I quit Texas

after Lorelei troubled my waters. Ten, fifteen years ago. I drove to New Orleans, then Biloxi and Kansas City, wherever there was nine-ball action. If I found a motor court laid out like a horseshoe, I’d rent a room for a week. A month if the pool hall had Gold Crown tables, longer yet if I met a friendly waitress. I’d been hustling in Knoxville for a year before Jesse Vodinh kicked in my door at the Sunset Motel and accused me of throwing games. Jesse was a stake horse with a shaved head and an affinity for butterfly knives. I was alone again, on the plum-colored carpet, when my father told me that he’d seen Lorelei haunting our bayou. I hadn’t heard his voice in a decade, maybe more. My ears were humming. Jesse had rung my bell before flicking open his knife.

“Haunting?” I asked my father.

“Hunting,” he said. “For them skulls.”

He meant to warn me off but might as well have said, Come on home, son. You been gone long enough.

—

My father

was from the Louisiana side of Caddo Lake and afraid of witches. He believed that any cat, if allowed in the house, would suck your breath clean out. A loose hog was someone under a spell. Or a sign an heir had died and the family didn’t know.

He moved to Uncertain, Texas, with my mother, though she soon left him for a tent preacher. I kept thinking we’d move, and he kept thinking she’d come back. We were both wrong. My father took work as a guide on our bayou, showing oil-men where to fish for bluegill and running swamp tours for their families. If he saw a white owl, he’d cut the tour short. If the ghost lights were firing, he’d tell the tale of Feu Follet. My father’s voice was quicksand.

—

Uncertain, Texas

is where you wind up if you’re lost. Or aim to be. Cabins and bars and churches. Old Guthrie and Wanda own their bait stand and rent out canoes. Guthrie says, The town’s called Uncertain because Caddo Lake spans the Louisiana and Texas border, making the town limits impossible to map. Wanda says, The original township application had a box asking for a name and whoever filed the paperwork didn’t know what to put, so they just wrote Uncertain. Guthrie says, Really ain’t nobody knows why.

When I got back, I asked Guthrie if they’d seen Lorelei. Wanda said, Someone stole another rental canoe two nights before. Guthrie said, I thought it was three nights. Wanda said, Who cares—gone is gone.

—

Lorelei had a barbed wire heart

tattooed on her shin. A crescent moon on her knuckle. She spent days collecting feathers and bones and skulls from the swamp. She arranged them in sacred shapes, fashioned them into jewelry. When we started up, one of us would say, “Swamp’s easy to get lost in,” and we’d meet in the backwater. With her, in those sepulchral bogs, the world fell away, and she taught me how much I didn’t know. We always seemed on the edge of something dangerous and irrevocable—love, say, or being caught. Once, we happened upon a copperhead skeleton so pristine it might have been carved from alabaster. Another time, in the black mud of Potter’s Point, we found a sharply bowled bone that she identified as a pelvis. She took it home and kept keys in it, loose change.

—

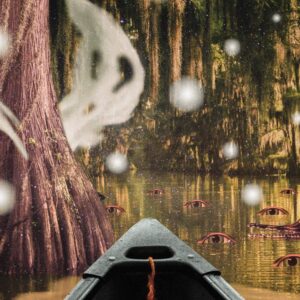

A ghost light

is also called a corpse candle—a luminescent sphere just above the swamp. You can go a lifetime without a glimpse, then one night the water will be ablaze. It hovers, darts, disappears. It can be as mean as a cottonmouth, as mischievous as a child. The closer you get, the farther the light recedes. A lantern flickering across a dark field, a porch lamp burning for someone who isn’t coming home.

—

From above

Caddo Lake looks like a horse galloping westward. The bayou channels are thick with bald cypress, gnarled and twisted and centuries old, and Spanish moss shrouds their limbs like shoals of silver fog. Salvinia is choking the swamp. It suffocates everything below the surface and blots out the sun. Guthrie thinks somebody bought it for their aquarium, got sick of it smothering their fish, and hucked it into the lake. Wanda says, That weed wants to turn Caddo into a prairie. Guthrie says, That’ll be the end of us.

Feral donkeys graze in a copse of cottonwood. The branches of a crape myrtle bloom with cobalt-blue bottles. A poacher had moved into Lorelei’s old cabin, and a dead gator hung from a rope in a hickory out front.

—

Playing the ghost

is a lonesome game of pocket billiards. You rack the balls and break, then place the cue ball anywhere on the table for your first shot. Miss after that, even once, and you lose. The ghost never misses.

A few days before Jesse found me at the Sunset, I was racking the balls and explaining the game to a waitress. Her hair was bleached, and she was wearing fringed boots. I hoped she might prove friendly. I said it’s like solitaire, and she said solitaire used to be called patience. Witches read the game like tarot cards and told fortunes.

“I didn’t think people from Tennessee believed in witches,” I said.

“I wouldn’t know,” the waitress said. “I’m not from here.”

“I’m out to make a fortune, not tell one,” I said.

She slipped a pen from behind her ear, scratched her address onto a napkin, sank it in the corner pocket.

—

Feu Follet

is another name for ghost light. The Cajun fairy. My father believed she toyed with fishermen for sport. Guthrie says, It’s the burning soul of an unbaptized child. Wanda says, That’s pure horseshit. She was sent back by God, meant to be doing penance but turned spiteful. Feu Follet makes folks believe they can catch her, gets them so disoriented in the bog they never come out. Guthrie says, What makes you so sure she’s a woman? Wanda says, She’s a fairy, ain’t she? Besides, it’s only men who go missing—men and my canoes. Guthrie says, Maybe men are just stupider. Wanda says, I can shake hands with that.

When we spotted the pelvis in the black mud of Potter’s Point, Lorelei said, “Feu Follet strikes again.”

—

The waitress

lived in a shotgun shack with her boyfriend. He shook my hand without squeezing and said, “Call me Darkness.”

—

The bottle tree

was on the old Guillot homestead. Guillot believed any evil approaching the house after dark would be enchanted by the cobalt glass. Spirits slid inside and were trapped, then seared by the sunrise. When breezes came through the marsh, the bottles whistled—the last song of the wicked.

The sky was purpling with dusk when I found Lorelei admiring the bottles. Her back stayed to me. She touched one bottle, then another, like a child hanging ornaments. Without turning, she said, “I thought you were in Knoxville.”

“My father said you’d come home,” I said.

She twisted to meet my eyes, bemused, as if she’d caught me lying. Turning back, she said, “Your daddy never liked me.”

“He liked you plenty,” I said. “He didn’t like you being married.”

“I’m not married now,” she said.

“Wanda thinks you stole a canoe.”

“I just cut it loose,” she said. “That’s not stealing.”

A barred owl called from the shadows. Lorelei pivoted to face me. Her gaze seemed a reckoning, like my virtues and trespasses were being weighed against one another.

“Swamp’s easy to get lost in,” she said.

“Yes,” I said.

—

Darkness

wore a starched white shirt, black suspenders. The devoutly dressed hustler. The waitress had marked Jesse Vodinh long ago—he flashed his jellyroll every time he paid for a drink—so they’d been looking for someone to help cut him up. The plan went like this: Darkness would notice me playing the ghost and make a show of challenging me to a race to twenty. I’d accept, but when he wagered five large, I’d say that was too rich for my blood. We’d make sure Jesse overheard, knowing he’d offer to stake me for a percentage. Darkness and I would keep the race tight, but he’d pull away at the end and leave with Jesse’s cash. On my way out of Knoxville, I’d stop by the shotgun shack for my half. It should’ve worked.

—

In the end

we stole one of Wanda’s canoes and rowed into the swamp. We knocked into cypress knees, threaded through their corded trunks. A flock of white egrets stood so close together they might have been a reflected moon. The night was oil black and smeared with stars.

“What happened in Knoxville?” Lorelei asked from the bow.

“I wore out my welcome,” I said.

“I was planning to visit you,” she said. She was lying, and I was flattered. She dipped her hand into the lake and dragged the surface, water furrowing between her fingertips. “You saved me a trip.”

“You’ve always been patient,” I said.

“Tyler,” she said. “I’m sure sorry about your daddy.”

I leaned into the oars, then again, harder. We displaced swaths of lily pads—lotus flowers swaying as if brushed by an unseen hand.

“How’d you know?” I asked.

“You said he’d told you I was back,” she said.

“He did,” I said.

“That’s how,” she said.

—

After

Jesse accused me of throwing the race, he went into my bathroom and washed his knife. The music of running water, the metallic scent of spilled blood. I lay on the plum-colored carpet, hearing my dead father’s voice. Jesse killed the lights before he left, closed the door behind him. Come on home, son.

—

The swamp

narrowed. The cypresses closed in. Ragged curtains of moss formed a long tunnel. Water folded over the oars like bolts of cloth.

I said, “So you’re—”

“Here,” she cut me off. “I’m here. With you.”

“And my father?”

“He’s around somewhere,” she said.

“So then I’m—”

“Right where you’re meant to be,” she said. “Lost in the swamp.”

“I don’t understand,” I said.

“I know,” she said, like an apology.

Behind Lorelei, the lake laid claim to the horizon. My bearings were gone. We could have drifted out of Texas and into Louisiana or some dark province rinsed of time and border, of names and other lies.

—

Beyond

the cypress brakes, the swamp opened, and we crossed into glassy water. We floated through stars reflected on the surface. They undulated, then returned to their inauspicious stations.

In the distance, a flickering ember. A candle lit for the dead. On the wind, the scent of a struck match.

“Feu Follet,” I said.

“Strikes again,” Lorelei said.

—

I reached for her hand

and she was gone. Or she had never been there at all. Or I hadn’t. My vision tunneled, and the distant ember flared, as if being coaxed to flame. I felt certain it would snuff out, and with it, my life. Okay, I thought. Okay, I’m ready. Then, at once and everywhere, the lake was nothing but spectral light. The balls rolled and spread, caroming off each other. I was terrified. I was fearless. When I dove in, I made no splash. The water cradled my body like a sleeping child, lowered me to the endlessly forgiving silt.

Above, the lake burned, and in the twisting colors, I read a fortune: the dead gator slips its noose and crawls under the porch to await the poacher’s ankles, his knees, his throat, then returns to its ancestral waters, sated and magnificent. The lake rises. It spits out our bitter bones, rids itself of every parasite and poison. A white owl flies from the mossy veil. The bottles sing and fall silent. Wanda locates her canoes. She says, Some kid likely played a prank. Guthrie says, I might not have tied them good, I don’t know, it’s a mystery. Then Wanda hears noise in the brush and says, What’s that? Guthrie says, A mystery? It’s a question that ain’t yet been solved. Wanda says, No, dummy, what’s that noise? Guthrie cocks his head, listens. That? he says. That’s just a hog rooting around for supper. Wanda says, Ain’t that supposed to mean something, a loose hog? Guthrie says, It means someone needs to patch a fence. Wanda says, No, there’s more to it, an old lesson or truth, something we’re surely missing.

Corpus Christi native Bret Anthony Johnston is the author of the novel Remember Me Like This and the director of the Michener Center For Writers at the University of Texas at Austin.

This story is published in collaboration with Texas Monthly magazine. It will appear in the photographer Keith Carter’s book Ghostlight (UT Press, November 2022).