The second sexual revolution began 30 years ago, on 23 September 1991, with the release of an educational videotape called The Lovers’ Guide. The revolution’s unlikely figureheads were a film producer who had been making how-to videos about gardening and pets and cooking, and a 56-year-old doctor, while their ally was an American former TV and theatre director who had become Britain’s chief film censor.

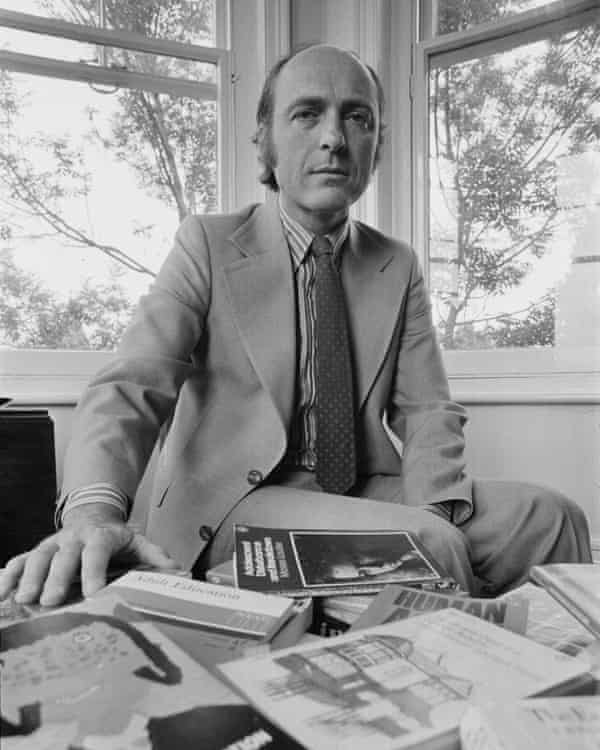

The producer was a man called Robert Page, who had been approached by Virgin – which had recently started making condoms – to make a sexual health film for men that explained how to use one. There were two difficulties with that. The first was that no erect penis had been shown on screen in Britain. The second was that Page had no interest in making a film about penises. The censor – James Ferman, the director of the British Board of Film Classification from 1975 to 1999 – took care of the first issue.

“I was talking to the great James Ferman,” Page says, talking from New York, where he now lives, “and he went, ‘There’s only one law, and it’s called obscenity and it’s that which will deprave and corrupt.’ He said, ‘I see nothing depraving or corrupting in a man pulling a condom on in this era. I think it’s downright sensible.’”

Page brought up the second issue. “I went, ‘You know all these how-to videos? There’s this area of life that we don’t talk about. You wouldn’t let me make one about sex, would you?’ He said, ‘What would you want to show?’ I went, ‘Men and women, with actual intercourse.’” Page wanted to show oral sex. He wanted to show genitals. He wanted to show the things that even films made for sex shops couldn’t show, and he wanted to show them in a film that would get an 18 certificate and be sold as a VHS tape on the high street.

Ferman laid down conditions. The film had to be fronted by a doctor. The script had to be approved by a reputable organisation. There was to be no lingering on the explicit shots. It was not, in short, to be a mucky film, regardless of what its viewers might use it for.

Page wanted Alex Comfort, the author of The Joy of Sex, to be the doctor, but Comfort’s publishers rejected the idea. Instead he turned to Andrew Stanway, another veteran “sexologist”, with a string of books to his name (Stanway did not respond to requests for an interview). “He was a quite tall, wide man, with huge hands,” says Simon Ludgate, who was hired as director. “He had greying, curly, fair hair, a pointy nose and beady eyes. He reminded me of a bad magician with a ‘look into my eyes’ hypnotic stare.”

It’s Stanway who gives the clinical narration – “The clearest sign of male sexual arousal is an erection. Tissue within the penis fills with blood, making it stiffen. As arousal increases, so does heart rate. Breathing quickens and the nostrils flare” – and he both co-wrote the script and helped recruit the film’s stars. Chief among them were Tony and Wendy Duffield, former patients of his, who went on to be the Brad and Angelina of the sex ed video market. They later appeared on Desmond Morris’s The Human Animal making love with tiny cameras inside them to show the processes at work.

The Duffields weren’t the real problem, though. “There were a couple of people, who were supposed to be a couple and weren’t,” Page says. “One of the guys, the one who stands up to masturbate – Marino – was an adult film professional. We didn’t know that, but the press knew right away. I can’t tell you how naive we were. We had no idea. We had never been in this world. We had done very wholesome stuff, so doing this was breaking new ground.”

The press did indeed know right away, and before the film came out the News of the World revealed the fact that The Lovers’ Guide featured porn stars. “It almost sank us,” Ludgate says. “Woolworths at that point said they weren’t going to stock it, and Woolworths at the time were massive. And then WH Smith said they weren’t going to.”

The shops relented in time for release, and The Lovers’ Guide arrived on the high street. Page and Ludgate are insistent that their motives were purely to help couples, though the film’s makers knew the first certified film to feature explicit sex, even with Stanway’s lugubrious voiceover, would fly out of the shops, and not just to people wanting to learn some new positions. And so Page spent more on The Lovers’ Guide – it was shot on film, not tape, with purpose-built sets – than anything he had ever made before.

He says now he thought it might rival the 250,000 copies of a Neighbours tie-in video he had made. In fact, it sold 200,000 copies in its first fortnight, going on to sell 1.3m in the UK alone, and hundreds of thousands more around the world. (“My greatest regret is not taking a percentage,” Ludgate says. “I still kick myself about that.”)

Looking at it now, in a world of Pornhub, YouPorn, PornMD and everything else, The Lovers’ Guide seems almost unbearably innocent. It is sex at its gentlest. Everything is shot in soft focus; candles are everywhere. (Page was insistent the film’s primary market be women, though the soft focus and candles spoke more to male ideas of female sexuality. Nevertheless, 55% of buyers were women.) Couples wander through fields, smiling happily, before retiring to bedrooms and bathrooms for soft and sensual lovemaking (with a voiceover). Nothing from it would now get anywhere near the front page of a porn aggregator site.

“Some of the sex scenes in The Lovers’ Guide were certainly erotic,” Ferman – who died in 2002 – would later say. “But eroticism was never, I think, the primary purpose of the scene. The primary function of the scene was to be helpful to couples in the audience who were trying to improve their own sex life.” He argued that what separated the finished film from pornography was context: “You weren’t looking at two bodies, two strangers on screen having it away. You were actually looking at people who told what sex meant to them, what their relationships meant, what they wanted to do, what they were trying to do. And they were real people. And ordinary people watching felt, ‘They are just like us, and if this is what they do, this is what we can do.’”

Page accepts that not all his audience had education in mind, but takes the view that he was smuggling greens into their meal. “We discussed this with Jim Ferman. They were buying it to get off on it, but actually they’d learn loads of things along the way. If it had been some medical thing with diagrams, who would have bought it?” (Curiously, Ludgate says that’s exactly what Stanway wanted – women with their legs in stirrups while he pointed out the clitoris.) “There were 10,000 or so letters,” Page continues, “saying, ‘We’ve been married x years, we started watching your programme and we were making love on the living room carpet before it had finished. Thank you for saving our marriage.’ And that was fantastic.”

What was crucial was that you could buy The Lovers’ Guide easily. There were only 80 or so licensed sex shops in the UK, selling R18 films – which were not, at that point, as explicit as The Lovers’ Guide. “My family moved to Cornwall in the 1990s,” says Clarissa Smith, editor of the academic journal Porn Studies, “and the nearest sex shops were in Plymouth or Bristol, but you could buy The Lovers’ Guide in WH Smith. The ease of access was definitely really important.”

While it wasn’t pornography, it was revolutionary. Politics has the concept of the Overton window – the range of policies politically acceptable to the mainstream population at a given time – in which the centre of political gravity shifts left and right. One might think of sex, too, as having its own Overton window, and the 90s saw that window shift to allow portrayals of explicit sex, and an explosion in pornography.

There were simple, practical, legal reasons for that. From 1986, the Reagan and Bush administrations in the US had vigorously pursued obscenity prosecutions against pornographic film-makers. Bill Clinton came to power in 1993 promising to follow that agenda; in fact the Clinton administration had virtually no interest in prosecuting pornographers. In 1992, there were 42 prosecutions in the US in which federal obscenity offences were the lead charge; by 1998, there were only six. The result was a boom in porn production, and the rise of mega-studios such as Evil Empire and Vivid Entertainment.

That would have been irrelevant had porn remained the preserve of sex shops. But three things were happening at once. First, escalating traffic loads caused the first wave of free porn sites – often run by college students, and usually consisting of images stolen from professional porn – to fade from business, because they didn’t have the bandwidth to continue. Second, in summer 1994, a man sold a Sting CD to his friend over the internet, described by the New York Times as “the first retail transaction on the internet using a readily available version of a powerful data encryption software designed to guarantee privacy”. E-commerce was born. It wasn’t long before those who lived too far from sex shops, or who couldn’t bring themselves to walk into one, would be able to buy those Evil Empire and Vivid films without leaving their homes: they could visit a site such as Blissbox and have them delivered, in plain packaging, for the same cost as a Hollywood film, rather than the high prices charged by sex shops for something tamer. Third, a dancer and stripper called Danni Ashe noticed how many of her pictures were being traded on Usenet groups, and set up her own website, sparking a rush for porn producers to sell content directly via the internet.

At the same time, the culture was changing. Soft porn mags for women were launching, as was the hugely explicit Black Lace series of novels, also aimed at women, which sold more than 4m copies between its launch in 1993 and its closure in 2009. Margi Clarke’s TV show The Good Sex Guide launched in 1993, and got unheard-of ratings for a late-night show: 13 million viewers. And a new kind of male culture – in which it was assumed and accepted that viewing porn was nothing to be ashamed of – was emerging. Porn was in newsagents, in the “lad mags”, and it was on screen.

By the end of the 1990s, what was officially licensed lagged so far behind what was readily available to anyone with an internet connection and a credit card that change was inevitable. The driver of change, again, was James Ferman. He was convinced the only way to draw people away from violent pornography – his particular bete noire – was to grant R18 certificates to films depicting consensual penetration and allow them to be sold in licensed sex shops. The test case was a film called Makin’ Whoopee, to the outrage of the new home secretary, Jack Straw.

Straw summoned the BBFC’s vice-president, Lord Birkett, to his office and railed at him. “Do you really mean that you are going to allow oral sex and buggery and I don’t know what else?” Birkett later recalled Straw as saying. “That you are actually passing this? You are giving a certificate to it?”

In the face of Straw’s rage, the BBFC withdrew Makin’ Whoopee’s certification, and Straw changed the body’s leadership, with Ferman and Birkett departing. But in his final report for the BBFC, Ferman displayed prescience. “It may well be that in the 21st century, it simply becomes impossible to impose the kind of regulation which the board exists to provide,” he wrote. “After all, what is the point of cutting a gang-rape scene in a British version of a film if that film is accessible down a telephone line from outside British territorial waters? I am probably the last of the old-time regulators.” Ferman may have lost his job, but he won the fight with Straw – for another statutory body, the Video Appeals Committee, simply reversed the BBFC’s decision to back down, and seven porn films were licensed for sale in sex shops. Censorship of pornography had, to all intents and purposes, finished in the UK.

The Lovers’ Guide did not cause the collapse of censorship. It did not lead to YouPorn. That was the internet. But it was the starting point for a decade of change. “I think it was one of those moments in social history where there was a need for change, and we fulfilled the need,” Ludgate says. “I think there was a collective need for change, and curiosity. Since the 60s, the cult of the individual had grown and this was part of that process. It was something people wanted individually that changed a lot of attitudes towards sex. I think it was a massive, seismic shift in attitudes.”

And still it does its work. A few weeks after we talk, Page forwards an email he has just received. “Hi Robert. I just want to give you a VERY, VERY BIG THANK YOU AGAIN. I have bought your complete collection of The Lover’s GUIDE. Your work is impeccable. I began watching them, and all I can say is. You sir are AWESOME. What I have been learning from them is amazing, and I just really wanted to THANK YOU AGAIN!!!!!!!”