In Depression-era Idaho, six-year-old Stephanie McKittrick helps her mother hire a farmhand after her father is injured; by Obren Bokich.

|

| Image generated with OpenAI |

Since the bank took the Clark farm and Joanie moved to California, there weren’t any other girls my age within a mile of our place. And the Shockey twins didn’t count. They weren’t right in the head, and when I told Mama what they were doing when I brought their mother her welcome cake, she said I wasn’t to go there ever again. This is by way of saying when a grownup asked me if I was excited about starting the first grade in the fall, I replied, “Very much so,” because if I hadn’t been about to turn six, I likely wouldn’t have an actual friend for another year.

I know I sound like I’m lonesome and feeling sorry for myself, and on a farm there’s no excuse for that, surrounded by friendly critters doing entertaining things. There’s a canal to swim in when it isn’t full to the top and rolling like The Great Flood, populated by interesting wild things. There are trees to climb, tall pines with branches low enough I could reach one without standing on anything, and some that blossomed with cherries, apples, and pears. My favorite wasn’t for climbing, a black walnut so tall we couldn’t see the top. The green-husked walnuts fell like missiles, then Papa dumped them on the gravel driveway and ran over them with his truck until their bright-smelling green husks came off. After they were dried, I’d crack them on an anvil with a hammer, then pick out the meat with ten-penny nails.

And I especially shouldn’t have been lonesome because I had a brother, Wade. Once we were friends; we laughed so hard at supper one night Papa said he was going to send us to our bedrooms if we didn’t settle down. But when his new friend Gary showed up, Wade acted like he was embarrassed by me.

I didn’t want to play with them anyway. Gary was crude and creepy. And what kind of teenager has a fifth-grader best friend? But I still spied on them when I had nothing better to do. That’s how I saw what they were doing with Violet, Papa’s best Guernsey milker.

It was a hot day. I’d already helped Mama feed the chickens and collect the eggs. Normally, I would have been following Papa around on his chores, but he had business in Boise. If Mama knew I was bored she’d have found me chores to do, so I spent most of the afternoon in the cool basement reading a book I got from the bookmobile called Freddy the Detective, about a pig who solves crimes. I’d already read it once, but I read the one where Freddy goes to the North Pole three times, so it was relatively fresh by comparison. Papa hadn’t come home by three, and I wanted to look at the barn cat’s new kittens, so I emerged into the bright sun from the basement like Lazarus and headed for the loft.

I could hear Wade and Gary talking before I got to the barn. I knew Wade would be exasperated if he saw me, so I looked through a knothole in the silvery wood. Violet’s head was locked in a stanchion while Wade stood on a milking stool with his pants down having sexual relations with her.

Once, I asked Mama if people did the same thing as the animals. She said what people do is different. She said people do it with someone they want to spend their whole life with, to show them how much they love them. I was pretty sure Wade didn’t want to spend his whole life with Violet, and she didn’t seem to care one way or another. She just kept chewing on the alfalfa they’d tossed into her trough. I thought about running to the house to tell Mama but remembered Wade said people who tell are worse than skunks.

Anyway, if I was going to tell on Wade I wouldn’t know where to start. Boys just naturally do stupid stuff. Like when he made a dogwood bow and shot one of Mama’s Rhode Island Reds. The arrow didn’t kill the hen, but she ran off with it stuck in her side. When Mama pulled it out, some intestine came out too, so she had to cut her head off. Mama said it was a good laying hen and she had half a mind to tell Papa. I guess she wasn’t a skunk, or maybe she was worried about what Papa would do because he can have a temper. She did use it to get Wade to do extra chores.

By the end of June, Wade was gone on his bike most days doing stuff with Gary, while I followed Papa around. Sometimes he gave me stuff to do, like fetching a tool, water, or lunch, but mostly I watched him work from the shade. Papa had two mules to plow and haul the hay wagon. Mama named them Sofi and Stella, after his girlfriends before they met. Sofi was a sweetie, but Stella was mean as a snake, and on the Fourth of July she kicked Papa so hard we had to take him to Saint Luke’s in Boise. They hung his leg in the air with ropes and pulleys, and the doctor said it would be months before he could walk again. Mama was sick to death with worry over how the work would get done. And not just feeding the livestock and milking the cows. Papa had seeded the south pasture with alfalfa, and it was nearly high enough for reaping and ricking.

For the first few days after Papa was in the hospital, I fed the chickens for Mama, collected the eggs, and dealt with folks responding to our “Farm Fresh Eggs” sign at the end of the lane. I’d put the money in the egg money jar in the kitchen while she and Wade fed the pigs, sheep, and cows and did the milking. But she wasn’t a big lady, and he was a little kid, no matter what he thought. When they dropped a ten-gallon can of milk wrestling it onto Papa’s cart and it poured out onto the ground, she sat down in the dirt and cried.

It was Papa’s idea to hire someone to help out. We were near the rail line, and though the old passenger station was closed, the freight trains stopped there for water, so travelers “ridin’ the rails” would hop off to look for something to eat. Mama didn’t believe in starvation for any of God’s creatures, so she was an easy touch. Sometimes, if Papa needed a hand and the gentlemen were forthright, he’d take them on for harvesting or for projects where he needed a hand, like when he built the new barn to replace the one that was falling down around his ears, or when he fenced the pasture for the new alfalfa field. A few times when Papa needed a worker, he’d take his truck to the depot and wait for a train. He’d hire them on the spot if they didn’t look like a drunk or trouble.

Papa said this time we couldn’t just wait for some hungry man to wander by, then hope the guy didn’t have problems. Mama should drive down there to interview somebody for the job. They decided they could offer $30 a month, plus board. He’d have to be able to milk and tend to the animals, mend fence, and strong enough to reap and stack the hay. But she wasn’t to take on a drunkard, and she shouldn’t hire a murderer. Mama said that wasn’t funny.

Wade wanted to go with her, but Mama said he had to stay in case of egg customers since I was too young to be left alone. I was excited to go, even though she said it wouldn’t be like when we picked up Aunt Ruth at the train station in Boise and I got candy from the newsstand. The Kuna station had been locked up for years, so there wouldn’t be any treats, but I loved adventures and riding in Papa’s nice old truck that smelled of motor oil and dried-up leather.

We rolled past fields bright green from spring rain where huge white birds floated down to land on stilt legs among pure black cows, milkers grazed, truck gardens teemed with budding vegetables, and my favorite, a pasture where I could pick out my someday horse. That day there were two foals, and Mama stopped so we could go to the fence and say hello.

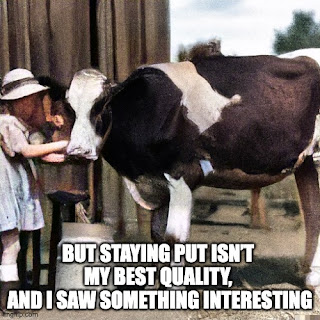

When we got to the station there were men who looked like they came on a train sitting on the steps smoking. Mama parked the truck, told me to stay put, then walked over to interview them. But staying put isn’t my best quality, and I saw something interesting, a man with a campfire by himself in a clearing in the weeds. I closed the truck door quietly behind myself and walked over to his fire.

He looked younger than Papa, more like Mama’s age, with black hair that touched his shoulders and strong features and hands. He was sitting on a bucket, but I could tell he was pretty tall, maybe taller than Papa. I thought he was handsome and said, “Watcha’ doin’?” Which was stupid because there was a coffee pot sitting in his fire.

“Makin’ coffee. Want some?”

“I don’t drink coffee.”

“You a Mormon?”

“No, I’m six years old.”

He had a friendly smile. “Oh, yeah, I see that now. You want some milk?”

He had a small bottle with the thick cream at the top, next to a frying pan and a bowl with two eggs. I said, “Doncha need it for your coffee?”

“Don’t need all of it.” He shook the bottle, then poured half in a cup and gave it to me. It was sweet like it just came from Violet. He laughed. “You got a mustache now.”

I wiped it off in a dignified manner and said, “What’s your name?”

“Jacob Ghost Bear. What’s yours?

“Stevie McKittrick.” I shrugged. “Actually Stephanie, but everybody calls me Stevie.”

“Sorry, I just got one bucket, but you can sit on this, Stevie.” He put a folded blanket down by the fire.

I looked back at the depot. Mama was busy talking to one of the men. Jacob seemed nice and I decided she’d want me to be friendly, so I sat down to talk with him for a spell. He put lard in the pan, broke the eggs into it, then tore off some bread and added it to the grease. When he set the pan on the fire, I asked him if he’d come on a train.

“That I did.”

“Why’d you get off here?”

“Those freight trains got no dinin’ car.” He laughed again. His laugh was deeper than Papa’s.

I said, “You looking for work?”

He seemed surprised.

“Wouldn’t turn it down.”

“Can you milk, and feed cows and pigs and sheep?”

“S’pose I can.”

“Can you mend fence and reap and stack hay?”

He turned the bread in the hot fat and shook the pan. “You lookin’ to hire me?”

“If you’re not a drunkard or a murderer.”

He withdrew the pan from the fire, dipped the bread in the golden yolk, and took a thoughtful bite. “No, little lady, not a drinkin’ man, and I believe in the Golden Rule.”

“It’s thirty dollars a month, plus board.”

He dipped his bread and ate, as if seriously considering my proposition, then nodded toward Mama, talking to a different man on the station steps. “And she say it’s OK for you to tell me that?”

That’s when Mama cried out, “Stevie!” and hurried over to us, looking worried.

I said, “Hi, Mama,” like I was glad to see her, but I could tell I was in for it so talked as fast as I could. “This is Jacob Ghost Bear. He can milk and feed cows and pigs and sheep and mend fence and reap and he’s not a drunkard or a murderer.”

Mama said, “I’m sorry, she repeats what she hears without thinking how it makes people feel.”

Jacob got to his feet and smiled down at her. “Your daughter knows her mind well for her age, ma’am. But I understand if you already pick somebody.”

“No, there was no one I trusted, and Stevie has good intuition. What she said was right. That’s what we’re looking for in a hand. It’s thirty dollars a month, plus board.”

“I told him that,” I said, exasperated, but Jacob just said, “That’ll be fine.”

Mama drove us to Saint Luke’s before we went home, so Papa could meet who we hired. Papa and Jacob were both quiet men. When they met, Papa in the special bed with his leg hanging in the air, Jacob politely holding his hat, Papa shook his hand and thanked him for helping us out. Jacob only said he hoped he’d be out of a job soon. But at home, Wade acted strange when Mama introduced Jacob to him, then took off on his bicycle, probably to tell Gary.

Mama had me show Jacob the bunkhouse. It was little, with only one bed, but it was a bunk bed, naturally. It was a nice place to sleep, especially hot summer nights. When you left the door and window open there was a breeze, and you could hear the animals and wild critters talking things over. I showed him the pump to fill the cistern for the shower and the outhouse Papa dug by the barn so he wouldn’t have to walk all the way back to the house to pee. The cows were clamoring by the barn door for their afternoon milking, and he got right to work. I helped him put feed in the stanchions and pumped water into their trough, telling him how that evil molly mule kicked Papa’s leg and how good the new Freddy the Pig book was.

Mama was pleased to see the cows back in the pasture when she shooed the chickens into the hen house. She told Jacob I’d bring his supper out about six, and he asked if he could make a fire for his coffee. Mama said he could help himself to the woodshed.

When I brought his supper out, he’d chopped some wood and was carrying it to the bunkhouse. I wanted to watch him make a fire, but my supper would be ready in a few minutes and I’d get my butt chewed if I wasn’t washed up and seated for grace.

Wade started off supper in the doghouse for being late coming home from Gary’s and dug himself deeper when he asked Mama why she’d hire a thieving Indian, that they are worse than niggers. As soon as it came out of his mouth, I knew it was from Gary. Mama told him she wouldn’t have that language in her house, and if she heard him say those words again she’d see Papa took the hide off him when he came home from the hospital.

When I collected Jacob’s supper dish, he had his coffee pot on the fire and was building himself a cigarette. Papa smoked sometimes but Mama was against it, so he only did it when someone offered him one. Then he could tell her it was only to be polite. Jacob said, “Best meal I’ve had in don’t know how long.”

“I’ll tell Mama. It’ll make her happy. If you got any washing, she said you should give it to me.”

“That’s kind of her. I’ll do that.”

I looked at the plate in my hand, wiped clean. “Well, good night, Jacob.”

“Good night. And, thank you, missy.”

In the morning I wolfed down my breakfast so I could watch Jacob milk the cows. Wade was doing his chores like he always did with Papa, feeding the girls, sterilizing the cans, and hosing the pee and dung from the milking room floor, but he and Jacob didn’t say a word to each other. Wade didn’t even warn him when our bull, Casanova, stuck his nose in the door. Papa once put a twelve-gauge load of rock salt in Cassie’s butt when the stupid bull tipped over a pail of milk, but Wade seemed to want something like that to happen. I threw a stanchion block at Cassie, and he ran off bellowing and kicking up his heels. But Jacob was so busy he didn’t notice.

Close to lunchtime I had a run of egg buyers while Mama was running errands, three cars in a row, the last one buying three dozen, almost all we had. Wade and Gary were in the kitchen, Wade making sandwiches. When I came in to get the eggs and change from Mama’s egg money jar, Wade said, “So how’s your boyfriend?”

Gary said, “Yeah, I hear you’re a Indian lover now.”

When Wade first brought Gary home, I was shy around him because he was nice to look at and confident, but now all I could think of was them having sexual relations with Violet. I wanted to tell him, “Well, that’s better than being a cow lover,” but I just got the eggs and change for the people waiting in their car.

Another car came an hour later, but there wasn’t even a half dozen left. Then Mama asked me to show Jacob how to walk ditch, set the gates, and tell him the irrigation schedule. She also said to show him the alfalfa that needed cutting, the tool and tack room, and the damn mules. I was proud she asked me and not Wade, but Wade and Gary were already gone, so she probably would have told Wade to do it if he’d been there.

I had on the yellow rubber boots Papa called my “Wellies” when I walked ditch with him. Sometimes we talked a little, but mostly we just listened and looked at stuff. We turned the water off at sunset so we’d be out there when the sky lit up pink and orange and purple. Papa would lean on his shovel, taking in the spectacle. Jacob just nodded when I showed him the gates and told him how long for each one. The water was high in the canal, moving too fast to swim. It would flood the pasture pretty fast.

We crossed over to the alfalfa field, which was on five acres that Papa fenced off from the pasture, then plowed behind Sal and Trina. Jacob opened the gate and we walked out into the green-smelling rows. He said, “Your mama’s right, it’s ready for the first cut. You got a scythe?”

I showed him the toolshed. The scythe was on a hook on the wall. Papa hadn’t used it since the fall and the blade was rusty. Jacob felt the edge, then poked around till he found the sharpening stone. He said he’d start soon as he got it good and sharp. When I was helping Mama feed and water the chickens, I saw him walk back out to the alfalfa field, the blade so clean it flashed in the afternoon sun.

That night when I brought Jacob his supper his hair was still wet from the shower and he had on the pants and shirt Mama washed for him. He told me to thank her. Papa called, and I told him it looked like Jacob made a good start with the alfalfa. I said I felt the edge after Jacob put the scythe back in the shed and it was so sharp he could shave with it.

When I went back out to collect his supper dish, Jacob was pouring himself a cup of coffee from the pot he had on the fire. He said, “Have a seat,” and gave me a turned-over bucket to sit on next to the fire.

“So, you drink coffee yet, or you still six?”

I said, “I’m still six,” as I admired his fire. “I’m sorry Wade’s acting so stupid.”

“He don’t seem too happy ’bout me bein’ here.”

“I don’t know why. When we play Cowboys and Indians, he always wants to be the Indian.”

Jacob took out his tobacco and cigarette papers. “Never understood why they call it ‘Cowboys and Indians.’ Should be ‘Soldiers and Indians.’ That’s who we was always fightin’.”

I said, “Do you want to hear a joke?”

He said, “Always want to hear a joke,” as he sprinkled tobacco on the thin paper.

I sat up straight on the bucket so I’d remember it in the right order. “Big Turtle, Middle Turtle, and Little Turtle went to a café to get some coffee, but just when the waitress brought it to them it started to rain. Big Turtle said to Middle Turtle, ‘It’s raining, go home and get the umbrella.’ Middle Turtle looked at Little Turtle and said, ‘It’s raining, go home and get the umbrella.’ But Little Turtle said, ‘If I go, how do I know you won’t drink my coffee?’ Middle Turtle said, ‘We’re not going to drink your coffee. Just go get the umbrella.’ Little Turtle said, ‘Promise you won’t drink it?’ and Big Turtle said, ‘We promise,’ like he was exasperated. So Little Turtle left to get the umbrella. Big Turtle and Middle Turtle drank their coffee slow. Turtles do everything slow. But Little Turtle still wasn’t back when they’d finished drinking their coffee. They waited all day. Finally, Big Turtle said, ‘Well, I don’t think he’s coming back.’ Middle Turtle said, ‘Yeah, I guess we should drink his coffee.’ Then, a tiny voice from behind the coat rack said, ‘If you do, I won’t go.’ ”

Jacob laughed like he really thought it was funny, not just to make a little kid feel better. Then he said, “So you want to hear a joke?” I said, “Yes!” and he told me the best joke ever. “A long time ago, the Dogs would gather in their great lodge to dance for the Winter Moon. After years of watchin’ them, Coyote decided it looked like fun and asked if he could join them, but the Dogs laughed at him and said no, he maybe look like a Dog, but he wasn’t a Dog.”

“Coyote’s feelin’s was hurt and he cried to the moon, but the Dogs still didn’t invite him. Anyway, Coyote watched them, hopin’ they’d change their minds, and on the next Winter Moon the Dogs held the biggest gatherin’ they ever had, with Dogs from everywhere, near and far, come to dance. Like always, Coyote asked if he could join them, and like always they laughed at him because he wasn’t a Dog. That night more Dogs came to dance than ever, and soon there wasn’t enough room for everybody. The Dogs didn’t want to stop, but they couldn’t spin around the way they like to dance without bumpin’ into each other. Then Coyote said, ‘If you take off your tails it will give you more room and you can race around much as you want.’ The Dogs decided this was a good idea. They took off their tails and hung them on the wall of the lodge. Then they danced crazier than ever half the night. But while they danced, they made a great wind and the fire grew too big, til it reached the roof. The Dogs was so busy dancin’ they didn’t see this, but Coyote did and shouted, ‘The roof is on fire, run!’ The dogs got out, but they forgot to save their tails, and Coyote, thinkin’ now he could get even for years of their bad manners, collected them in a bag. The Dogs was happy to see Coyote saved their tails, because they felt naked walkin’ round without them. But Coyote was still mad at them for not lettin’ him join in their Moon dance and said, ‘You wouldn’t let me dance with you. I should have left your tails in the fire.’ Then the Dogs was ashamed and said they was sorry. Coyote said, ‘I will return your tails, but when you reach in the bag, you must take the first one you find, and that will be your tail.’ The Dogs agreed to this because they was sure they would recognize their own tails. Coyote smiled to himself when the first Dog looked into the bag to claim his tail, because the fire made them sooty, so they all looked the same. The Dog said, ‘Let me clean them,’ but Coyote said, ‘No, you promised to keep the first tail you take from the bag.’ Now Coyote didn’t hide his smile as each Dog took a tail from the bag. A few was lucky and got their own tails back, but most didn’t. And that’s why Dogs sniff each other’s butts. They just lookin’ for their own tails.”

There was a white oak tree in the corner of the alfalfa field that had some nice grassy shade. I brought my library book to read again the next day while Jacob cut hay. He was about a quarter done, which was good since he’d spent half the day doing other chores. It was hot and I brought him a ladle and bucket of water to drink and pour on his head. I filled it for him a few times, then fetched the whetstone to restore the scythe’s edge. That’s when I saw Wade and Gary come out of the house. It looked like they were having an argument.

I didn’t think about it again until it was time for the afternoon milking, when Jacob put the scythe away and stanchioned the cows. I was on my way to the chicken coop, when I saw Mama come out of the house and go to the barn, looking upset. I followed her, and she told Jacob she knew he’d stolen her egg money.

I wanted him to deny it, to say he lived by the Golden Rule. But all he said was, “That so?”

I started crying, and Mama told me to go to the house. I watched from the front room till he’d packed his things and walked up the lane. After he was gone, I asked Mama how she knew Jacob took the egg money, but I already knew it was Wade, and I knew he wasn’t telling the truth. When I said that to him, he said Jacob was a thieving Injun and stomped out like he was mad. But I’d seen my brother lie before. He doesn’t look you in the eye.

I know he’s just a pig, but Freddy solves crimes by asking questions and looking at the evidence. After supper that night, I asked Wade what time he saw Jacob take the egg money. He said it was just before lunch. I didn’t say anything, but that was when I saw him arguing with Gary while I fetched the whetstone for Jacob. Then I asked him where he was when he saw Jacob go to the kitchen. He said he’d been right outside the kitchen window.

After I helped Mama with the dishes, I stood outside where Wade said he’d been. Just like I thought, I couldn’t see Mama or the egg money jar. Then I saw Wade watching me from the doorway. I said, “You didn’t see Jacob steal the egg money.”

He said, “I did so.”

“You’re lying. I can always tell.”

“It was that dirty thievin’ Injun.”

“You sound like Gary. He makes you do and say bad things.”

“He’s my friend.”

“He’s not your friend. You’re just a little kid he uses. And I know he stole the egg money. You’re gonna’ tell Momma the truth, or I’m gonna’ tell her what you did with Violet.”

His eyes got really wide. “How do you know that?’

“I saw you.”

“You wouldn’t tell. Then you’d be a skunk.”

“There are worse things than being a skunk. Like telling lies about a good person. And there’s something worse I could do besides telling Momma. Like when I start first grade and tell everyone you had sexual relations with a cow.”

Wade told Mama the truth. It was past our bedtime, but she said we were going to the depot in Papa’s truck, and she made Wade come, so he could damn well tell Jacob he was sorry.

Jacob’s fire was the only light at the depot, but there was moonlight, so we could see to walk over after Mama turned off the truck’s headlights. I guess the other men either got jobs or hopped trains because Jacob was the only one there. He didn’t look up as Mama herded us into the circle of firelight, a hand on each of our shoulders. But he did when my shamefaced brother said, “I’m sorry I told my mom you stole the egg money. It was my friend Gary did it.”

All Jacob said was, “That so?”