Author and Page information

- This page: https://www.globalissues.org/article/35/foreign-aid-development-assistance.

- To print all information (e.g. expanded side notes, shows alternative links), use the print version:

Foreign aid or (development assistance) is often regarded as being too much, or wasted on corrupt recipient governments despite any good intentions from donor countries. In reality, both the quantity and quality of aid have been poor and donor nations have not been held to account.

There are numerous forms of aid, from humanitarian emergency assistance, to food aid, military assistance, etc. Development aid has long been recognized as crucial to help poor developing nations grow out of poverty.

In 1970, the world’s rich countries agreed to give 0.7% of their GNI (Gross National Income) as official international development aid, annually. Since that time, despite billions given each year, rich nations have rarely met their actual promised targets. For example, the US is often the largest donor in dollar terms, but ranks amongst the lowest in terms of meeting the stated 0.7% target.

Furthermore, aid has often come with a price of its own for the developing nations:

- Aid is often wasted on conditions that the recipient must use overpriced goods and services from donor countries

- Most aid does not actually go to the poorest who would need it the most

- Aid amounts are dwarfed by rich country protectionism that denies market access for poor country products, while rich nations use aid as a lever to open poor country markets to their products

- Large projects or massive grand strategies often fail to help the vulnerable as money can often be embezzled away.

This article explores who has benefited most from this aid, the recipients or the donors.

On this page:

- Governments Cutting Back on Promised Responsibilities

- Foreign Aid Numbers in Charts and Graphs

- Are numbers the only issue?

- Aid as a foreign policy tool to aid the donor not the recipient

- Aid Amounts Dwarfed by Effects of First World Subsidies, Third World Debt, Unequal Trade, etc

- But aid could be beneficial

- Trade and Aid

- Improving Economic Infrastructure

- Use aid to Empower, not to Prescribe

- Rich donor countries and aid bureaucracies are not accountable

- Democracy-building is fundamental, but harder in many developing countries

- Failed foreign aid and continued poverty: well-intentioned mistakes, calculated geopolitics, or a mix?

Governments Cutting Back on Promised Responsibilities

Trade, not aid

is regarded as an important part of development promoted by some nations. But in the context of international obligations, it is also criticized by many as an excuse for rich countries to cut back aid that has been agreed and promised at the United Nations.

Rich Nations Agreed at UN to 0.7% of GNP To Aid

The aid is to come from the roughly 22 members of the OECD, known as the Development Assistance Committee (DAC). [Note that terminology is changing. GNP, which the OECD used up to 2000 is now replaced with the similar GNI, Gross National Income which includes a terms of trade adjustment. Some quoted articles and older parts of this site may still use GNP or GDP.]

ODA is basically aid from the governments of the wealthy nations, but doesn’t include private contributions or private capital flows and investments. The main objective of ODA is to promote development. It is therefore a kind of measure on the priorities that governments themselves put on such matters. (Whether that necessarily reflects their citizen’s wishes and priorities is a different matter!)

Almost all rich nations fail this obligation

Even though these targets and agendas have been set, year after year almost all rich nations have constantly failed to reach their agreed obligations of the 0.7% target. Instead of 0.7%, the amount of aid has been around 0.2 to 0.4%, some $150 billion short each year.

Some donate many dollars, but are low on GNI percent

Some interesting observations can be made about the amount of aid. For example:

- USA’s aid, in terms of percentage of their GNP has almost always been lower than any other industrialized nation in the world, though paradoxically since 2000, their dollar amount has been the highest.

- Between 1992 and 2000, Japan had been the largest donor of aid, in terms of raw dollars. From 2001 the United States claimed that position, a year that also saw Japan’s amount of aid drop by nearly 4 billion dollars.

Aid increasing since 2001 but still way below obligations

Throughout the 1990s, ODA declined from a high

of 0.33% of total DAC aid in 1990 to a low of 0.22% in 1997. 2001 onwards has seen a trend of increased aid. Side NoteThe UN noted the irony that the decline in aid came at a time where conditions were improving for its greater effectiveness . According to the World Bank, overall, the official development assistance worldwide had been decreasing about 20% since 1990.

Between 2001 and 2004, there was a continual increase in aid, but much of it due to geo-strategic concerns of the donor, such as fighting terrorism. Increases in 2005 were largely due to enormous debt relief for Iraq, Nigeria, plus some other one-off large items.

(As will be detailed further below, aid has typically followed donor’s interests, not necessarily the recipients, and as such the poorest have not always been the focus for such aid. Furthermore, the numbers, as low as they are, are actually more flattering to donor nations than they should be: the original definition of aid was never supposed to include debt relief or humanitarian emergency assistance, but instead was meant for development purposes. This is discussed further below, too.)

Foreign Aid Numbers in Charts and Graphs

And who gets what?

Aid money is actually way below what has been promised

Side note on private contributions

As an aside, it should be emphasized that the above figures are comparing government spending. Such spending has been agreed at international level and is spread over a number of priorities.

Individual/private donations may be targeted in many ways. However, even though the charts above do show US aid to be poor (in percentage terms) compared to the rest, the generosity of the American people is far more impressive than their government. Private aid/donation typically through the charity of individual people and organizations can be weighted to certain interests and areas. Nonetheless, it is interesting to note for example, based on estimates in 2002, Americans privately gave at least $34 billion overseas — more than twice the US official foreign aid of $15 billion at that time:

- International giving by US foundations: $1.5 billion per year

- Charitable giving by US businesses: $2.8 billion annually

- American NGOs: $6.6 billion in grants, goods and volunteers.

- Religious overseas ministries: $3.4 billion, including health care, literacy training, relief and development.

- US colleges scholarships to foreign students: $1.3 billion

- Personal remittances from the US to developing countries: $18 billion in 2000

- Source: Dr. Carol Adelman, Aid and Comfort, Tech Central Station, 21 August 2002.

Although Adelman admitted that there are no complete figures for international private giving

she still claimed that Americans are clearly the most generous on earth in public—but especially in private—giving

. While her assertions should be taken with caution, the numbers are high.

Ranking the Rich based on Commitment to Development

Private donations and philanthropy

Government aid, while fraught with problems (discussed below), reflects foreign policy objectives of the donor government in power, which can differ from the generosity of the people of that nation. It can also be less specialized than private contributions and targets are internationally agreed to be measurable.

Private donations, especially large philanthropic donations and business givings, can be subject to political/ideological or economic end-goals and/or subject to special interest. A vivid example of this is in health issues around the world. Amazingly large donations by foundations such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation are impressive, but the underlying causes of the problems are not addressed, which require political solutions. As Rajshri Dasgupta comments:

Private charity is an act of privilege, it can never be a viable alternative to State obligations,said Dr James Obrinski, of the organisation Medicins sans Frontier, in Dhaka recently at the People’s Health Assembly (see Himal, February 2001). In a nutshell, industry and private donations are feel-good, short-term interventions and no substitute for the vastly larger, and essentially political, task of bringing health care to more than a billion poor people.

As another example, Bill Gates announced in November 2002 a massive donation of $100 million to India over ten years to fight AIDS there. It was big news and very welcome by many. Yet, at the same time he made that donation, he was making another larger donation—over $400 million, over three years—to increase support for Microsoft’s software development suite of applications and its platform, in competition with Linux and other rivals. Thomas Green, in a somewhat cynical article, questions who really benefits, saying And being a monster MS [Microsoft] shareholder himself, a

(Emphasis is original.)Big Win

in India will enrich him [Bill Gates] personally, perhaps well in excess of the $100 million he’s donating to the AIDS problem. Makes you wonder who the real beneficiary of charity is here.

India has potentially one tenth of the world’s software developers, so capturing the market there of software development platforms is seen as crucial. This is just one amongst many examples of what appears extremely welcome philanthropy and charity also having other motives. It might be seen as horrible to criticize such charity, especially on a crucial issue such as AIDS, but that is not the issue. The concern is that while it is welcome that this charity is being provided, at a systemic level, such charity is unsustainable and shows ulterior motives. Would Bill Gates have donated that much had there not been additional interests for the company that he had founded?

In addition, as award-winning investigative reporter and author Greg Palast also notes, the World Trade Organization’s Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), the rule which helps Gates rule, also bars African governments from buying AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis medicine at cheap market prices.

He also adds that it is killing more people than the philanthropy saving. What Palast is hinting towards is the unequal rules of trade and economics that are part of the world system, that has contributed to countries such as most in Africa being unable to address the scourge of AIDS and other problems, even when they want to. See for example, the sections on free trade, poverty and corporations on this web site for more.

The LA Times has also found that the Gates Foundation has been investing in questionable companies that are often involved in environmental pollution, even child labor, and more.

In addition to private contributions, when it comes to government aid, these concerns can multiply as it may affect the economic and political direction of an entire nation if such government aid is also tied into political objectives that benefit the donor.

Are numbers the only issue?

As we will see further below, some aid has indeed been quite damaging for the recipient, while at the same time being beneficial for the donor.

Aid is Actually Hampering Development

See also, for example, the well-regarded Reality of Aid project for more on the reality and rhetoric of aid. This project looks at what various nations have donated, and how and where it has been spent, etc.

Private flows often do not help the poorest

While ODA’s prime purpose is to promote development, private flows are often substantially larger than ODA. During economic booms, more investment is observed in rapidly emerging economies, for example. But this does not necessarily mean the poorest nations get such investment.

During the boom of the mid-2000s before the global financial crisis sub-Saharan Africa did not attract as much investment from the rich nations, for example (though when China decided to invest in Africa, rich nations looked on this suspiciously fearing exploitation, almost ignoring their own decades of exploitation of the continent. China’s interest is no-doubt motivated by self-interest, and time will have to tell whether there is indeed exploitation going on, or if African nations will be able to demand fair conditions or not).

As private flows to developing countries from multinational companies and investment funds reflect the interests of investors, the importance of Overseas Development Assistance cannot be ignored.

Furthermore, (and detailed below) these total flows are less than the subsidies many of the rich nations give to some of their industries, such as agriculture, which has a direct impact on the poor nations (due to flooding the market with—or dumping—excess products, protecting their own markets from the products of the poor countries, etc.)

In addition, a lot of other inter-related issues, such as geopolitics, international economics, etc all tie into aid, its effectiveness and its purpose. Africa is often highlighted as an area receiving more aid, or in need of more of it, yet, in recent years, it has seen less aid and less investment etc, all the while being subjected to international policies and agreements that have been detrimental to many African people.

For the June 2002 G8 summit, a briefing was prepared by Action for Southern Africa and the World Development Movement, looking at the wider issue of economic and political problems:

It is undeniable that there has been poor governance, corruption and mismanagement in Africa. However, the briefing reveals the context—the legacy of colonialism, the support of the G8 for repressive regimes in the Cold War, the creation of the debt trap, the massive failure of Structural Adjustment Programmes imposed by the IMF and World Bank and the deeply unfair rules on international trade. The role of the G8 in creating the conditions for Africa’s crisis cannot be denied. Its overriding responsibility must be to put its own house in order, and to end the unjust policies that are inhibiting Africa’s development.

As the above briefing is titled, a common theme on these issues (around the world) has been to blame the victim

. The above briefing also highlights some common myths

often used to highlight such aspects, including (and quoting):

- Africa has received increasing amounts of aid over the years—in fact, aid to Sub-Saharan Africa fell by 48% over the 1990s

- Africa needs to integrate more into the global economy—in fact, trade accounts for larger proportion of Africa’s income than of the G8

- Economic reform will generate new foreign investment—in fact, investment to Africa has fallen since they opened up their economies

- Bad governance has caused Africa’s poverty—in fact, according to the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), economic conditions imposed by the IMF and the World Bank were the dominant influence on economic policy in the two decades to 2000, a period in which Africa’s income per head fell by 10% and income of the poorest 20% of people fell by 2% per year

The quantity issue is an input into the aid process. The quality is about the output. We see from the above then, that the quantity of aid has not been as much as it should be. But what about the quality of the aid?

Aid appears to have established as a priority the importance of influencing domestic policy in the recipient countries

As shown throughout this web site (and hundreds of others) one of the root causes of poverty lies in the powerful nations that have formulated most of the trade and aid policies today, which are more to do with maintaining dependency on industrialized nations, providing sources of cheap labor and cheaper goods for populations back home and increasing personal wealth, and maintaining power over others in various ways. As mentioned in the structural adjustment section, so-called lending and development schemes have done little to help poorer nations progress.

The US, for example, has also held back dues to the United Nations, which is the largest body trying to provide assistance in such a variety of ways to the developing countries. Former US President Jimmy Carter describes the US as stingy

:

While the US provided large amounts of military aid to countries deemed strategically important, others noted that the US ranked low among developed nations in the amount of humanitarian aid it provided poorer countries.

We are the stingiest nation of all,former President Jimmy Carter said recently in an address at Principia College in Elsah, Ill.

Evan Osbourne, writing for the Cato Institute, also questioning the effectiveness of foreign aid and noted the interests of a number of other donor countries, as well as the U.S., in their aid strategies in past years. For example:

- The US has directed aid to regions where it has concerns related to its national security, e.g. Middle East, and in Cold War times in particular, Central America and the Caribbean;

- Sweden has targetted aid to

progressive societies

; - France has sought to promote maintenance or preserve and spread of French culture, language, and influence, especially in West Africa, while disproportionately giving aid to those that have extensive commercial ties with France;

- Japan has also heavily skewed aid towards those in East Asia with extensive commercial ties together with conditions of Japanese purchases;

Osbourne also added that domestic pressure groups (corporate lobby groups, etc) have also proven quite adept at steering aid to their favored recipients.

And so, If aid is not particularly given with the intention to foster economic growth, it is perhaps not surprising that it does not achieve it.

Aid Money Often Tied to Various Restrictive Conditions

In their 2000 report looking back at the previous year, the Reality of Aid 2000 (Earthscan Publications, 2000, p.81), reported in their US section that 71.6% of its bilateral aid commitments were tied to the purchase of goods and services from the US.

That is, where the US did give aid, it was most often tied to foreign policy objectives that would help the US.

Leading up to the UN Conference on Financing for Development in Monterrey, Mexico in March 2002, the Bush administration promised a nearly $10 billion fund over three years followed by a permanent increase of $5 billion a year thereafter. The EU also offered some $5 billion increase over a similar time period.

While these increases have been welcome, these targets are still below the 0.7% promised at the Earth summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. The World Bank have also leveled some criticism of past policies:

Commenting on the latest US pledge [of $10 billion], Julian Borger and Charlotte Denny of the Guardian (UK) say Washington is desperate to deflect attention in Monterrey from the size of its aid budget. But for more generous donors, says the story, Washington’s conversion to the cause of effective aid spending is hard to swallow. Among the big donors, the US has the worst record for spending its aid budget on itself—70 percent of its aid is spent on US goods and services. And more than half is spent in middle income countries in the Middle East. Only $3bn a year goes to South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

In addition, promises of more money were tied to more conditions, which for many developing countries is another barrier to real development, as the conditions are sometimes favorable to the donor, not necessarily the recipient. Delhi-based Centre for Science and Environment commented on the US conditional pledge of more money that:

Thus, status quo in world relations is maintained. Rich countries like the US continue to have a financial lever to dictate what good governance means and to pry open markets of developing countries for multinational corporations. Developing countries have no such handle for Northern markets, even in sectors like agriculture and textiles, where they have an advantage but continue to face trade barriers and subsidies. The estimated annual cost of Northern trade barriers to Southern economies is over US $100 billion, much more than what developing countries receive in aid.

Another aspect of aid tying into interests of donors is exemplified with climate change negotiations. Powerful nations such as the United States have been vocally against the Kyoto Protocol on climate change. Unlike smaller countries, they have been able to exert their influence on other countries to push for bilateral agreements conditioned with aid, in a way that some would describe as a bribe. Center for Science and Environment for example criticizes such politics:

It is easy to be taken in with promises of bilateral aid, and make seemingly innocuous commitments in bilateral agreements. There is far too much at stake here [with climate change]. To further their interests, smaller, poorer countries don’t have aid to bribe and trade muscle to threaten countries.

This use of strength in political and economic arenas is nothing new. Powerful nations have always managed to exert their influence in various arenas. During the Gulf War in 1991 for example, many that ended up in the allied coalition were promised various concessions behind the scenes (what the media described as diplomacy

). For example, Russia was offered massive IMF money. Even now, with the issue of the International Criminal Court, which the US is also opposed to, it has been pressuring other nations on an individual basis to not sign, or provide concessions. In that context, aid is often tied to political objectives and it can be difficult to sometimes see when it is not so.

But some types of conditions attached to aid can also be ideologically driven. For example, quoted further above by the New York Times, James Wolfensohn, the World Bank president noted how European and American farm subsidies are crippling Africa’s chance to export its way out of poverty.

While this criticism comes from many perspectives, Wolfensohn’s note on export also suggests that some forms of development assistance may be on the condition that nations reform their economies to certain ideological positions. Structural Adjustment has been one of these main policies as part of this neoliberal ideology, to promote export-oriented development in a rapidly opened economy. Yet, this has been one of the most disastrous policies in the past two decades, which has increased poverty. Even the IMF and World Bank have hinted from time to time that such policies are not working. People can understand how tying aid on condition of improving human rights, or democracy might be appealing, but when tied to economic ideology, which is not always proven, or not always following the one size fits all

model, the ability (and accountability) of decisions that governments would have to pursue policies they believe will help their own people are reduced.

More Money Is Transferred From Poor Countries to Rich, Than From Rich To Poor

For the OECD countries to meet their obligations for aid to the poorer countries is not an economic problem. It is a political one. This can be seen in the context of other spending. For example,

- The US recently increased its military budget by some $100 billion dollars alone

- Europe subsidizes its agriculture to the tune of some $35-40 billion per year, even while it demands other nations to liberalize their markets to foreign competition.

- The US also introduced a $190 billion dollar subsidy to its farms through the US Farm Bill, also criticized as a protectionist measure.

- While aid amounts to around $70 to 100 billion per year, the poor countries pay some $200 billion to the rich each year.

- There are many more (some mentioned below too).

In effect then, there is more aid to the rich than to the poor.

While the amount of aid from some countries such as the US might look very generous in sheer dollar terms (ignoring the percentage issue for the moment), the World Bank also pointed out that at the World Economic Forum in New York, February 2002, [US Senator Patrick] Leahy noted that two-thirds of US government aid goes to only two countries: Israel and Egypt. Much of the remaining third is used to promote US exports or to fight a war against drugs that could only be won by tackling drug abuse in the United States.

In October 2003, at a United Nations conference, UN Secretary General Kofi Annan noted that

developing countries made the sixth consecutive and largest ever transfer of funds to

other countriesin 2002, a sum totallingalmost $200 billion.

Funds should be moving from developed countries to developing countries, but these numbers tell us the opposite is happening…. Funds that should be promoting investment and growth in developing countries, or building schools and hospitals, or supporting other steps towards the Millennium Development Goals, are, instead, being transferred abroad.

And as Saradha Lyer, of Malaysia-based Third World Network notes, instead of promoting investment in health, education, and infrastructure development in the third world, this money has been channelled to the North, either because of debt servicing arrangements, asymmetries and imbalances in the trade system or because of inappropriate liberalization and privatization measures imposed upon them by the international financial and trading system.

This transfer from the poorer nations to the rich ones makes even the recent increase in ODA seem little in comparison.

Aid Amounts Dwarfed by Effects of First World Subsidies, Third World Debt, Unequal Trade, etc

Combining the above mentioned reversal of flows with the subsidies and other distorting mechanisms, this all amounts to a lot of money being transferred to the richer countries (also known as the global North), compared to the total aid amounts that goes to the poor (or South).

As well as having a direct impact on poorer nations, it also affects smaller farmers in rich nations. For example, Oxfam, criticizing EU double standards, highlights the following:

Latin America is the worst-affected region, losing $4bn annually from EU farm policies. EU support to agriculture is equivalent to double the combined aid budgets of the European Commission and all 15 member states. Half the spending goes to the biggest 17 per cent of farm enterprises, belying the manufactured myth that the CAP [Common Agriculture Policy] is all about keeping small farmers in jobs.

The double standards that Oxfam mentions above, and that countless others have highlighted has a huge impact on poor countries, who are pressured to follow liberalization and reducing government interference

while rich nations are able to subsidize some of their industries. Poor countries consequently have an even tougher time competing. IPS captures this well:

On the one hand, OECD countries such as the US, Germany or France continue through the ECAs [export credit agencies] to subsidise exports with taxpayers’ money, often in detriment to the competitiveness of the poorest countries of the world,says [NGO Environment Defence representative, Aaron] Goldzimmer.On the other hand, the official development assistance which is one way to support the countries of the South to find a sustainable path to development and progress is being reduced.…

Government subsidies mean considerable cost reduction for major companies and amount to around 10 per cent of annual world trade. In the year 2000, subsidies through ECAs added up to 64 billion dollars of exports from industrialised countries, well above the official development assistance granted last year of 51.4 billion dollars.

As well as agriculture, textiles and clothing is another mainstay of many poor countries. But, as with agriculture, the wealthier countries have long held up barriers to prevent being out-competed by poorer country products. This has been achieved through things like subsidies and various agreements

. The impact to the poor has been far-reaching, as Friends of the Earth highlights:

Despite the obvious importance of the textile and clothing sectors in terms of development opportunities, the North has consistently and systematically repressed developing country production to protect its own domestic clothing industries.

Since the 1970s the textile and clothing trade has been controlled through the Multi-Fibre Arrangement (MFA) which sets bilateral quotas between importing and exporting countries. This was supposedly to protect the clothing industries of the industrialised world while they adapted to competition from developing countries. While there are cases where such protection may be warranted, especially for transitionary periods, the MFA has been in place since 1974 and has been extended five times. According to Oxfam, the MFA is,

…the most significant..[non tariff barrier to trade]..which has faced the world’s poorest countries for over 20 years.Although the MFA has been replaced by the Agreement on Textiles and Clothing (ATC) which phases out support over a further ten year period—albeit through a process which in itself is highly inequitable—developing countries are still suffering the consequences. The total cost to developing countries of restrictions on textile imports into the developed world has been estimated to be some $50 billion a year. This is more or less equivalent to the total amount of annual development assistance provided by Northern governments to the Third World.

January 24, 2001

There is often much talk of trade rather than aid, of development, of opening markets etc. But, when at the same time some of the important markets of the US, EU and Japan appear to be no-go areas for the poorer nations, then such talk has been criticized by some as being hollow. The New York Times is worth quoting at length:

Our compassion [at the 2002 G8 Summit talking of the desire to help Africa] may be well meant, but it is also hypocritical. The US, Europe and Japan spend $350 billion each year on agricultural subsidies (seven times as much as global aid to poor countries), and this money creates gluts that lower commodity prices and erode the living standard of the world’s poorest people.

These subsidies are crippling Africa’s chance to export its way out of poverty,said James Wolfensohn, the World Bank president, in a speech last month.Mark Malloch Brown, the head of the United Nations Development Program, estimates that these farm subsidies cost poor countries about $50 billion a year in lost agricultural exports. By coincidence, that’s about the same as the total of rich countries’ aid to poor countries, so we take back with our left hand every cent we give with our right.

It’s holding down the prosperity of very poor people in Africa and elsewhere for very narrow, selfish interests of their own,Mr. Malloch Brown says of the rich world’s agricultural policy.It also seems a tad hypocritical of us to complain about governance in third-world countries when we allow tiny groups of farmers to hijack billion of dollars out of our taxes.

In fact, J. Brian Atwood, stepped down in 1999 as head of the US foreign aid agency, USAID. He was very critical of US policies, and vented his frustration that despite many well-publicized trade missions, we saw virtually no increase of trade with the poorest nations. These nations could not engage in trade because they could not afford to buy anything.

(Quoted from a speech that he delivered to the Overseas Development Council.)

As Jean-Bertrand Arisitde also points out, there is also a boomerang effect of loans as large portions of aid money is tied to purchases of goods and trade with the donor:

Many in the first world imagine the amount of money spent on aid to developing countries is massive. In fact, it amounts to only 0.3% of GNP of the industrialized nations. In 1995, the director of the US aid agency defended his agency by testifying to his congress that 84 cents of every dollar of aid goes back into the US economy in goods and services purchased. For every dollar the United States puts into the World Bank, an estimated $2 actually goes into the US economy in goods and services. Meanwhile, in 1995, severely indebted low-income countries paid one billion dollars more in debt and interest to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) than they received from it. For the 46 countries of Subsaharan Africa, foreign debt service was four times their combined governmental health and education budgets in 1996. So, we find that aid does not aid.

In other words, often aid does not aid the recipient, it aids the donor. For the US in the above example, its aid agency has been a foreign policy tool to enhance its own interests, successfully.

And then there has been the disastrous food aid policies, which is another example of providing aid but using that aid as an arm of foreign policy objectives. It has helped their corporations and large farmers at a huge cost to developing countries, and has seen an increase in hunger, not reduction. For more details, see the entire section on this site that discusses this, in the Poverty and Food Dumping part of this web site.

For the world’s hungry, however, the problem isn’t the stinginess of our aid. When our levels of assistance last boomed, under Ronald Reagan in the mid-1980s, the emphasis was hardly on eliminating hunger. In 1985, Secretary of State George Shultz stated flatly that

our foreign assistance programs are vital to the achievement of our foreign policy goals.But Shultz’s statement shouldn’t surprise us. Every country’s foreign aid is a tool of foreign policy. Whether that aid benefits the hungry is determined by the motives and goals of that policy—by how a government defines the national interest.

The above quote from the book World Hunger is from Chapter 10, which is also reproduced in full on this web site. It also has more facts and stats on US aid and foreign policy objectives, etc.

As an aside, it is interesting to note the disparities between what the world spends on military, compared to other international obligations and commitments. Most wealthy nations spend far more on military than development, for example. The United Nations, which gets its monies from member nations, spends about $10 billion—or about 3% of what just the US alone spends on its military. It is facing a financial crisis as countries such as the US want to reduce their burden of the costs—which comparatively is quite low anyway—and have tried to withhold payments or continued according to various additional conditions.

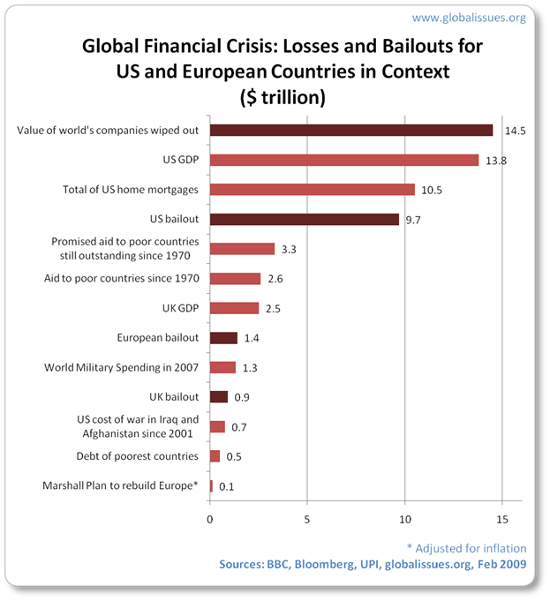

And with the recent financial crisis, clearly the act of getting resources together is not the issue, as far more has been made available in just a few short months than an entire 4 decades of aid:

But, as the quote above highlights as well, as well as the amount of aid, the quality of aid is important. (And the above highlights that the quality has not been good either.)

But aid could be beneficial

Government aid, from the United States and others, as indicated above can often fall foul of political agendas and interests of donors. At the same time that is not the only aid going to poor countries. The US itself, for example, has a long tradition of encouraging charitable contributions. Indeed, tax laws in the US and various European countries are favorable to such giving as discussed further above. But private funding, philanthropy and other sources of aid can also fall foul of similar or other agendas, as well as issues of concentration on some areas over others, of accountability, and so on. (More on these aspects is introduced on this site’s NGO and Development section.)

Trade and Aid

Oxfam highlights the importance of trade and aid:

Some Northern governments have stressed that

trade not aidshould be the dominant theme at the [March 2002 Monterrey] conference [on Financing for Development]. That approach is disingenuous on two counts. First, rich countries have failed to open their markets to poor countries. Second, increased aid is vital for the world’s poorest countries if they are to grasp the opportunities provided through trade.

In addition to trade not aid

perspectives, the Bush Administration was keen to push for grants rather than loans from the World Bank. Grants being free money appears to be more welcome, though many European nations aren’t as pleased with this option. Furthermore, some commentators point out that the World Bank, being a Bank, shouldn’t give out grants, which would make it compete with other grant-offering institutions such as various other United Nations bodies. Also, there is concern that it may be easier to impose political conditions to the grants. John Taylor, US Undersecretary of the Treasury, in a recent speech in Washington also pointed out that Grants are not free. Grants can be easily be tied to measurable performance or results.

Some comment that perhaps grants may lead to more dependencies as well as some nations may agree to even more conditions regardless of the consequences, in order to get the free money. (More about the issue of grants is discussed by the Bretton Woods Project.)

In discussing trade policies of the US, and EU, in relation to its effects on poor countries, chief researcher of Oxfam, Kevin Watkins, has been very critical, even charging them with hypocrisy for preaching free trade but practicing mercantilism:

Looking beyond agriculture, it is difficult to avoid being struck by the discrepancy between the picture of US trade policy painted by [US Trade Representative, Robert] Zoellick and the realities facing developing countries.

To take one example, much has been made of America’s generosity towards Africa under the Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA). This provides what, on the surface, looks like free market access for a range of textile, garment and footwear products. Scratch the surface and you get a different picture. Under AGOA’s so-called rules-of-origin provisions, the yarn and fabric used to make apparel exports must be made either in the United States or an eligible African country. If they are made in Africa, there is a ceiling of 1.5 per cent on the share of the US market that the products in question can account for. Moreover, the AGOA’s coverage is less than comprehensive. There are some 900 tariff lines not covered, for which average tariffs exceed 11%.

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the benefits accruing to Africa from the AGOA would be some $420m, or five times, greater if the US removed the rules-of-origin restrictions. But these restrictions reflect the realities of mercantilist trade policy. The underlying principle is that you can export to America, provided that the export in question uses American products rather than those of competitors. For a country supposedly leading a crusade for open, non-discriminatory global markets, it’s a curiously anachronistic approach to trade policy.

Watkins lists a number of other areas, besides the AGOA that are beset with problems of hypocrisy, and concludes that nihilism and blind pursuit of US economic and corporate special interest represents an obstacle to the creation of an international trading system capable of extending the benefits of globalisation to the world’s poor.

(See also this site’s section on free trade and globalization, where there is more criticism about northern countries exhibiting mercantilist, or monopoly capitalist principles, rather than free market capitalism, even though that is what is preached to the rest of the world.)

In that context then, and given the problems mentioned further above about agricultural and textiles/clothing subsidies, etc. the current amount of aid given to poor countries doesn’t compare to aid

given to wealthier countries’ corporations and industries and hardly compensates for what is lost.

Both increasing and restructuring aid to truly provide developing countries the tools and means to develop for themselves, for example, would help recipients of aid, not just the donors. Aid is more than just charity and cannot be separated from other issues of politics and economics, which must also be considered.

Improving Economic Infrastructure

Trade not Aid

sounds like decent rhetoric. As the economist Amartya Sen for example says, a lot that can be done at a relatively little cost. Unfortunately, so far, it seems that rhetoric is mostly what it has turned out to be.

In addition, as J.W. Smith further qualifies, rather than giving money that can be squandered away, perhaps the best form of aid would be industry, directly:

Do Not Give the Needy Money: Build Them Industries Instead

With the record of corruption within impoverished countries, people will question giving them money. That can be handled by giving them the industry directly, not the money. To build a balanced economy, provide consumer buying power, and develop arteries of commerce that will absorb the production of these industries, contractors and labor in those countries should be used. Legitimacy and security of contracts is the basis of any sound economy. Engineers know what those costs should be and, if cost overruns start coming in, the contractor who has proven incapable should be replaced—just as any good contract would require…. When provided the industry, as opposed to the money to build industry, those people will have physical capital. The only profits to be made then are in production; there is no development money to intercept and send to a Swiss bank account.

online)

Whether the hope for effective foreign aid will actually turn into reality is harder to know, because of power politics, which has characterized and shaped the world for centuries.

A risk for developing countries that look to aid, at least in their short-term plans to kick-start development (for becoming dependent on aid over the long run seems a dangerous path to follow), is that people of the rich world will see the failures of aid without seeing the detailed reasons why, creating a backlash of donor fatigue, reluctance and cynicism.

Author and Page Information

- Created:

- Last updated: