Few things are more unnerving three years into a pandemic than public health officials talking about unusual outbreaks of yet another virus, but here we are.

Since early this month, officials have been watching an uptick in cases of the monkeypox virus around the globe. While the virus is endemic in countries in central and west Africa, it’s now been detected in 21 countries — predominantly in Europe — where it’s not typically found. As of May 25th, there are 227 confirmed cases and 90 suspected cases globally, according to Global.health, which pulls from public health databases around the globe. In the United States, there has only been one confirmed case in Massachusetts, though there are a handful of presumed cases.

While there was initial concern that so many cases in non-endemic countries meant that the virus could have evolved in an unusual way that makes it more transmissible, initial genetic sequencing suggests that’s not the case. More research needs to be done to definitively determine if the virus has mutated significantly. The sequencing suggests the virus is the type associated with West Africa, which has a fatality rate of about 1 percent, according to the WHO. Here’s what we know and don’t know about monkeypox and the current outbreaks.

What is monkeypox?

As the name suggests, monkeypox is in the same family of viruses as smallpox, though typically it is much less transmissible and far less severe than smallpox.

William Schaffner, an infectious disease expert at Vanderbilt University Medical School, tells Inverse the virus is typically found in small mammals in areas with tropical climates.

“Occasionally, it does get into primates, that’s why the name monkeypox,” he says. “And of course, it can also get into people. It can be spread from person to person but not easily, you need very close and usually fairly sustained interpersonal contact, touching, kissing, and such.”

The World Health Organization notes that the longest known transmission chain of monkeypox is “nine generations,” meaning the last person to be infected in this chain was nine links away from the original sick person. That’s up from six generations previously, suggesting some increased transmissibility, though if that’s truly the case and if so, how much more transmissible has yet to be determined. It can be transmitted through contact with bodily fluids, lesions on the skin or on internal mucosal surfaces, such as in the mouth or throat, respiratory droplets, and contaminated objects.”

The first case in the 2022 outbreaks was fairly standard, the person had traveled to Nigeria, where the virus is commonly found. The others, however, haven’t followed the same pattern: As of now, patients recently confirmed to have monkeypox in the U.S. and Europe don’t have known contacts with people with monkeypox and didn’t recently travel to an area where it’s common. So how they got the virus is still unclear.

The virus has an unusually long incubation period — between five and 21 days — which may have contributed to people not knowing they were infected and thus transmitting the virus

In an interview with STAT News, Andrea McCollum, who heads up poxvirus epidemiology in the CDC’s division of high consequence pathogens and pathology, said we may not have a full understanding of how this virus is transmitted generally.

“We don’t have really good contemporary estimates of R-naught. [R-naught is the figure that estimates how many people an infected person, on average, will infect.] We don’t really have any estimates of R-naught for the West African clade. Most of our estimates come from Congo Basin. And most of those estimates are less than 1. But I will remind you that you can have an R-naught of less than one and the agent can still be transmitted person to person.”

What are the symptoms of monkeypox?

By all accounts, contracting monkeypox sounds unpleasant. Symptoms typically appear anywhere from 5 to 21 days after exposure.

The symptoms are initially very similar to a bad case of the flu, Schaffner says.

“When you get sick, fever is prominent, it can go up to 103. You get symptoms that are similar to other viral infections, muscle aches, pains, headache, and swollen lymph glands.”

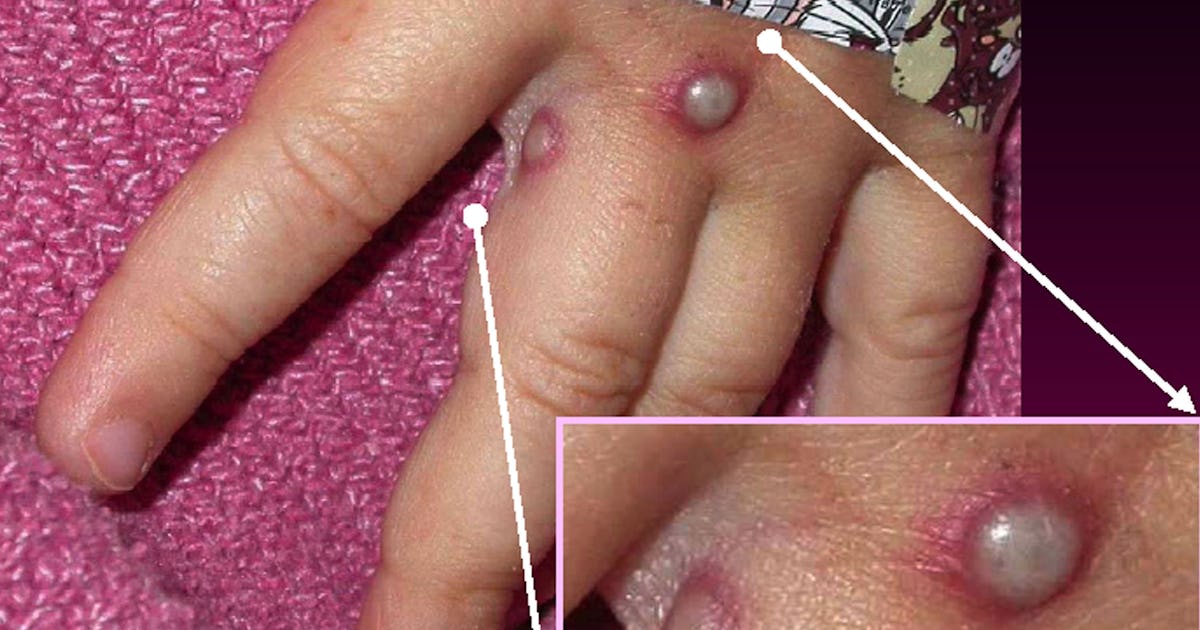

After a day or two of symptoms appearing, an “unusual” rash will appear, typically on the extremities like the head, arms, legs, and notably the palm of the hands.

“The rash initially is a flat red rash, but then it quickly blisters up,” Schaffner says. “But it’s not a thin blister. It’s a rather thick, rubbery blister, that accumulates pus and gets yellow.”

Unlike bites from a similar-sounding virus, chickenpox, the lesions from monkeypox are more painful than itchy.

Today, the average fatality rate falls between 3 and 6 percent, according to the WHO.

How do you prevent and treat monkeypox?

The smallpox vaccine(s) offers some protection against monkeypox, Schaffner says, though the majority of Americans who have been vaccinated for smallpox were vaccinated so long ago that immunity has waned significantly. Still, he adds, “people who have received a smallpox vaccine may have less severe symptoms if they do contract monkeypox than someone who has not.”

There are no approved antivirals for monkeypox, though the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security notes, “The antivirals cidofovir and brincidofovir could be used to treat monkeypox, though there is insufficient data on their effectiveness for monkeypox treatment in humans. However, animal studies have demonstrated effectiveness against monkeypox in certain mammalian species.”

Where have recent cases of monkeypox been found?

What’s unusual about these cases is how many of them have been found outside Central and West Africa. Cases have now been reported in the United States, Canada, the UK, Portugal, Sweden, and Italy.

That’s certainly concerning, Schaffner says, but perhaps not as concerning as some on social media have posited where conspiracy theories and general panic abound.

In some cases, the instinct to panic is likely a trauma response to living through three years of a global pandemic.

“We’re all infection and pandemic sensitive, I recognize that,” Schaffner says. “But I think the important thing is public health officials picked this up right away. They’re doing investigations and clinicians are treating the patients. Will there be more cases? Of course. The harder you look as you’re getting into an outbreak, the more you’re going to find.”

This article was originally published on