic change is on the way.”

“Did you tell her our house is in foreclosure?” Nova’s eyes, cool and black as a camel’s, suddenly, suddenly made her seem doomed.

“If you don’t stay out of grown folks’ business . . .”

“—You think I want to be grown?”

After Waltera yelled for her to get in the car, Nova took her time getting up. She walked slow, swishing her high, compact ass and glaring into her phone at the life she deserved.

Friday was a busy day. Cheryl returned with the gift of ashes. Then Merline came with her own explanations. She said that when the U.S. government changed its currency to gold, it had a profound effect on the people’s consciousness, but now because everyone used debit cards, they’d become miserable again. Post appointment, Syreeta’s mind felt empty and starved. When a thought transpired, it was this: Maybe I don’t like people enough to help them.

And then Jackie came jingling her car keys. She was talking and talking, no end in sight. Syreeta listened to the beeping garbage trucks along the boulevard and the timid predictions of the weather man on television. Another storm was coming and even recent history couldn’t predict his temperament. Jackie was still talking, channeling her anxiety into her keys. Syreeta looked hard at the rounded planes of her face, her lipstick, her topography of finger waves that didn’t budge in spite of her movements. What in the hell was she talking about? And why couldn’t she stop? Why couldn’t she leave? Matter of fact, why couldn’t she throw dust, poof, and disappear?

Half the day had burned off when the mail arrived. Between the bills and sale pages was a postcard that would pull on your heartstrings if you had a heart.

Dear Miss Syreeta, I’ve been divorced for over a year now, and I want you to know that I owe it all to you. I could never have done it without you. In my eyes you’re a Godsend, and I mention your name to every married woman I meet. You have changed me. I thank you. Best regards, Claudia Fielder

Syreeta stood over the sink, pinching the corners of the postcard between her fingers. She stuffed the postcard down the drain and flipped on the disposal.

And then two gawky dark-skinned girls showed up when they should’ve been in school. Tenderonis. They had rhyming names and inscrutable, striking faces, and they sat close together, like one was trying to recline into the other and disappear. Syreeta loved the girls right away. She’d always loved young people who kept their biggest, most embarrassing hopes a secret. The girls told Syreeta how they’d been planning to start a pregnancy pact to keep the men away, but one of them kept backing out. When Syreeta looked to see which, they blocked her by thinking of the same thing, of Praslin Island, which they’d seen on a stepfather’s computer. They were too wise to ask Syreeta about the future, but she looked anyway, into a room upholstered in salmon velvet. It was early spring with soft lights falling in diagonals, and the girls were themselves but pregnant now, braiding each other’s hair. It took Syreeta a moment to realize this, but they had misled her here too. This was their hope for the future room, not the inevitable future room. That one was still a secret.

Syreeta counted her money and felt the muscles in her face go slack from disappointment. How did that poem go? That life goes on for just a minute? Didn’t seek it, didn’t choose it. But it’s up to me to use it. Just a tiny little minute, but eternity is in it.

Nedra, the sister mamas, and their team of little hellions charged through the front door and down the hallway into the kitchen. The women made a ceremony of gathering around Syreeta at the table, each of them taking on the alert, goofy demeanor of someone trying hard to hold in gossip. Nedra had nestled herself into the crowd and kept her eyes low, seeming studious and guilty. There was serious news: Nedra lost her job today, on her day off.

“Actually, it’s funny the way it happened,” said Nedra.

She’d gone to the office to pick up her check and while she was there asked her boss for more hours. But you don’t make your regular hours, her boss had pointed out. “What could I say,” Nedra said now. “I had to agree.”

“Did you? Have to?” A mountain began to rise up inside Syreeta, but seeing that the children were watching, she mashed it back down to regular earth.

“She didn’t get fired,” said Kelly. “It was more so a mutual decision.”

“More so,” said Syreeta. She could hear her voice rising above the other sounds in the kitchen and checked herself. “Sure.”

Nedra did not reply. She had known her sister for a long time.

The sister mamas spoke on her behalf, saying her job termination was a blessing in disguise because now Nedra could focus on her real passion, her new hair-care line. She had an entire fleet of quality products: Ancient Royal Melanin Kokum Pepper Shampoo, Island Mangosteen Oil, Arabic Putieo Kiss Curl Pudding. All designed to moisturize and miracle-grow your hair beyond its potential. Nedra had it all worked out, down to the Afrocentric labels and jelly jars. However, she felt less confident in the longevity of her business. The plan was to deliver locally so she and her goons could snatch the just delivered packages from front porches and resell them the next day. That was called effective product retention.

“Somebody’s going to whip your ass,” said Syreeta. “And it might be me.”

“Everything is taken care of,” the sister mamas were saying, laying hands too. Ronnie had the bright idea to throw a kickback to make rent in the meantime, so it was like Syreeta didn’t even have to react!

Syreeta’s heart jolted around in stunned frustration. She palmed her wallet and walked out the door, crossing the bridge above the highway. Outside was mist and car exhaust, incredibly green lawns. The air grew colder and colder. Icy bullets rained down. Cars skid into each other, smashing plastic, backing up traffic.

She travelled as far as the gas station on the corner. Catching a glimpse of herself in the glass door was like being squirted in the eyes with lemon juice, she looked so tired. Her feelings popped and sparked through her ears and brain like tiny fireworks of judgement. Good God Almighty, they said. It’s Syreeta Lyles. Who would have thought she’d grow up to become so twisted, left outdoors like an outdoorsy person, dripping funky, acidic rain—and to think, most of her choices were by choice too!

Just then a young man appeared on the other side of the glass door. Irrationally, Syreeta guessed that it was Judah. It was a client: Eric Washington in a nightgown-sized shirt, clutching a tumbler of beet juice. He regarded Syreeta so deeply, the pain and surprise in his eyes landing so heavy on her face, that she stepped back. She nevertheless saw the vertical line between his eyebrows, the neediness there, and before he got to say how glad he was to run into her, she wanted horribly, horribly to run and hide.

Eric could tell she wasn’t excited to see him but said anyway, “I’m so glad to run into you, Miss Syreeta.” Good manners were Eric’s number one strategy. The second was to laugh at his own unexpressed jokes, then give his boyfriend a pitying look for having missed the punchline again. A year of that had worn Kenny out.

“Kenny don’t want you,” said Syreeta. “There’s nothing you can do about it.”

Eric seemed to radiate agonized confusion. But then he remembered that he was a nice guy and recovered quickly. “Did you walk here in the rain?” he said, savoring his own kindness. “Come inside. You want a moon pie or something?”

—

Nighttime fused itself onto the neighborhood, rinsing houses, light poles, and roadways in a rosé petrochemical glow. Syreeta lay in bed, listening to court television and watching the yard across the street, where a low stakes robbery was in motion.

There were three of them, but the pretty one was in charge. Even in the dark, he put on a performance, pimp-walking to the beat of a bad idea. The second, a big boy in green sandals, had failed to talk himself out of the robbery, and the third was just the little brother who hadn’t yet figured out that he didn’t have to be included in everything. Syreeta shook her head. All that conflict of the body and soul for a roscoe with a past, for Granny’s monogrammed silver?

The phone rattled with such aggression. It was Judah calling from the bathroom again. The shower curtain was pulled back, and he was lying in the bathtub, submerged in white foam. There were candles, a grown woman’s husky voice whispered in the background: El amor que ya ha pasado no se debe recordar. With his free hand, Judah twirled a cigar. He looked up at Syreeta, digging in with the praises right away.

“I don’t know anyone like you. You can be in two places at one time. That don’t make you crazy?”

“The world is what makes me crazy,” Syreeta said. “It’ll all be over in a hundred years and nobody even bats an eye.”

“Oh, man. You have a big heart too—which I believe requires a lot of discipline. But because of it you can’t go anywhere or do anything.”

“I went to the convenience store today.” She did not mention that heartbroken Eric Washington had bought her a moon pie.

“That’s what I’m talking about!” Judah said, very excited, nearly manic. What he had was an eye for frailty. His gift was to look into your soul and tell you what’s missing. It was risky to carry on with someone like that. But it was also midnight at the end of the world. The sky twisted and pulled, dragging peace and color. Syreeta figured it was worth the risk, to have a stranger in a bathtub tell her what she was missing.

“Alright, cowboy. Go on and tell me about myself.”

Judah belched silently and apologized, though not disproportionately, with his eyes. “For one, you want your own baby,” he said. “You don’t feel you can comment on other people’s situation unless you have your own.”

“You’re guessing,” said Syreeta.

“You want to lose at least fifteen pounds,” Judah said. “You want somebody to give you flowers and take you to reunion concerts,” he said. “Mostly you want someone to sing with.”

She opened her mouth, but that howling sort of laughter wouldn’t pour out. “You remind me of the magician that used to work at AstroWorld. He would call the card that people chose from the deck. The thing is, they weren’t really choosing. He made them think they were, though. That was the magic.”

Judah nodded, scratching the space between jawbone and ear. “I don’t think I’ve ever been so offended,” he said. “Apologize.”

Down the street a dog was barking obscenities. A light flickered on. The three little delinquents from before went sliding out the window, crashing onto the air-conditioning unit. They were dropping treasure across the lawn, announcing one another’s government names, inadequately jumping fences. That’s when Syreeta could tell that the big boy wasn’t even from here. Just a cousin from Mississippi who’d put a stop to these quarterly visits once his football scholarship came through, and for the first time in his life, he had what they called options.

“This is a waste of time,” Syreeta said. “I thought you was going to tell me the real stuff.”

“I could,” said Judah, and the crepe myrtles outside his window rattled percussively. “But I’d rather not. It’s better if you find out on your own.”

“I never will,” Syreeta said. “Isn’t that why you’re calling, to tell me?”

She listened to Judah take a deep, staticky breath. “Okay. You don’t really love your sister, although you’ve been trying all your life. With your parents, it’s guilt and obligation, which can feel lovely. But only love is love.”

“So?” Syreeta said softly, drawing her knees into her chest. “Nobody loves their baby sister.”

Judah laughed gothically, wagging his cigar. “You do this thing when you get uncomfortable. You start looking for weakness in other people. It’s deeper than snobbery, I think. You try to make room for yourself. And then you put on your parochial school voice.”

Syreeta was quiet. She sank into the sheets and closed her eyes, listening to the sound of her own heartbeats. She felt as if her body were beginning to melt. Her hair, her ears, her fingertips, her mind.

The feeling spread like soundwaves. “Go on,” she said.

“You pity everyone in this world,” said Judah, “but love is out of the question. Maybe you think you’re protecting yourself. Maybe you think you’re weak. What you don’t know is that you have to be the strongest one to be Syreeta.”

“Oh, I’m a strong black woman.”

“I’m not mocking you,” Judah said patiently. “I’m describing you. You’re one of the world’s great wonders, girl.”

“The world is sick.”

Judah shrugged and leaned into a bank of iridescent foam. “Might get worse too.”

“That’s pretty good,” said Syreeta. “Listen, brother. I’m sorry to tell you this, but you ain’t got the second sight.”

Giving her the corner of his eye, Judah took a long drag from his cigar, and then he shrugged, watching smokey donuts and then jellyfish take flight. “I’ll have to pay you back in some way,” he said. “For wasting your time.”

The rain picked up and storm winds began to lash at the bedroom window. Syreeta bit the inside of her mouth. “Why don’t you come over tomorrow? My sister is having a party.”

“Yeah, I’d planned on stopping by. I read about it on the computer.”

She turned to Nedra’s page where, sure enough, there was a poster advertising the party, done up in the style of Ernie Barnes. Nedra had also posted a disclaimer about her hair products: Clutched Coils Hair Care is not responsible for lost or stolen packages confirmed to be delivered to the address entered for an order. Upon inquiry, Clutched Coils Hair Care will confirm delivery to the address provided, date of delivery, tracking information, and shipping carrier information for the customer to investigate.

When she turned back, Judah was already looking at her, and it gave her a high-dive feeling. He looked her so deep in the face that she tried to reconfigure her features so that they conveyed tranquility and sex appeal.

“I see what you’re thinking,” Syreeta said quickly. “And I know how I look to you.”

“Why don’t you ask me? Ask me for once.”

Syreeta squared her shoulders. “How do I look?”

“Like a planetary beauty. But also, like a snob. Don’t feel bad if you can’t get over yourself. Nobody does.”

To impress her he put on some unreleased Alice Hailey, something that made all that pain and remorse nearly make sense. In the next moment, they were harmonizing with the hook, sounding pretty good together, as though they’d had some musical training. Then they listened as Hailey hit notes nobody could touch without having their heart obliterated. When the song was over, they sighed at the same time. Syreeta felt her heart pull and release.

“How’d you get that record anyway?”

“You the psychic,” Judah was pleased to say. “You tell me.”

Syreeta reached for the remote, muting the television. “It was a gift,” she said.

Selena Anderson is a writer from Texas. Her stories have appeared in Fence, BOMB, Conjunctions, The Baffler, Oxford American, and The Best American Short Stories 2020. She is the recipient of a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award, The Henfield/TransAtlantic Prize, and The Texas Emerging Star Award. She is working on a novel.

During Black History Month, you can purchase a copy of ASF Issue 72, in which Anderson’s story first appeared, for 25% off the cover price in our online store.