Daphne holidays on a Greek island to try and escape her worries, but she cannot escape her own body; by Birgit Lennertz Sarrimanolis.

|

| Image generated with OpenAI |

For the past few days, rain clouds scudded and hung low and dark on the mountain, sheathing its peak in gray fog. The three monasteries – Agios Sotiris, Agios Barbara, and Agios Prodromos – were just barely visible from the small port town at the base of the mountain, tiny specks on a looming mountain façade. When Daphne first arrived she questioned her timing for a holiday on a Greek island. There was little promise of the warm spring temperatures she had anticipated. She had jumped at the chance, though, when her friend Pavlo, who owned a small hotel in the port town, invited her to stay for a week. Winter had clung on too long. Leaving Athens, a sea of concrete and blaring horns and humanity, seemed like the right thing to do.

“Protomaiou is a magical time on the island,” Pavlo told her. “On the first of May, everyone goes out into the fields to pick flowers.”

But there was only a scattering of paparounes, red poppies, that should by now have swathed extravagantly across meadows. Everything was a little late this season. The mouries, mulberry trees, that stood along the harbor road were cut back, revealing stark branches. Pavlo assured her that their forgiving leaves would fill in broad and green just as soon as the sun warmed them a little. The almonds that hung on trees were still soft and fleshy white in their casings. The mousmoulia, loquat trees, bearing early yellow fruit that tasted of a blend of apricots and plums, were just starting to ripen.

“Einai noris akoma,” the fishmonger told Daphne as she walked along the harbor road early in the morning, soon after the fishing kaikia returned with their catch, to look for her favorite seafood. Too early yet for calamari. “Come back in two weeks,” he advised.

The locals were still cleaning up, burning brush they had cleared from beneath the olive trees in their orchards, making repairs to the shutters of their houses that had withstood the wind all winter, filling cracks in the flagstones along the quay. Spring, this year, toyed with patience, thumbing its nose against predictability.

Daphne wandered through the town’s narrow, cobbled alleys, peering through windows of shops that were crammed with straw hats and imitation black-figure Greek vases and colorful nautical souvenirs. On the beach recliners were still piled up at the edge of the sand, waiting to be arranged, and sun umbrellas were clasped down. Tavernas hesitantly opened for the first weekend of the season. Waiters set up tables, decking them with blue-and-white-checkered tablecloths, but kept plastic awnings pulled down against the wind and turned space heaters on in the evenings.

“I wondered why you wanted to come off-season,” Pavlo said when Daphne made a remark about the cooler weather. “You are always welcome, of course.” His brow wrinkled with concern. “Is there something bothering you?”

They sat in the little front room of his hotel, where he typically served breakfast to his boarders. “Full English breakfast,” he announced in the mornings with a broad smile, carrying a tray laden with omelets and sausages and orange juice. Now it was just the two of them, sipping strong Greek coffee out of miniature cups. Everything is off-season this year, Daphne thought, but she gave Pavlo a small smile to reassure him that all was in order.

They had been friends for a long time, since their university days together in Athens, where he studied business management and tourism before he returned to the island to open a small hotel. Daphne stayed on in the city, taking classes in archaeology and ancient philosophy. She liked the cosmopolitan life of Athens, the museums, the pulse of city life. But now she blamed her escape on the same city, saying the density of urban living made her crave the open island, its views of the Aegean Sea, the walks high on the cliff.

Pavlo eyed her but said no more.

Daphne had imagined, after the operation, that there would be two small scars on her chest, half-moons, like smiles. But the double mastectomy left caved-in, bruised flesh. The stitch marks that the surgeon had placed turned out well, he told her. To Daphne, however, they looked ragged. It took all her courage to remove the bandages for the first time because she was forced to look at herself in the mirror to empty the drainage tubes still stitched into her side. The body she had known all her life looked unfamiliar, almost grotesque.

“We could try a different regimen of chemotherapy and radiation,” her doctor advised at her appointment, consulting the mammogram and biopsy results. “Instead of immediately undergoing radical surgery?”

He was a small man, with a beak of a nose, thinning hair, and a sympathetic look that she imagined came in tandem with his profession. They had been through it once already, four years ago. This was her second diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ, once again in the left breast. The doctor tried to persuade her onto a more conservative path, emphasizing that she was young and still unmarried. She had not yet borne children. A mastectomy would dramatically change her life: her self-image, a future husband, breastfeeding babies.

Despite what he said, Daphne was adamant. She was traumatized the first time: undergoing a lumpectomy, thirty-three sessions of exhausting radiation, then four years of suppressive Tamoxifen pills. Only to have the cancer come back. If she opted for a mastectomy, she could eliminate the worry about the cancer returning in a more advanced stage, metastatic, more difficult to get into remission again.

She was not prepared for the profound sadness that followed the surgery and the subsequent building of anger against the world. Getting cancer had now happened to her not once, but twice. She looked at herself in the mirror and felt her heartbeat, steady and rhythmic, beating beneath the scars. It seemed to pulse more perceptibly now that the breasts that had once cushioned it were gone. She would have to protect it, fortify it with a different bulwark, to make sure it would not break.

She lived within the palisade she built around herself, a fence that grew stronger and more impenetrable with each passing day. She distanced herself from her friends, even when they brought her loose tops and camouflaging scarves to drape over her concave chest or a healing lavender plant with pale-green leaves folded up against the stalk, purple blooms clustered at the tip. She balked at her parents when they offered their help while she recuperated, her mother’s ministrations as she brought avgolemono soup and changed her bedsheets, her father’s consultations with her doctor as to her follow-up care. She imagined herself with a boyfriend, how he might reach for her in the night. His hand, touching her breast gently as he edged closer, dropped down and embraced her waist instead.

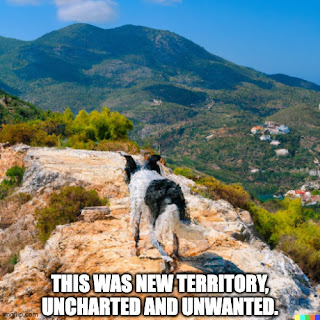

This was new territory, uncharted and unwanted.

When the weather turned and the skies opened to tentative sunshine, Daphne pulled on her hiking shoes, stuffed an anorak into her backpack just in case, and let herself quietly out of the hotel, careful not to wake Pavlo. At the bakery on the port road, she bought bottled water and a sandwich and then set off, eyes set on the distant Palouki mountain. She climbed up through the steep alleys where the townsfolk had yet to stir and soon found herself beyond the town. It was not difficult to find the trailhead that Pavlo had described, just beyond a fork of a smaller road leading up into the mountains.

The monopati, a rough, rooted mountain trail, ascended steeply, and the elevation gain was rapid. The trail was used long ago by mules delivering supplies to the lonely monasteries, fortress-like structures with thick walls and small windows. According to Pavlo, a single monk still lived in one of them in solitude, shuttered from the world. Nowadays only shepherds moved their flocks along the path from one mountain pasture to another. And the occasional hiker who, like Daphne, marked their own pilgrimage. She sought out the monasteries not for any religious purpose, since her upbringing had been largely secular by Greek standards, but because she, too, had fortified herself with walls and encased her heart in stone.

She tripped on rocks in her ascent, stopping every so often to wipe the perspiration from her forehead. From an outcropping Daphne gazed down at the sea. The port town looked tiny from her height. And still she had not reached even the first monastery. At a twist in the trail, Daphne caught sight of a cluster of tall, dark-green cypress trees that often marked the presence of a cemetery. She knew that she was nearing the first monastery.

Agios Sotiris was a whitewashed structure with a red tiled roof that surrounded an inner courtyard. Approaching it, Daphne could just make out the top of the church belfry in its midst, protected by the thick, fortress-like walls. Small, slit windows peered down from above, and a wooden balcony with a pulley system, presumably to haul supplies into the structure without having to open the heavy courtyard doors, looked down from above. Built precariously high above the sea, purposely difficult to reach, it still stood sentry to the past dangers of marauding invaders.

All was quiet. There was no sign of the solitary monk who still lived sequestered within the monastery walls. Daphne walked along the outer wall to a small, terraced vegetable garden, where she recognized the leaves of a few tomato plants, the tendrils of cucumbers, and the spreading leaves of green beans. It would be some time yet before the monk could harvest any vegetables. At a nearby vrisi, an outdoor faucet, Daphne gratefully let cold water splash onto her arms. Just as she filled water in her cupped hands to rinse her face and neck, she turned to a scrabbling sound behind her. It was a small dog, black and white and rather straggly, not a breed identifiable to Daphne. He sat with ears cocked, watching her ablutions. Daphne turned back to the cleansing water.

She sat on the stone terrace wall to rest for a while before continuing the trek that would lead her to the next monastery. When she readied herself to go, the dog followed.

“Go home!” Daphne said firmly.

The dog trotted up to her instead.

“Stay!” she tried again with a different command.

The dog tilted his head sideways, then wagged his tail with no intention of returning to the monastery. He probably belonged to the monk. It was not uncommon for monasteries to have watchdogs, trustworthy sentinels in the courtyard. Perhaps he alerted the monk when a stranger approached the monastery to light a candle or to leave a few coins in the monastery’s gift shop that sold honey, olive oil, sweet glika, and religious icons.

The dog’s demeanor was not fierce. On the contrary, he seemed amiable. Daphne imagined that he might be a loyal companion to the monk, sitting beside him for a long time while the monk meditated and prayed.

Prayed to a God that had neglected her. One who let disease torment her when he should have protected her, Daphne thought bitterly. Ache and damage flooded her again.

She set off on the trail, this time with angry steps, quickening her pace, dog forgotten. It was not until much later, when she paused to catch her breath and looked back over her shoulder, that she realized the dog was still following her. Daphne shrugged and continued walking. He would have to find his own way back home. The farther she went, the more determined the dog seemed to be to accompany her. A few times he took an offshoot trail, following a scent perhaps, but always returned to follow closely at her heels. Daphne ignored him and let the landscape soothe her. She could smell the scent of the heady pines growing thick and the wild mountain thyme crushed beneath her feet. The tinkling of goat bells and plaintive bleating came to her from far below, carried on the wind. Her anger slowly dissipated.

The path kept climbing and reached the other two monasteries, Agios Barbara and Agios Prodromos. They faced each other across an alpine valley, clinging to the mountainside, as though they were looking out for each other. Surrounded by fort-like walls, they reminded her of medieval fortresses, exquisitely Byzantine. Both lay slumbering in the warmth of the day, iron gates clasped shut. Only goat pellets on the footpath crossing the steep mountain meadow between the monasteries attested to any visitors at all. Pavlo told her no one lived in the monasteries on the top of Mount Palouki anymore. They were opened once a year for a church service on the Saint’s Day they were named after, when a modest congregation made it up the mountain to attend a liturgy.

Daphne took in the sight of the cloistered structures, where time seemed to have stopped. When she sat down beneath a pine to drink from her water bottle, her canine companion lay down next to her, panting, tongue hanging. Taking pity, she poured some water into the palm of her hand, which the dog gratefully lapped up.

“What makes you stay up here?” she asked him and got a thump of his tail as an answer. “Isn’t it too lonely of a life?”

They sat together for a long time, away from the rest of the world, like tiny mountain flowers sheltering behind rocks. The dog by her side looked up at her from time to time but did not question her choice to remain seated. Hours slipped by. When, at last, Daphne got to her feet to start the long descent from the mountaintop, she was wrapped so deeply in her thoughts, she did not heed any attention to the dog. Even when they reached Agios Sotiris, the monastery of their first encounter, Daphne did not pause until she heard the dog whine behind her. He took a few steps toward the monastery gate, then looked back at Daphne, as though torn between loyalties.

“It’s alright,” Daphne told him. “We both need to go home.”

That evening, in the front room of Pavlo’s hotel, Daphne spoke to her old friend. For many months her malaise was so deep, she was unable to give up its iron grip, clamping her heart shut even when she yearned for the gentle touch of a friend’s hand. But the scent of the day on the mountain was still fresh, and Daphne found her barricade crumbling a little. Pent-up feelings tumbled out in a rush, words tripping over each other, her voice thick with emotion. Pavlo looked at her sadly, long after she recounted her medical tale.

“And to think that all my life I had complained about being small-chested,” Daphne said, shaking her head at the irony. “Until my diagnosis. Then my breasts were no longer ‘unremarkable.'”

It was still difficult to find the good in her surgery, but she was willing to acquiesce to some benevolence in the ordeal. She could accept that her decision had perhaps spared her even more suffering in the future, even if spring was not asserting its presence fully yet.

“It was a long, hard winter for you,” Pavlo sympathized.

Daphne’s face held the reflection of a smile. The day had allowed her to find her way to three monasteries built into a steep mountainside, peaceful and serene, connected only by a rugged, twisting trail. She had breathed in the scent of the mountain and taken in views that were far and constant. And her heart was softened by the fidelity of a small dog that broke her solitude. She could lean into the promise of a gentle force slowly persuading winter to surrender.