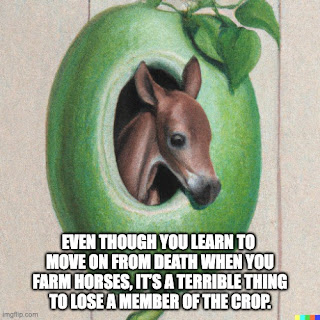

Farmers Jemery and Jezzie face a problem when two horses are growing too close together on the vine; by David Henson.

|

| Image generated with OpenAI |

I was concerned as soon as the horse pods began to sprout on the vine. The last two, Eleven and Twelve, seemed too close. Now that the pods are about the size of my leg, it’s clear there’s a problem.

“Should we cut a tendril now and transplant one, Jemery?” Jezzie says as she ties a red bandana to keep her hair out of her eyes.

My wife’s mane was pure black when we met. Now her hair boasts streaks of white. I tell her they’re like lightning – striking. When I complain about my receding hairline, she says it makes me look wise. I point out that when the snow caps to our west retreat every summer, the rocky peaks don’t look wise. They look bald. It’s all in fun. Keeping things cheery helps us get through difficult times. There are plenty of them when you grow mustangs.

Transplantation is tricky, and we rarely attempt it. “I’m concerned that would be too big a shock,” I say to my wife. “I think we should wait till the foal kicks out of the pod and is stronger.”

Jezzie sighs. “Seems like there’s one complication or another with every crop.”

Horse farming’s tough. Even though my grandfather helped populate the valleys with thundering herds, my father elected to take on cultivating javelinas. Not that working an orchard of trees heavy with grunts and squeals isn’t also challenging. My brother took over the javelinas. I answered a calling from equines. If I hadn’t, I might not have married Jezzie.

I first met my future wife at her parents’ garage, where my folks got their pickup truck serviced. I was smitten with Jezzie the first time I saw her. When I approached her at a school dance, she said her parents didn’t want her involved with a “smelly javelina farmer.” They softened when I chose farming mustangs, which they considered to be noble beasts. So are javelinas, but I didn’t argue. I was happy just to have their blessing to marry Jezzie.

My wife and I have a small spread – a one-room house, stables and up-ground cellar, all built by my great grandfolks. We have electricity now, farmed from wind off to our east. We’re too far from town for the public water supply, but there’s a well and a stream that swells with mountain snowmelt. Like most horse farms, we have a small stand of hay trees. When people say we live two steps from the middle of nowhere, we thank them.

Dragon stump squats between our house and the stables. Legend has it the tree was so big and old that it blossomed baby dragons in the spring. Lightning struck it down long before my great grandfolks’ time. One of our favorite pastimes is to sit together on the huge stump of the evening and watch the sky ignite.

I love star-watching but have to be careful. Even when I was a kid, if I stared at the heavens too long, the sky would start to turn. It was as if I could feel the world spinning. I’d grab anything I could – a tree, boulder, weeds – to keep from being flung off the planet. Now I hold on to Jezzie. Sometimes when it happens, my wife thinks I’m being romantic. I’m embarrassed tell her the truth.

The foals kick free from their pods during the next few weeks. They’ll remain on the vine until separation in a couple months. That’s when Jezzie and I will begin the busiest period of the season – feeding, watering and exercising a dozen horses.

At least I hope a dozen survive. As Jezzie and I feared, Eleven and Twelve are too close together. Another week’s growth and their kicking hooves will be within reach of each other’s heads. One or both animals will likely be killed by its sibling. When faced with this complication a couple years back, we roped together the legs of the adjacent foals. But that sparked panic which caused both to die of heart failure.

“Eleven’s the runt,” Jezzie says, “and Twelve looks to be the finest in seasons. I say we move Eleven.”

I know my wife’s right. Twelve clearly is the superior animal and shouldn’t be put at risk. But there’s something about Eleven’s eyes. I’ve never seen such recognition in a foal on the vine. Not in a mature horse for that matter. To chance dousing that light is more than I can bear, and I know I can’t go through with it. “OK, Jezzie,” I say, stroking the white star patch on the black filly’s forehead with my thumb. “We’ll transplant her tomorrow.” I swallow hard to clear the lie from my throat.

I sneak out of the house in the middle of the night. I’m lucky there’s a full moon to work by. In the garden, I sever Twelve’s tendril from the vine. I hope Jezzie forgives me.

Whispering assurances in the colt’s ear and cradling my hand over his snout to muffle the whinny, I carry the young mustang a few paces, lower him to the ground and work the tendril into the soil. Separated from the main vine, we’ll need to hand feed and water Twelve several times a day.

As I’m finishing the transplantation, I see a shape slinking around the house. I fear it could be a coyote. A couple seasons back, rabbit pines, desirable as wind breaks, were over-planted. Though many folks recognized the problem and cut down their hare trees after the autumnal drop and hop, not enough people did the responsible thing. So farmers were encouraged to grow coyote vines. Now the rabbit problem is under control, but there are too many coyotes. At least the spike in their population will be temporary.

I stamp my feet, wave my arms and shout in the direction of the approaching silhouette. I scare whatever it is away… and awaken Jezzie. To make matters worse, Twelve has kicked his tendril out of the ground.

“Let me help,” my wife says and hurries toward me. When she sees I’m transplanting Twelve instead of Eleven, she hesitates but strokes the foal to calm it as I work the tendril more securely into the ground.

“I thought we were going to move Eleven, Jemery. I can’t believe you’d deceive me.”

I look away. Jezzie doesn’t say anything else. Not then and not for several days.

Even though you learn to move on from death when you farm horses, it’s a terrible thing to lose a member of the crop. Twelve would’ve stood a better chance if I hadn’t attempted a rushed, sneak-transplant, if I’d taken my time and enlisted Jezzie’s help. At least Eleven and the other 10 foals thrive.

It’s a special day when we separate the foals from the vine and watch them transform unsteady steps into galloping freedom. When I see Jezzie smiling, I put my arm around her. She leans toward me at first then pulls away. Because of my duplicity, there’s still a frost line above which nothing can grow.

Feeding, watering and exercising 11 horses while keeping the stables clean is no mean feat. It helps that we have the stream and hay trees on our property. Toiling together, we get through it again, and I sense some thawing in Jezzie’s feelings toward me. After a few months, it’s time for the most bittersweet moment of the season. The arrival of Pablo Aduren.

Churning up a cloud of dust, Pablo’s truck pulls a long trailer onto our property. The engine clanks, brakes squeak, and out hops Pablo. He’s rail-thin, with hair thick and black as it was a decade ago. He bangs down the ramp to the trailer. “I hear you lost one this season,” I hear him say as I head for the stable.

“A fine one it would’ve been,” Jezzie says. I can’t tell whether the comment’s meant as a dig at me.

I lead One out of the stable and toward the trailer. When we get to the ramp, he rears and snorts. I pull gently on the rope I’ve looped around his neck. “Easy, boy. Nothing to fear.” He rises again and knocks me to the ground. Hearing Jezzie shout for me to look out, I roll clear of One’s stomping hooves.

Pablo grabs the rope with one hand and helps me to my feet with the other. “Too bad we can’t make them understand,” he says.

Just then Eleven trots from the stable. She positions herself in front of One and stares into his eyes. The horse nickers, and his nostrils relax. He clomps up into the trailer.

Eleven stands beside the ramp as Jezzie and I take turns loading the rest of the crop. When it’s Eleven’s turn, she paws the ground then trots back to the stable. I look at my wife.

“Let’s keep her,” Jezzie says. “She’s unique.”

Pablo clangs the ramp into the trailer.

I ask him where they’re headed.

“The herd on the northern pass is getting a bit thin,” he says. He gives Jezzie a bag of coins. Our pay isn’t much but is ample for the little we require.

Jezzie counts the coins. “This is for 11. We gave you only 10.”

“Guess I shouldn’t have filled out the paperwork ahead of time,” Pablo says, grinning. “Seriously, you folks do so much for the herds. Consider this a bonus.”

When Pablo fires up his truck, it backfires and I hear whinnies. I’m glad the northern pass isn’t too far away. Once the horses are there, they’ll never be cooped up or restrained again.

Jezzie and I rest up for a few days then get back to work. We repair a leak in the roof of the house and replace a few rotten sideboards in the stables. My wife ensures our old beater pickup is in running condition. We go to town, stock up on produce and replenish the up-ground cellar. We clean up the horse garden and prep the soil for the next growing season. And we both chop chop chop firewood to be ready for the bite of winter. All the while Eleven runs to her heart’s content.

One morning before the first snow, I’m awakened by Jezzie shouting in the stable. Fearing something horrible, I rush to my wife and find her rubbing Eleven’s shoulders where two nubs have appeared.

Jezzie beams. “She’s birthing wings!”

I can’t believe my eyes. It’s rare, but known to occur. “See, Jezzie? As hard as it was to lose Twelve, aren’t you glad now I saved Eleven?”

My wife’s lips straighten. “I’m happy you rescued Eleven, but you went behind my back.”

“I’m so sorry I hurt you.”

“I wasn’t hurt exactly. More disappointed. We’ve always been truthful with each other.”

I feel as if a horse has kicked me in the stomach, and vow to never again be dishonest with my wife.

That evening we’re sitting on dragon stump star-watching when the sky begins turning. I put my arm around Jezzie and squeeze. She leans toward me and kisses my neck. I say I’m holding her so the spinning world won’t fling me away.

“That’s sweet,” Jezzie says.

“I mean I actually feel as if -”

She kisses my mouth, her tongue licking away my words, then takes my hand and leads me into the house. I figure she’ll understand if I wait until morning to explain.

As soon as dawn awakens us, I describe in detail what happens to me, concerned she’ll think it’s silly.

“I promise,” she says, “that as long as I’m alive you can count on me to keep the world from -”

I kiss the rest of the words from her lips.

Over the next couple months, Eleven grows white wings, spectacular on her black frame. I think we love watching her fly almost as much as she enjoys soaring. Sometimes I wonder what it would be like to see the world from on high. But I’d have to climb onto Eleven’s back, and who could be so cruel as to ride a horse?

She was night-gliding a while back. Jezzie and I were on dragon stump and saw Eleven silhouetted against the full moon. It’s a sight that’ll stay with me until I die.

I’m not sure how we got by before Eleven. One year there’s a drought. Our well barely has enough water for Jezzie and me, and the stream dries up. Eleven leads us to a spring we didn’t know about. She must’ve seen it glinting in the sunlight during one of her sky sojourns.

Another year there’s a flash flood. Eleven awakens Jezzie and me by pounding her hooves on the roof then gets the foals to higher ground.

Even during those rare seasons when nothing goes wrong, Eleven provides my wife and me with companionship and the joy of her flight. There’s never another Eleven. The temporary designations for all harvests after Eleven are One through Ten, Twelve and Thirteen.

As I said, seasons when nothing goes wrong are rare. Eleven’s buried behind where the stables stood. There’s also a grave for Jezzie and me. My wife’s already there. Lightning set fire to the stables last season. The three of us got the foals out, but the smoke overcame Jezzie, the ordeal Eleven’s heart. Because the mare’s wings were badly burned, I try to tell myself her passing was for the best. I don’t tell myself anything about losing Jezzie because there are no words.

I turned down Pablo Aduren’s offer to help me rebuild the stables. Maybe I have the strength and stamina for growing horses alone, but the will is gone. Jezzie and I put aside a few coins each season, and I’ve enough to get by.

I spend most evenings on dragon stump. Sometimes I close my eyes and imagine Jezzie is beside me watching Eleven wing past a full moon. Sometimes I stare into the sky until everything starts to turn, and I feel as if the spinning world is about to fling me to the stars. I’m ready.