In December the Omicron COVID-19 strain was rapidly rising. Colleges and universities had to plan for the upcoming month. How should they react?

In that same December I and some friends started tracking those plans with an eye towards those moving most or all classes online, which I’ve previously dubbed “a toggle term.” Our open and collective spreadsheet ran continuously, with people adding data and updating its accounts. Today I’d like to summarize what we learned by looking at how two national higher education systems, those in Canada and the United States, responded.

One caveat: our data is provisional. We’re going on what people volunteered online. No institution backed this effort nor contributed their research. The spreadsheet probably missed some cases. The data below are conservative, most likely underestimates.

Today, nearly at the end of January, it looks like roughly 160 colleges and universities in North America moved classes online for part or all of that month. About 40 of those campuses are in Canada, while around 120 in the United States. I don’t know if any Mexican campuses followed suit; no data hit the sheet.

You can see some geographic differences at play. Note, for example, the relative lack of campuses online in the American southeast and upper midwest/high plains areas.

For Canada, that’s 40 campuses out of around 436 total, or circa 10% of the nation’s higher education institutions. (source). In the United States the proportion is lower, with 120 out of 4,000 yielding just 3%.

If these numbers are even roughly correct, they tell us that most of Canadian institutions and especially those in the United States decided that the Omicron wave was not a sufficient danger to shift classes online as we did in spring 2020. Other decision-makers surely played key roles here, including local, state/provincial, and national governments, plus funders and members of a given campus’ community.

The steps each campus took to mitigate on-site infections varied. A scan of Inside Higher Ed notices or a glance at the Eduvation listing show a range of strategies: vaccines mandated or recommended, boosters required or encouraged, masking optional/required/a good idea, social distancing, etc. Some delayed the start of spring classes.

How effective were these measures? Did they prevent the spread of COVID-19? How many academics were sickened, injured, or killed? How many off-campus cases occurred as a result of viruses spread by faculty, students, or staff? Did our January 2022 decisions worsen the pandemic, or have any impact at all?

Individual institutions can assess their own cases, and some will do so publicly. But as a sector, sadly, we have no idea in the United States. As I’ve written earlier, data gathering is a mess. Each campus can publish different content on their dashboards, different data, formats, timing, etc. Some can stop updating one or just not offer a dashboard at all. No third party is doing this kind of fine-grained and massive data gathering. Perhaps moving classes online saved some people from debilitation or death. Maybe this toggle term was superfluous. We really can’t tell.

I hope Canada does better. They’ve taken the pandemic more seriously than most in the United States so far.

Given this January, then, what’s next? How will campuses plan their February and spring operations?

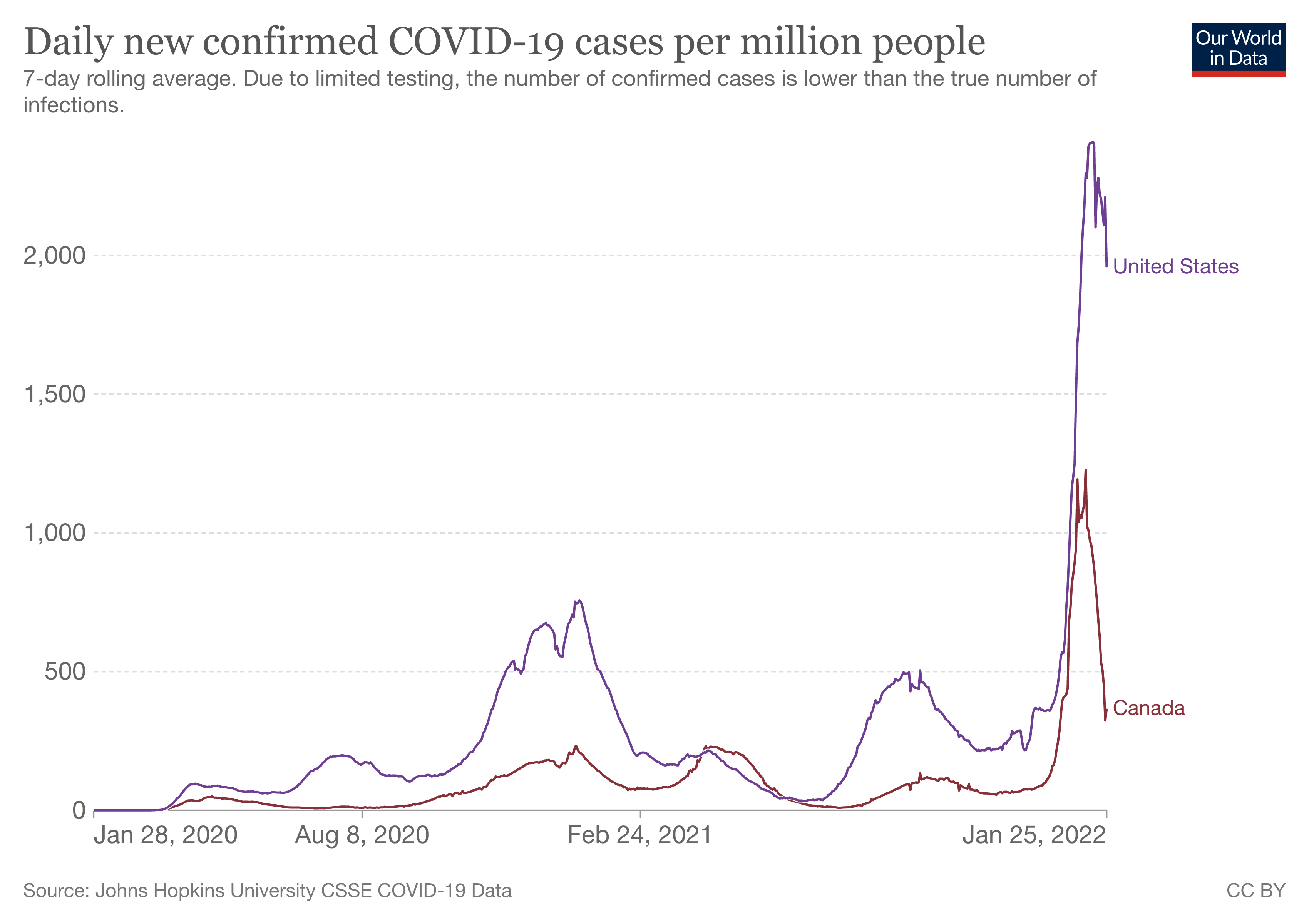

A rising consensus holds that Omicron has peaked. It spread rapidly, infected huge swathes of humanity, and now is running out of new and vulnerable bodies to inhabit. Cases are starting to drop. Our World In Data makes the trend quite clear in terms of infections:

Hospitalizations, a lagging indicator, rose seriously over the past month:

Perhaps American hospitalization has peaked. Or, given the timeline, both nations will see their numbers decline shortly.

Deaths, lagging further still, similarly rose over the past month:

Hopefully that downturn in Canadian deaths represents a serious downward slope.

My intuition is that higher ed wants badly to move on and that Omicron’s peaking – if that’s what we’re experiencing – will translate that desire to planning. We should expect fewer toggle terms starting next month, absent local conditions.

However, COVID continues to mutate and this could change up such plans. Already an Omicron spinoff, BA.2, has appeared. The persistence of vaccination refusal in the developed world and vaccine access in developing nations means there are plenty of unprotected bodies for COVID to inhabit and develop within. We may well see a Pi, Rho, etc. variant as dangerous as, or worse than, Omicron and Delta appear. In which case colleges and universities return to the toggle term option once more.

I suspect that if a Rho wave rises and pushes hospitalizations, long COVID, and deaths up once more, most colleges and universities will prefer in-person operations, at least for classes.

Let me close on a personal note. This past month I have been teaching one class, a Georgetown University graduate seminar on education and technology. We have met online, as per campus directives. Tomorrow’s live class will take place on Zoom. The week after, we shift to the in-person experience. I’m excited to see my students in person. I’m happy to have access to Georgetown’s great resources: a fine classroom, the lovely library, a splendid media center. I look forward to seeing colleagues. I know Georgetown has done a serious job of requiring vaccines, boosting, and masks. At the same time I worry about my trip into campus on the Metro. I’m simply anxious about being around other people.

The difference might not be so stark. Students will have the option of attending virtually, so the seminar will be in HyFlex mode. Which they are very well positioned to take advantage of and to study, given the seminar’s topic.

How was your January academic experience? What do you anticipate for the rest of this unusual spring? And what data should we add?

(thanks to Jody Greene and the many people who contributed to the spreadsheet)