Tokyo

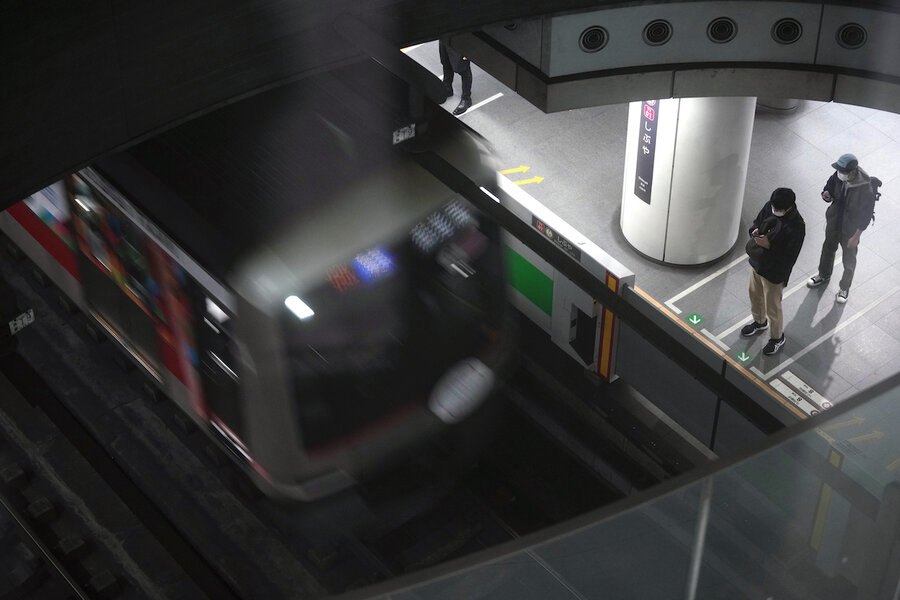

Tokyo’s Shibuya neighborhood is famed for its Scramble Crossing, where crowds of people crisscross the intersection in a scene symbolizing urban Japan’s congestion and anonymity. It may have added another boasting right.

Tokyu Railways’ trains running through Shibuya and other stations were switched to power generated only by solar and other renewable sources starting April 1.

That means the carbon dioxide emissions of Tokyu’s sprawling network of seven train lines and one tram service now stand at zero, with green energy being used at all its stations, including for vending machines for drinks, security camera screens, and lighting.

Tokyu, which employs 3,855 people and connects Tokyo with nearby Yokohama, is the first railroad operator in Japan to have achieved that goal. It says the carbon dioxide reduction is equivalent to the annual average emissions of 56,000 Japanese households.

Nicholas Little, director of railway education at Michigan State University’s Center for Railway Research and Education, commends Tokyu for promoting renewable energy but stressed the importance of boosting the bottom-line amount of that renewable energy.

“I would stress the bigger impacts come from increasing electricity generation from renewable sources,” he said. “The long-term battle is to increase production of renewable electricity and provide the transmission infrastructure to get it to the places of consumption.”

The technology used by Tokyu’s trains is among the most ecologically friendly options for railways. The other two options are batteries and hydrogen power.

And so is it just a publicity stunt, or is Tokyu moving in the right direction?

Ryo Takagi, a professor at Kogakuin University and specialist in electric railway systems, believes the answer isn’t simple because how train technology evolves is complex and depends on many uncertain societal factors.

In a nutshell, Tokyu’s efforts are definitely not hurting and are probably better than doing nothing. They show the company is taking up the challenge of promoting clean energy, he said.

“But I am not going out of my way to praise it as great,” Professor Takagi said.

Bigger gains would come from switching from diesel trains in rural areas to hydrogen-powered lines and from switching gas-guzzling cars to electric, he said.

Tokyu paid an undisclosed amount to Tokyo Electric Power Co., the utility behind the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster, for certification vouching for its use of renewables, even as Japan continues to use coal and other fossil fuels.

“We don’t see this as reaching our goal but just a start,” said Assistant Manager Yoshimasa Kitano at Tokyu’s headquarters, a few minutes’ walk from the Scramble Crossing.

Such steps are crucial for Japan, the world’s sixth-biggest carbon emitter, to attain its goal of becoming carbon-neutral by 2050.

Only about 20% of Japan’s electricity comes from renewable sources, according to the Institute for Sustainable Energy Policies, a Tokyo-based independent nonprofit research organization.

That lags way behind New Zealand, for instance, where 84% of power used comes from renewable energy sources. New Zealand hopes to make that 100% by 2035.

The renewable sources driving Tokyu trains include hydropower, geothermal power, wind power, and solar power, according to Tokyo Electric Power Co., the utility that provides the electricity and tracks its energy sourcing.

Tokyu has more than 100 kilometers (64 miles) of railway tracks serving 2.2 million people a day, including commuting “salarymen” and “salarywomen” and schoolchildren in uniforms.

Since the nuclear disaster in Fukushima, when a tsunami set off by a massive earthquake sent three reactors into meltdowns, Japan has shut down most of its nuclear plants and ramped up use of coal-fired power plants.

The country aims to have 36%-38% of its energy come from renewable sources by 2030, while slashing overall energy use.

Tokyu Railways has sought to publicize its effort with posters and YouTube clips.

Still, Ryuichi Yagi, who heads his own company that used to make neckties but has switched to wallets appeared surprised to learn he was riding on a “green train.”

“I had no idea,” he said.

Mr. Yagi switched his business because of Japan’s “cool biz” movement. It encourages male office workers to doff their suits for open-necked short-sleeve shirts to conserve energy by keeping air conditioning to a minimum in hot summer months.

In a sense, he said, “I lead a very green life.”

This story was reported by The Associated Press.