2028-2031

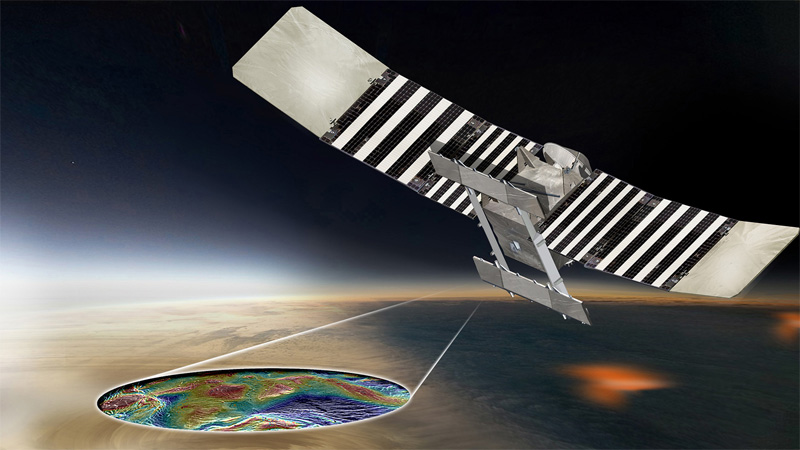

VERITAS mission to Venus

While several more recent spacecraft had used Venus to perform gravity assists, it had been decades since Magellan – NASA’s last dedicated mission to orbit and study the planet – which launched in 1989 and operated until 1994. After this long gap, the agency had been keen to update its knowledge of Earth’s twin.

Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography, and Spectroscopy (VERITAS) is a three-year mission conducted by NASA to study Venus in higher detail than ever before. In June 2021, it became one of two Venus missions selected for NASA’s Discovery Program in the late 2020s and early 2030s, the other being the DAVINCI+ probe.*

VERITAS produces global, high-resolution topography and imaging of Venus’ surface and generates the first maps of deformation and global surface rock type, thermal emissivity, and gravity field. It provides a more accurate estimate of Venus’ core size and information about features that lie below the planet’s surface, such as fault lines.

The combination of topography, near-infrared spectroscopy, and radar image data provides new knowledge of Venus’ tectonic and impact history, gravity, geochemistry, the timing and mechanisms of volcanic resurfacing, and the mantle processes responsible for them. VERITAS also reveals insights into Venus’ wetter and cooler past. Much of the probe’s data is of relevance to exoplanet science and understanding how planets beyond our Solar System evolve.

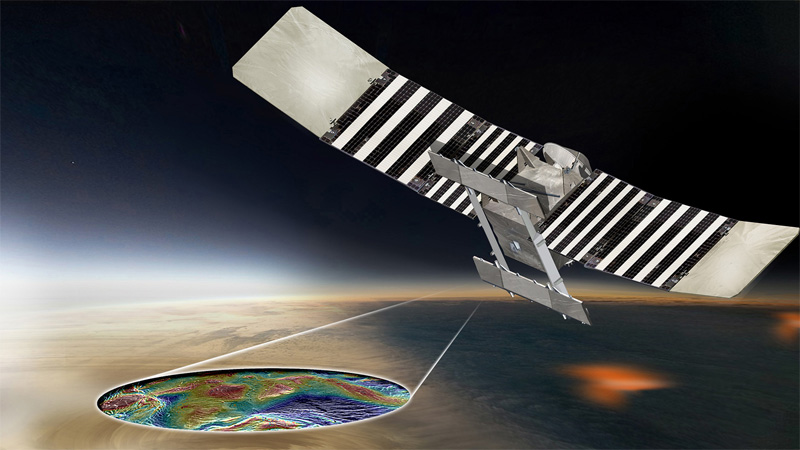

While the earlier Magellan probe had a spatial resolution of 200 m, VERITAS can generate image details as fine as 30 m, a nearly seven-fold increase.* Meanwhile, altimetry measurements are improved by as much as 60 times. On board are two scientific instruments – the Venus Emissivity Mapper (VEM) and the Venus Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (VISAR). The spacecraft operates until 2031.

Simulated comparisons of Magellan and VERITAS imaging/topographic resolutions, based on terrestrial data (Hawaii, left; and Iceland, right).

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

2028-2030

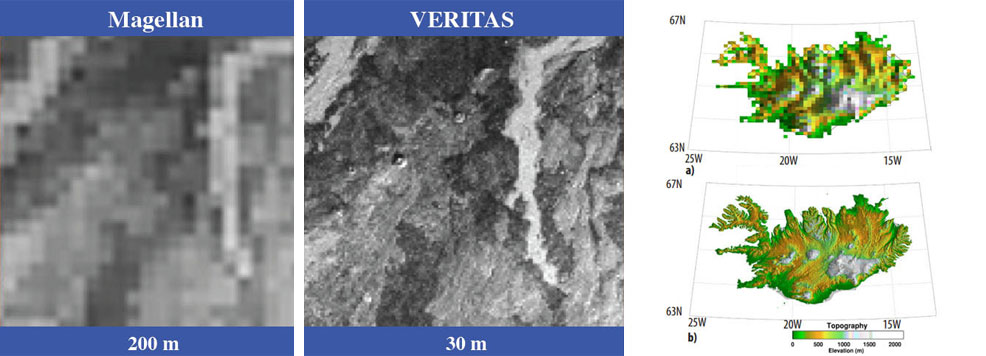

The Orbital Reef is operational

The Orbital Reef is a low Earth orbit (LEO) space station designed by Blue Origin and Sierra Nevada Corporation,** intended for commercial space activities and space tourism uses. Several other partners are involved, including Arizona State University, Boeing, Genesis Engineering Solutions, and Redwire Space.

Blue Origin, Sierra Nevada Corporation and their partners announced preliminary plans in October 2021 – just a few days after the revealing of a similar project called Starlab, being developed by a different set of companies. While Starlab had a volume of 340m³ and support for up to four people, the Orbital Reef’s design featured a much larger internal space of 830m³, supporting up to 10 occupants in futuristic modules with huge windows.

Its large size would allow the Orbital Reef to host a wide range of activities, such as scientific research, industrial manufacturing, exploration system development and exotic hospitality. The zero G environment and access to a vacuum could also provide filming opportunities for advertising and movies.

The space station flies in a 500 km (310 mi) orbit, slightly above the International Space Station (ISS). The latter is reaching the end of its lifespan as the 2020s draw to a close. NASA had extended its retirement date from 2024 to 2028 and then again to 2030. The agency is now preparing for a transition to a commercial replacement with lower costs, more flexibility, and improved technology. Blue Origin used its recently developed heavy-lift orbital launch vehicle – the New Glenn – for assembling the Orbital Reef’s core modules and utility systems. The remaining structures are now being fitted as the station becomes fully operational. Together, the Orbital Reef and smaller Starlab are able to fully replace the internal volume of the ISS, with funding from NASA.*

In addition to the station itself, a new suitless “Single Person Spacecraft” has been developed by partner Genesis Engineering, as an alternative to traditional spacesuits used during spacewalks. Those who visit the Orbital Reef can take advantage of this pod-like craft with its greater manoeuvrability, two robotic arms and larger field of view.**

Credit: Blue Origin

2028

China’s economy surpasses that of the U.S.

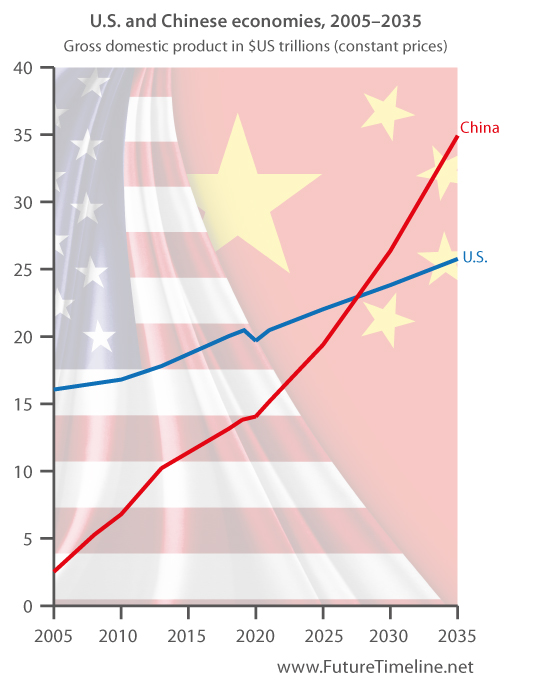

In 2028, China overtakes the United States in gross domestic product (GDP) and becomes the world’s largest economy. This milestone has occurred earlier than some expected, due in part to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The virus responsible for COVID-19 had first been identified in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. It spread rapidly, helped by the Chinese New Year migration and Wuhan being a transport hub and major rail interchange. With cases growing exponentially, major disruption began to emerge in early 2020 and many Chinese cities went into lockdown. As the virus spread to other countries, the World Health Organization declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern in January and a pandemic in March 2020.

Initially, COVID-19 had been a major crisis for China. However, its authoritarian government imposed strict measures throughout the country, allowing it to bring the outbreak under control by the second quarter of 2020. While many berated the Chinese government for its delayed response and censorship of related information during the opening stages of the outbreak, few would doubt the success of China in essentially defeating the virus.

By contrast, most other countries around the world had lengthy and catastrophic experiences with COVID-19, wreaking severe economic damage. The U.S. recorded its millionth case by April 2020 and this had mushroomed to over 23 million by January 2021, with nearly 400,000 deaths, the most of any country. Although vaccines began to emerge, partisan divides regarding the outbreak and a laxer approach to preventing infections meant that the crisis would persist for many months to come.

The U.S. and other major economies had negative growth for the year, while China achieved positive GDP growth of 2% in 2020. China’s 14th Five Year Plan (2021-25) involved a “dual circulation” strategy, with plans for both external and domestic demand working together. This had been implemented partly in response to trade disputes with the U.S. and elsewhere, and partly due to expectation that external demand would be depressed by the pandemic and that China needed internal demand to sustain growth.

President Xi stated his aim as being to “fully bring out the advantage of its (China’s) super-large market scale and the potential of domestic demand to establish a new development pattern featuring domestic and international circulations that complement each other.”

With skilful management of the pandemic and damage to long-term growth in the West, the relative economic performance of China exceeded many analysts’ earlier forecasts. China saw average economic growth of more than 5.5% a year during this time. By the end of its 14th Plan period in 2025, it had comfortably met the threshold for a high-income economy, defined by the World Bank as a gross national income per capita of US$12,536 or more.

Although its growth has slowed to 4.5% a year during the second half of the 2020s, China’s GDP is overtaking the U.S. by 2028.** It continues to widen the gap between itself and the U.S. during the early 2030s, though at a slower rate of less than 4% a year. Longer-term demographic and other problems in China enable the U.S. to regain its position as the world’s largest economy by the end of the century.

Medical marijuana is legal in the majority of countries

The Cannabis plant had a long history of medicinal use, dating back thousands of years. Its usage remained controversial and taboo in many cultures, however. Not until the late 20th and early 21st century did it start to gain wider acceptance and legality as an option for treating health issues.

Due to production and governmental restrictions, little research had been conducted into the safety and efficacy of cannabis for medicine. A systematic review and meta-analysis in 2015 found moderate-quality evidence in support of treatment for chronic pain and spasticity, but lower quality evidence of improvements in nausea and vomiting due to chemotherapy.*

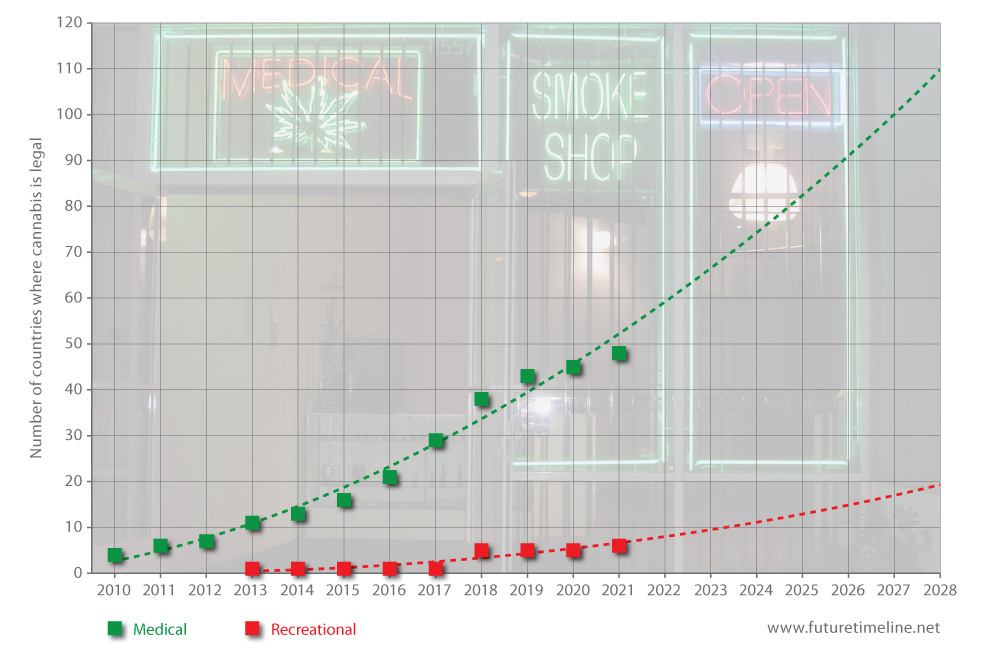

A number of medical organisations around the world called on governments to better enable scientific study of these drugs. Amid growing support for reviews of its legal classification, more and more countries began to decriminalise cannabis and enable its usage for medical reasons. Some even permitted recreational use in limited amounts. Uruguay became the first country to legalise the whole process from cultivation, to sale, distribution, and consumption. Nearly 20 states in the United States had legalised recreational use by 2020, though it remained illegal at the federal level.

Public opinion polls reflected this ongoing trend. In 1990, almost 80% of U.S. adults believed that marijuana should be illegal. By 2020, that figure had declined to just 32%. The strongest support came from Millennials – an increasingly influential voting bloc – with 76% in favour of legalisation compared with 63% for Boomers and just 32% for the Silent Generation.*

By 2028, the majority of the world’s countries allow cannabis-derived treatments for medical use. A total of 45 countries had made it legal by 2020* and this figure is now approaching 110. The products can be administered through a variety of methods, including capsules, lozenges, tinctures, dermal patches, oral or dermal sprays, cannabis edibles, and vaporising or smoking dried buds. The global medical cannabis market size is undergoing a compound annual growth rate of 23% during this decade. Valued at $6.8 billion in 2020, it reaches $53.9 billion by 2030.*

The number of countries allowing recreational use of marijuana has also increased, though at a slower rate. From just five in 2020, it has quadrupled to nearly 20 by 2028 – but will not reach a majority until the 2050s.

Background image credit: Laurie Avocado (CC BY 2.0)

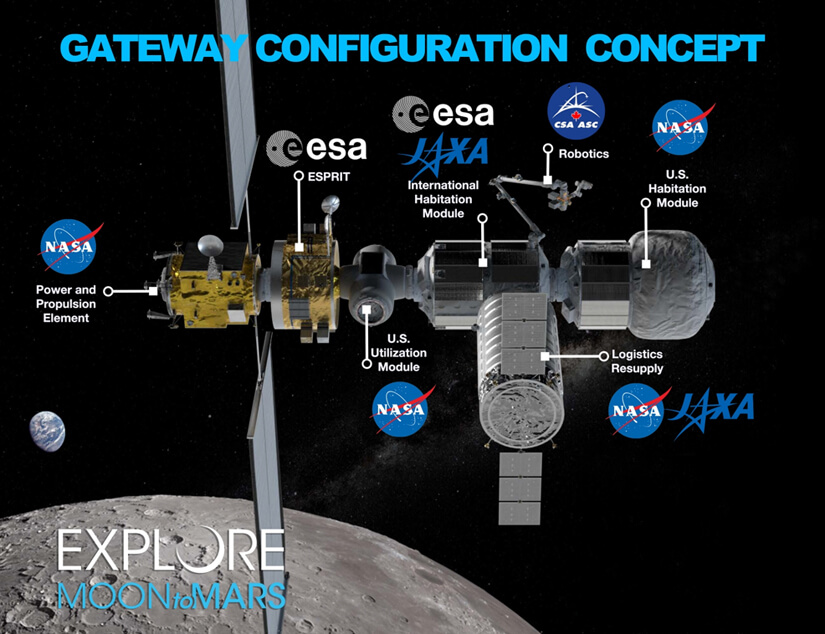

Completion of the Lunar Gateway

The Lunar Gateway (LG) is the successor to the aging International Space Station (ISS). Whereas the ISS was placed in orbit around the Earth, the LG is close to the Moon. The partners involved in its construction are similar to the ISS: the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), European Space Agency (ESA), Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), and NASA.

The Gateway is developed, utilised and maintained in collaboration with commercial and international partners as a “staging ground” for lunar surface operations (both robotic and crewed) and for eventual travel to Mars. By sending people and cargo to and from cislunar space, those involved in the project gain the knowledge and experience necessary to venture to the Moon and beyond.

Originally, NASA had intended to build the Gateway as part of an “Asteroid Redirect Mission”, but later cancelled this plan. An informal joint statement on cooperation between NASA and Roscosmos was announced in September 2017. However, in October 2020, Roscosmos stated that the program would be too “U.S.-centric” for Russia to participate in, and in January 2021 confirmed that it would not take part in the LG. NASA commissioned studies by private companies into affordable ways to develop the station’s power and propulsion elements – these private companies were Boeing, Lockheed Martin, Orbital ATK, Sierra Nevada and Space Systems/Loral.

The LG would be built in stages. Originally, the plan had involved each part being delivered solely by the Space Launch System (SLS), a huge new rocket being developed by NASA. However, a subsequent plan incorporated commercial launch vehicles, such as the SpaceX Falcon Heavy. The latter would also carry supplies to the LG using a new craft called the Dragon XL – similar to the commercial cargo program for the International Space Station – to support crewed missions there and to the lunar surface.

The international partners involved in the LG planned for its construction to occur gradually from 2024 to 2028, with delivery of four main components:

• Power and Propulsion Element (PPE) – serving as the main command and communications centre of the LG, the PPE can generate 50 kW of solar electric power for its ion thrusters, which can be supplemented by chemical propulsion. An S-band communication system provides a radio link with nearby vehicles and it can also function as a space tug, transferring a spacecraft from one orbit to another. Alongside the Habitation and Logistics Outpost (see below), the PPE is the first component of the LG to be delivered, launched by SpaceX on a Falcon Heavy in 2024.

• Habitation and Logistics Outpost (HALO) – a crew cabin for astronauts visiting the LG. Its primary purpose is to provide basic life support needs for the visiting astronauts and to enable preparation for trips down to the lunar surface. In addition to environmental controls and energy storage, it features space for science and stowage, data handling capabilities, and docking ports for visiting vehicles and future modules. The HALO is delivered in 2024.

• International Habitation Module (I-HAB) – an additional habitation module, built by ESA in collaboration with Japan. Together, the I-HAB and HALO provide a combined 125 m³ (4,400 cu ft) of habitable volume for the station. Delivery of the I-HAB occurs in 2026. This component also includes a large robotic arm contributed by Canada’s space agency.

• European System Providing Refuelling, Infrastructure and Telecommunications (ESPRIT) – a service module with an airlock for science packages, additional capacity for xenon and hydrazine propellant, and communications equipment. It also features docking ports and a small windowed habitation corridor. The ESPRIT module consists of two parts and is fully installed by 2027.

The complete assembly of the Lunar Gateway requires about 25 launches from Earth, most of which are uncrewed. The final delivery occurs in 2028* and the station then begins full operations, serving as a platform for missions down to the Moon. These surface operations are initially robotic but enable construction of a permanent human base in the 2030s.

The LG has an expected service time of about 15 years, allowing it to operate into the early 2040s. Towards the end of this period, NASA begins testing a new and separate vehicle designed for crewed missions to more remote destinations, such as Mars. Known as the Deep Space Transport (DST), this can carry up to six astronauts on extended voyages, using both electric and chemical propulsion. The DST is returned to the LG after each mission to be serviced and reused for a new mission.

Overall, the Lunar Gateway lives up to its name as a “gateway” to places beyond low-Earth orbit (LEO) and is arguably the logical next step for human exploration of space. In addition to being a platform for regular visits to the lunar surface and functioning as a relay between the Earth and Moon, it also provides opportunities to test new technology for reaching Mars.

Launch of the European ATHENA X-ray observatory

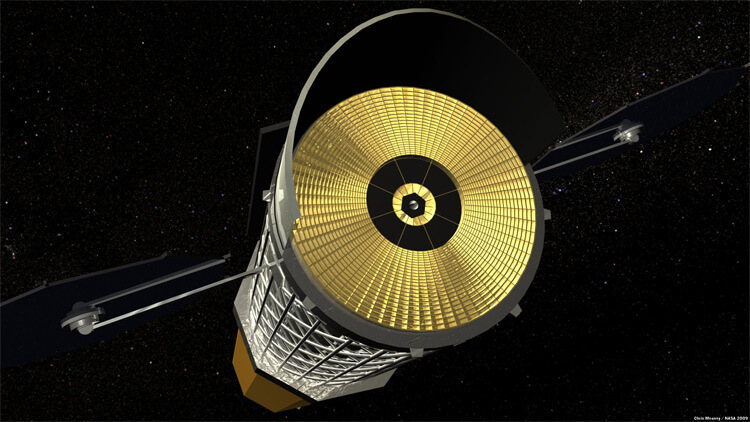

The Advanced Telescope for High ENergy Astrophysics (ATHENA) is a major new X-ray telescope launched by the European Space Agency.** This L-class (Large) project is the second of three missions in the “Cosmic Vision” programme which includes two other spacecraft – the Jupiter Icy Moon Explorer (JUICE) launched in 2022 and a gravitational wave observatory being deployed in 2034.

X-ray observations are crucial for understanding the structure and evolution of stars, galaxies and the Universe as a whole. These images can reveal “hot spots” in the Universe – regions where particles have been energised or raised to very high temperatures by strong magnetic fields, violent explosions, and intense gravitational forces. X-ray sources are also associated with the different phases of stellar evolution such as supernova remnants, neutron stars and black holes.

ATHENA is designed to answer a number of important questions in astrophysics:

• What happens close to a black hole?

• How did supermassive black holes grow?

• How do large-scale structures (i.e. galaxy clusters and superclusters) form?

• What is the connection between these processes?

To address these questions, it can trace orbits close to the event horizon of black holes, measure black hole spin for several hundred active galactic nuclei (AGN), use spectroscopy to characterise the outflows and environments of AGN at their peak activity, look for supermassive black holes out to redshift z = 10, map the bulk motions and turbulence in galaxy clusters, find missing baryons in the cosmic web using background quasars, and observe the process of cosmic feedback where black holes inject energy on galactic and intergalactic scales.

This enables astronomers to understand better the history and evolution of matter and energy – visible and dark – as well as their interplay during the formation of the largest structures in the Universe. Closer to home, observations constrain the equation of state in neutron stars, black hole spin demographics, when and how elements were created and dispersed into the intergalactic medium, and much more.

To achieve these goals, ATHENA requires a collecting area of 3 square metres with 5 arcsec angular resolution and 12 metre focal length, for unmatched sensitivities. Relative to previous X-ray missions, it offers a 100-fold increase in the area for high resolution spectroscopy, deep spectral and microsecond spectroscopic timing with high count rate capability. It also features a large shield that blocks light from the Sun, Earth and Moon, which otherwise would heat up the telescope and interfere with observations. The telescope remains operational until the late 2030s.

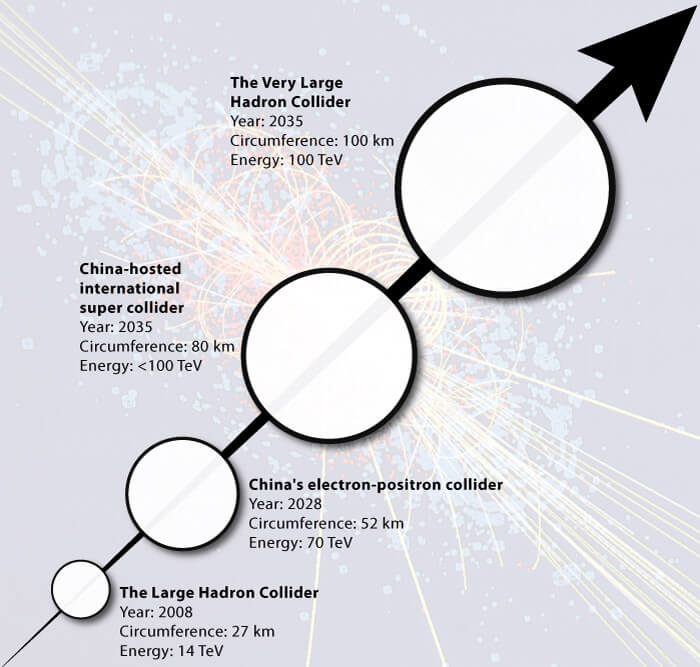

China builds the world’s largest particle accelerator

Following the success of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) in Europe,* the Chinese decided to build their own larger particle accelerator. Researchers at the Institute of High Energy Physics in Beijing announced plans for a machine 52 km (32.5 mi) in length – twice the circumference of the LHC. This would allow the Higgs boson to be studied in greater detail, revealing new insights into the fundamental structure of matter and confirming whether multiple types of Higgs boson existed. Construction began in 2019, with completion in 2028.* It paves the way for an even larger project in 2035.**

British newspapers are going out of circulation

By the late 2020s, the last of Britain’s national newspapers are being taken out of circulation.* Even once formerly major titles like the Sun, the Daily Mail and the Daily Mirror have ceased production. The surviving newspapers have now all transitioned to entirely digital formats.

The printing industry had a long history in Britain. The first printing press was invented by William Caxton in 1476. This led to further developments in mechanical movable type and a huge increase of printing activities over subsequent centuries. During the 1600s, various publications would spread both news and rumours – such as pamphlets, posters and ballads. The English Civil War (1642–1651) greatly increased the demand for news.

Among the first real “newspapers” were the Oxford Gazette (1665), Berrow’s Worcester Journal (1690) and Daily Courant (1702). By the 1720s, there were 12 London newspapers and 24 provincial papers. The first English journalist to achieve national importance was Daniel Defoe (1660–1731). During the 18th and 19th centuries, the Industrial Revolution allowed production methods to be improved, print runs to be greatly increased and newspapers to be sold at lower cost. Circulation of The Times rose from 5,000 copies in 1815 to 10,000 in 1834 and 40,000 by 1851; about 80% of the entire market.

The period from 1860 to 1910 was considered a “golden age” of newspaper publication, with further technical advances in printing and communication – combined with a more professional style of journalism and the prominence of new owners. Socialist, labour and trade union papers began to proliferate. In 1896, The Daily Mail was first published and became the first daily newspaper aimed at the newly literate “lower-middle class market resulting from mass education, combining a low retail price with plenty of competitions, prizes and promotional gimmicks.” It was the first British paper to sell a million copies a day. Two other “halfpenny” papers to emerge included the Daily Express and the Daily Mirror. By the 1930s, over two-thirds of the population was estimated to read a newspaper every day, with almost everyone taking one on Sundays.

Circulations continued to increase, reaching a peak in the mid-20th century. From the 1960s onwards, however, sales began to decline. In an effort to attract more readers, some tabloids – including The Sun, the Daily Mirror and Daily Star – began publishing images of topless women. The 1980s saw the introduction of computer-based typesetting and full-colour offset printing. The reporting of stories became ever more sensationalised and controversial as the fall in sales continued through the 1990s and into the 21st century.

The rapid rise of the Internet – providing instant and free access to information – accelerated the decline of the newspaper industry. A major factor was the emergence of smartphones, tablets and other handheld, web-enabled devices, becoming cheap and widely available. By 2015, none of the remaining UK papers had a daily circulation above two million. The overall circulation of newspapers declined by 6.6% in 2014–15, with further declines in the following decade, resulting in the end of printed national newspapers in Britain.

Launch of the Comet Interceptor

Comet Interceptor is a mission by the European Space Agency (ESA) to rendezvous with a comet originating from the outer Solar System that has now begun to approach the Sun. This follows a similar effort – Rosetta – that visited 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko in 2014. However, unlike that earlier probe, this new craft is designed to encounter a “pristine” comet with largely undisturbed material surviving from the dawn of the Solar System. The targeted body is therefore an ‘Oumuamua-like interstellar object, or possible fragment from the Oort cloud, approaching the inner Solar System for the first time, as opposed to a short-period comet like 67P that orbits the Sun every six years.

The mission is unusual, in that it launches before a primary target has even been found. For a dynamically-new comet (DNC) or interstellar object, the time between discovery, perihelion and departure from the inner Solar System – typically a few months to a year – is too short for mission organisers to prepare and launch a new spacecraft. As such, these astronomical objects can only be encountered after being discovered inbound, with enough warning to direct an already operating spacecraft to approach. However, new observatories, such as the recently completed Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, are now improving this time by covering large areas of sky more deeply and rapidly.

The spacecraft is separated delivered to Lagrange point L2 via its own propulsion system. Comet Interceptor consists of a mothership and two smaller “daughters”, which perform simultaneous observations from multiple angles to generate a 3D profile. The daughter probes carry instruments on different trajectories through the comet’s tail, while also getting close to the nucleus. Together, all three spacecraft greatly improve the understanding of pristine comets and their surrounding environment, revealing their structures and compositions in more detail and their dynamic nature as they interact with the solar wind. This, in turn, provides new insights into the conditions that existed at the birth of the Solar System and perhaps even further back in time.*

Credit: Brooks Bays / SOEST Publication Services / University of Hawaii

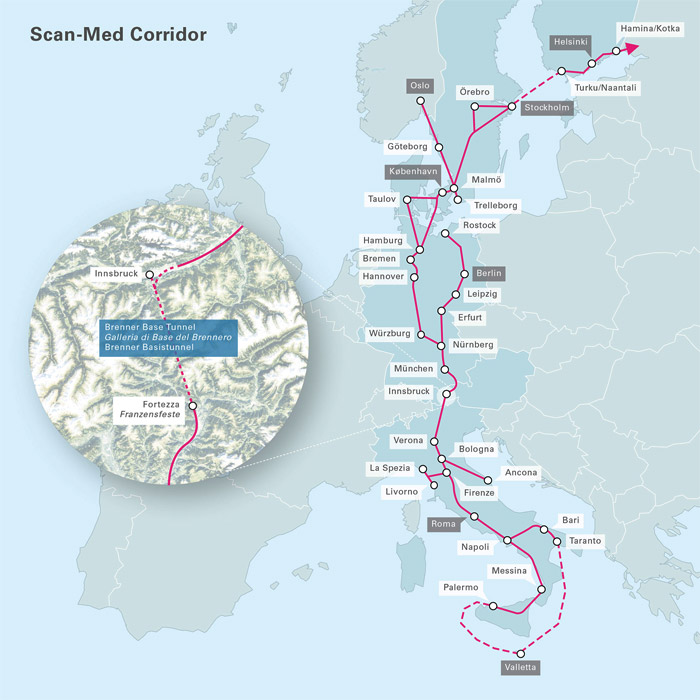

Completion of the Brenner Base Tunnel

The Brenner Base Tunnel is a 64 km (40 mi) freight and passenger train route, running through the base of the Eastern Alps mountain range and linking Scandinavia with the Mediterranean. It consists of two primary tunnels, carrying traffic from north to south (and vice versa). A smaller secondary tunnel lies below these and is used during construction as a guide tunnel to determine geological conditions, then later used for drainage and emergency access.

The €9.2bn ($11bn) project receives substantial funding from the European Union (EU). It forms the central component of the gigantic SCAN-MED Corridor – beginning in Finland and running all the way down to Malta – which forms a crucial north-south axis for the European economy.

In addition to the Brenner Base Tunnel in central Europe, another major component of the SCAN-MED Corridor is the Fehmarnbelt Fixed Link in the northern part of the route. This undersea tunnel provides a direct link between northern Germany and Lolland, and from there to the Danish island of Zealand and Copenhagen, becoming the world’s longest combined road and rail tunnel. The Fehmarnbelt Fixed Link is completed shortly after the Brenner Base Tunnel.

Credit: bbt-se.com

Maximum operating speeds in the Brenner Base Tunnel are 250 km/h (155 mph) for passenger trains and 160 km/h (99 mph) for freight trains. This helps to relieve a major bottleneck on the alpine connections between Germany and Italy.

Previously, journeys had involved meandering rail and congested roads with steep inclines. By contrast, the Brenner Base Tunnel is an entirely new route passing smoothly and directly through tens of kilometres of rock. At a depth of 1,720 m (5,640 ft) below the surface, it becomes the lowest passage through the Alps – cutting travel times from 80 to just 25 minutes.

A major technical challenge had been the four distinct rock types and one of Europe’s longest fault lines, through which the tunnel would need to pass. Phase I lasted from 1999 until 2002 and involved preparatory work. Phase II followed from 2003 to 2008 with prospection borings, environmental planning and the final technical details. The construction phase of the main tunnel began in 2011.

The project involves a total of 21.5 million cubic metres of material being excavated, with around one-third of this being recycled and reused as concrete aggregate in the tunnel. The remaining material goes to five sites above ground, acting as filler for areas that can be reforested and landscaped. When completed in 2028, the Brenner Base Tunnel becomes the longest underground railway connection in the world, surpassing the 57 km (35 mi) Gotthard Base Tunnel.*

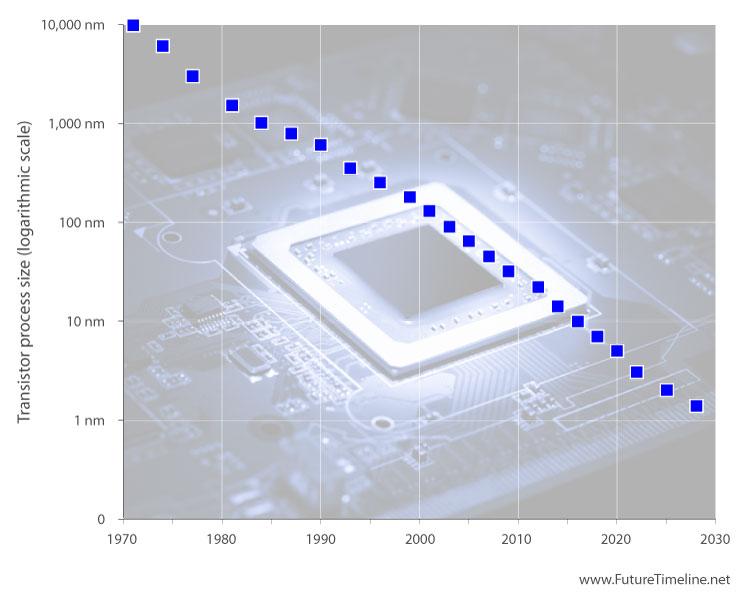

1.4 nm nodes begin mass production

In semiconductor manufacturing, the 1.4 nanometre (nm) process is the next die shrink following the 2 nm process node. In recent years, the names of these process nodes have become more of a marketing term, as opposed to the actual dimensions of components. Nevertheless, this latest generation enables a further advance in miniaturisation and the cramming of ever more transistors onto computer chips.

In 2022, Apple released the M1 Ultra system-on-a-chip, with 114 billion transistors. By 2028, the first consumer-level CPUs and GPUs with 1 trillion transistors are becoming available, a nearly ten-fold increase in density.* These improvements also come with reduced power consumption.

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) and Samsung had both announced their intention to begin volume production of 3 nm in 2022 followed by 2 nm in 2025. TSMC revealed plans for a 1.4 nm process by 2028,* while U.S. chipmaker Intel planned to achieve this by 2029.

These and other companies have been researching new methods of scaling down – such as graphene nanomesh and nanoroad transistors and improvements in extreme ultraviolet lithography (EUVL). The challenge of miniaturisation is becoming so great that a radical new paradigm may soon be needed to maintain the trend in computing power.

Delhi becomes the most populous city in the world

By 2028, Delhi has overtaken Tokyo to become the most populous city in the world. The Japanese capital had held the title since 1955, but during the early years of the 21st century it began to reach a plateau. After peaking at 37 million, the city actually went into decline from 2020 onwards. The Indian capital, by contrast, was surging ahead. Home to some 29 million people in 2018, Delhi expanded to reach 37.2 million just a decade later.** India as a whole has recently surpassed China to become the most populous country on the planet.

There are many challenges associated with rapidly growing urban areas, especially in low-income and lower-middle-income countries. These include the provision of adequate housing, transportation, water, waste management and sanitation, energy and other vital infrastructure, as well as employment and basic services such as education and health care. However, India’s workforce is young and dynamic; its economy is expanding fast and on course to rival the other major superpowers by 2040.

One surprising area in which Delhi will soon benefit is the environment. For many years, the World Health Organization had ranked Delhi as the most polluted city on Earth. In the 2010s, poor air quality was causing 2.3 million deaths in India each year – almost the same as from tobacco use – costing 3% of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). However, towards the end of the 2020s, traditional petrol and diesel cars are being phased out, in favour of electric vehicles.* Widespread use of solar and other renewables is also making a difference now, with almost 60% of India’s electricity being generated from non-fossil fuels.*

Furthermore, as part of its commitment to the Paris climate agreement, India had pledged $6.2 billion to reforest 235 million acres (95 million hectares) of the country by 2030.* This vast project will soon increase India’s forest cover from 21% of total land area to 33%.

Credit: Sean Hsu

Los Angeles hosts the Summer Olympic Games

From 21st July to 6th August 2028, the 34th Summer Olympics are held in Los Angeles, California.* This event is the fifth Summer Games to be hosted in the United States, and the third in Los Angeles – following St. Louis 1904, Los Angeles 1932, Los Angeles 1984 and Atlanta 1996. Los Angeles also becomes the third city after London (1908, 1948 and 2012) and Paris (1900, 1924 and 2024) to have hosted the Olympic Games on three occasions.

The 2028 Games are spread across four areas, each highlighting the different geographical features of the city: Long Beach, South Bay, Downtown and Valley Sports Park.* Travel between venues is made easy thanks to L.A.’s extensive system of highways and public transport, with many improvements and upgrades having been made since the 1984 Games. By 2028, $88bn worth of expanded subway, light rail, rapid bus transit, and express lane projects are operational, connecting all sports parks, the airport, the Games Centre, and every corner of L.A.

The Olympic and Paralympic Village is based at the centrally-located UCLA campus, close to the city’s cultural and entertainment attractions. All Olympic and Paralympic sports parks are within 40 minutes of the Village.

The opening and closing ceremonies are each, for the first time, staged across two different stadiums. The opening ceremony starts at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum and finishes at the Los Angeles Stadium at Hollywood Park (the latter forming part of a major new sports, entertainment, hotel and business district). The order is reversed for the closing ceremony.

While most Olympic host cities have seven years to prepare, Los Angeles was given an additional four, for a total of 11 years. This was due to the unusual bidding process in 2017, which saw Paris and Los Angeles elected simultaneously for 2024 and 2028, respectively.*

Total solar eclipse in Australia and New Zealand

A total solar eclipse occurs on 22nd July 2028.** Totality occurs in a narrow path across the Earth’s surface, with a partial solar eclipse visible over a surrounding region thousands of kilometres wide. The central line of the path crosses the Australian continent from the Kimberley region in the northwest and continues in a southeasterly direction through Western Australia, the Northern Territory, southwest Queensland and New South Wales, close to the towns of Wyndham, Kununurra, Tennant Creek, Birdsville, Bourke and Dubbo. It continues on through the centre of Sydney, where the eclipse has a duration of over three minutes. It also crosses Dunedin, New Zealand.

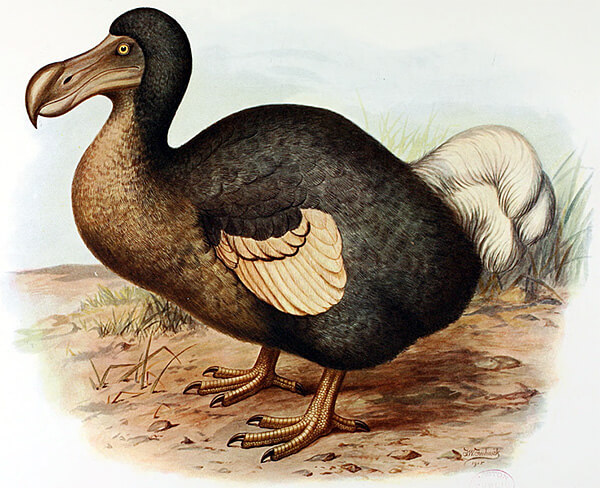

Resurrection of several extinct species has been achieved

In 2009, the Pyrenean Ibex became the first animal to ever be made “un-extinct”, for seven minutes, when a cloned female was born alive before dying from lung defects.* This was eventually followed by a woolly mammoth, using tissue samples from ancient permafrost.* By the late 2020s,* a number of other species have been resurrected (with varying degrees of success) including the famous dodo – last observed in 1662 – and the wild pigeon, Ectopistes migratorius, which went from being one of the world’s most common birds during the 19th century, to extinction in the early 20th.

Three different approaches have been taken to restore lost animals and plants:

- Cloning, in which genetic material is extracted from preserved tissue to create an exact modern copy.

- Selective breeding, where a closely-related modern species is given characteristics of the extinct relative.

- Genetic engineering, where DNA of a modern species is edited until it closely matches the extinct species.

Ethical and legal issues are now emerging, however, such as the effect of these “alien” species on modern ecosystems and the possibility of diseases. With genetics advancing at such a rapid rate, even hominids like neanderthals could potentially be brought back. Further into the future, de-extinction of lost species will become a vital part of restoring the Earth’s biosphere, as a global rewilding effort takes shape.

The final Avatar movie is released

After the success of his 1997 movie, Titanic, director James Cameron began a project that took almost 10 years to make: his science-fiction epic Avatar (2009). This was a landmark for 3D technology and CGI, with numerous accolades – winning Oscars for Best Art Direction, Best Cinematography and Best Visual Effects, and nominated for a total of nine, including Best Picture and Best Director. It also won the 67th Golden Globe Awards for Best Motion Picture – Drama and Best Director, and was nominated for two others. At the 36th Saturn Awards, Avatar won all ten awards it was nominated for.

Numerous other awards, nominations and honours were received. With a worldwide box-office gross of more than $2.7 billion, Avatar became the highest grossing film of all time – surpassing Cameron’s previous blockbuster, Titanic ($2.2 billion).

Two sequels to Avatar were initially confirmed after the success of the first film. This number was subsequently expanded to four, with Cameron said to be directing, producing and co-writing all of them. Many of the stars from the original film would reprise their roles – including Sam Worthington, Zoe Saldana, Giovanni Ribisi, C. C. H. Pounder and Joel David Moore. Despite the deaths of their characters in the original film, Stephen Lang and Matt Gerald would also make an appearance. Sigourney Weaver was confirmed too, although playing a different character.

New cast members included Kate Winslet and Cliff Curtis, portraying Na’vi “reef people”, along with Oona Chaplin as Varang, described as a “strong and vibrant central character who spans the entire saga of the sequels”. A number of child actors would also portray “free-divers” and become pivotal new characters through the sequels.

The second Avatar movie, being set in marine environments, would feature heavy use of underwater scenes, actually filmed underwater with the cast in performance capture. Blending underwater filming and performance capture was a feature never accomplished before,* requiring a year and a half to develop a new motion capture system. The film would also be shown in “glasses-free 3D”, another first in film history.

Following acquisition by Disney, these sequels were pushed back. The COVID-19 crisis caused yet further delays in production. Avatar 2 would be shifted to December 2022 (from its original December 2020 date) followed by Avatar 3 in December 2024 and Avatar 4 in December 2026. The science fiction epic reaches its conclusion with a fifth and final film released in December 2028* (three years later than its original planned date). Computing power is orders of magnitude more advanced than in 2009, making the visual effects in these subsequent films even more spectacular and impressive than the original, setting a new benchmark for CGI in movies.

![]()

Credit: Supershine