At the end of March, a book that had been condemned to die came back to life. There was no star-studded launch, and no great fanfare, although this book is now somewhat famous. The new publisher of the poet Kate Clanchy’s memoir Some Kids I Taught and What They Taught Me felt it wrong to cash in on the controversy that has engulfed it. So the new editions – with some intriguing changes to the original text – were quietly resupplied to bookshops willing to stock them.

What follows is a tale that reverberates well beyond publishing. It’s about whose voice is heard, which stories are told, and by whom. But it has broader implications for working life, too, particularly in industries where so-called culture wars raging through the outside world can no longer be left at the office door.

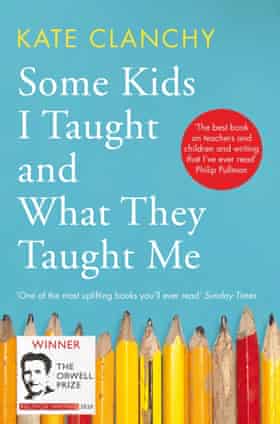

When Some Kids first emerged in 2019, Clanchy was much admired for her work at an Oxford comprehensive, teaching children from diverse backgrounds to write poetry, with sometimes luminous results. A celebration of multicultural school life, coupled with candid reflections on her own flaws, Some Kids was lauded by reviewers and won the Orwell prize for political writing, with judges praising a “brilliantly honest writer” whose reflections were “moving, funny and full of love”. But then things began to unravel.

In November 2020, a teacher posted on the amateur reviewers’ website Goodreads that the book was “centred on this white middle-class woman’s harmful, judgmental and bigoted views on race, class and body image”, using “racist stereotypes” to describe pupils. The author, she said, wrote of their “chocolate skin” and “almond eyes”.

Clanchy hit back, initially on Goodreads and then in July 2021 on Twitter, claiming “someone made up a racist quote and said it was in my book” and urging her followers to challenge reviews she said had caused threats against her. Literary giants, including the 75-year-old children’s author (and president of the Society of Authors) Philip Pullman, rose to her defence. Yet it quickly emerged that those phrases (although not, as we will later hear from Clanchy, everything attributed to her) were in the book. Her prickly response not only sat awkwardly with Some Kids’ theme of a narrator open to learning about herself – one who believed, she wrote, that deep down “most people are prejudiced; that I am, that prejudice happens in the reading of poetry as well as everything else” – but had unintended consequences for her critics, too.

Three writers of colour, Monisha Rajesh, Prof Sunny Singh and Chimene Suleyman, who had challenged Clanchy on Twitter, endured months of racist abuse and sometimes violent threats, despite Clanchy’s own publisher, Picador, describing their criticisms as “instructive and clear-sighted”. An 18-year-old autistic writer named Dara McAnulty, who had questioned Clanchy’s description of two autistic pupils as “jarring company”, was forced off social media by abusive messages. Picador, having initially apologised, saying Clanchy would rewrite the book, then announced this January that it was parting company with her by mutual consent. (She has suggested Some Kids would have been pulped had Mark Richards, co-founder of the new publishing house Swift, not bought the rights.) Clanchy, who lost both her parents and got divorced in the same year her career imploded, meanwhile disclosed in December that she had, at times, felt suicidal.

The row erupted at an anxious time for publishing, following similar pushback at novels ranging from Jeanine Cummins’s 2020 book American Dirt – whose portrayal of a migrant Mexican family was critically acclaimed, until Latin American writers accused its author (who is of Irish and Puerto Rican heritage) of peddling stereotypes and inaccuracies – to the queer black author Kosoko Jackson’s A Place for Wolves, a gay love story set during the Kosovo war that was withdrawn in 2019 at the writer’s request after Goodreads reviewers attacked his representation of Muslim characters.

The Nobel prize winner Kazuo Ishiguro has recently suggested authors are running scared of an “anonymous lynch mob” online, while the novelist Sebastian Faulks vowed no longer to describe female characters’ appearance after being criticised for doing so in the past. Debate rages over whether these are long overdue correctives, or represent the stifling of imagination; whether art has the right to offend, and whether publishing would be navigating all this less clumsily if it weren’t a predominantly white middle-class industry itself.

That Some Kids got so far without ringing alarm bells merely confirms some of its critics’ suspicions of a business employing many people like Clanchy, but few who resemble her pupils. Yet others in the industry are troubled that one writer was seemingly left to face the fallout alone, as a scapegoat for wider collective sins.

“It was a group fail,” says one veteran agent, who asks to remain anonymous. “I think the publisher failed in their duty of care to the writer. I think the author failed in her duty of care to her pupils, and in saying that she didn’t write what she did. Nobody emerges from that story well. Harm has been done, and now everyone’s afraid.”

Monisha Rajesh is in Sweden, on a train heading for the Arctic Circle, when we speak. A travel writer, she is enjoying returning to the work she loves after a stressful few months. Lots of people criticised Some Kids, she points out, including hundreds of teachers who signed an open letter questioning whether Clanchy (who carefully anonymised her pupils for publication) had adequately safeguarded them. But it was Rajesh, plus fellow writers Singh and Suleyman, who were identified as leading the Twitter charge, for what she feels were “quite obvious reasons – the angry brown people trope”. Avalanches of racist hate mail ensued. Every time the story hit the headlines, she’d log off social media or get someone else to sift her emails but, even then, she says, it was unavoidable. “I would start getting WhatsApps from friends saying, ‘Are you OK?’, and I’d think, ‘Oh God, another one.’ It preoccupies you. I’d be trying to put my kids to bed and I’d get a WhatsApp … it’s never-ending.”

As a mother of two young daughters, Rajesh was upset by the “general lack of kindness” in Clanchy’s often very physical descriptions of children; the “butch-looking” Pakistani girl with her “distinct moustache”; the Essex boy with the “Ashkenazi nose” who surprises her by denying he has Jewish roots; the white girls from council estates whom she deems not pretty, or destined to end up fat like their mothers. The text is peppered with references to children’s “Somali height”, “Cypriot bosoms”, or one star pupil’s “Mongolian ferocity”. But something about it also stirred painful memories from Rajesh’s own schooldays.

“I had teachers like her,” she says quietly. “I had teachers who did absolutely put me to one side as being the small child with the furry eyebrows or the ’tache and they made you feel like outsiders – without necessarily meaning to do it, but they did. And it didn’t matter how well meaning they were, it did make you feel small and it troubled you later in life.”

She rejects accusations of trying to “cancel” Clanchy as a writer. “You’re not being cancelled, you’re being challenged. You’re not used to being challenged, and, now you are, you don’t know what to do about it. And it’s only going to happen more now that marginalised readers and editors feel more empowered. All it boils down to is: please stop writing about us like this.”

In the book, Clanchy writes indignantly about how her pupils lost out to white children in the judging of literary prizes, or rarely saw themselves represented in books; her supporters point to her years of advocacy for marginalised youngsters whose poetry she published in anthologies. But for Rajesh, the implication that a “good liberal” couldn’t have erred feels shortsighted. “The narrative started to swing towards: ‘But this wonderful woman who’s done this wonderful stuff with children’s poetry – how on earth could you possibly fault someone like that?’ and I felt it was a real blind spot.” The row wasn’t even about Clanchy personally, she says, so much as what publishing was enabling.

For many of its critics, Some Kids crystallised deeper frustrations with an industry avowedly keen to change, yet seemingly slow to do so. Publishing has moved on since the days when, in one agent’s words, “everyone was called Sebastian”. In March, the Publishers Association announced its target for 15% of staff to come from ethnic minority groups had finally been met. And while a 2016 survey by the trade magazine The Bookseller found fewer than 100 of the thousands of books published that year were written by people of colour, research for the Publishers Association suggests that number may now have risen.

Nonetheless, suspicions persist that, as one novelist of Asian heritage puts it, it’s still easier for white people to get published writing about minority communities than for people from those communities to break through: “People want the diverse voices, but they want white people to write those diverse voices. The staff aren’t diverse, so they will read the manuscript and the feedback you’ll get is, ‘I couldn’t relate to this, I don’t relate to these situations.’ And it’s like – well, no, you wouldn’t.”

Amy Mae Baxter was still a publishing trainee in 2019 when she founded Bad Form, an online magazine for writers of colour. “I didn’t know any who were being published, and I didn’t know anywhere I could go and find out about ones who were,” she explains. Now 25, she got into publishing herself via a Penguin Random House scheme for graduates from marginalised backgrounds; she now works for the Dialogue Books imprint led by one of the few senior black figures in publishing, Sharmaine Lovegrove. Three years on, Baxter reckons, most of the scheme beneficiaries have left publishing: “People come in at the bottom, they suffer, and then they leave, and that’s why the numbers aren’t changing. I’m white-passing Asian, and often I’m the darkest person in the room.”

This March was a “huge month” for Bad Form, thanks to a flurry of black-authored titles commissioned in response to the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests finally hitting the shelves. Her worry, however, is that they’re all now competing with each other, meaning some might not sell as well as they otherwise could have. The real test may come later this year when these writers seek second book deals.

Sites like Bad Form are part of a changing dynamic within publishing, whereby word-of-mouth buzz on Instagram, BookTok (a powerful influencer community on generation Z’s favourite social media channel, TikTok), and grassroots sites like Goodreads increasingly drive sales alongside established industry forces such as major bookstores and newspaper review sections. BookTok, says Baxter, “shifts books like you wouldn’t believe. A book like The Spanish Love Deception, by the Spanish writer Elena Armas – that’s been in the Sunday Times bestseller list for two weeks in a row, and it’s been out for over a year. It’s amazing, and all because a bunch of teenage girls liked it enough to make 10-second videos about it.”

By comparison, Twitter doesn’t sell many copies (one industry source says wryly that it’s full of “the sort of people who get sent books for free”). But it’s where writers, agents and editors come to research ideas, gossip, and argue in public. Despite the vitriol of its exchanges, Rajesh says the site was nonetheless one of the few places marginalised writers could be heard on the subject of Some Kids. After tweeting about it, she says, she was swamped with private messages from younger publishing staff saying, “Thank you for what the three of you did, because we’ve felt like this for a long time and we’re too frightened to speak up.” Crucially, some of them came from inside Picador.

Last December, Picador’s publishing director, Philip Gwyn Jones, told the Daily Telegraph he regretted not being braver in defending Clanchy, adding that younger staff seemed to believe they must agree with every book they issued. His words triggered such an internal backlash that he was forced to apologise, vowing to “use my privileged position as a white middle-class gatekeeper with more awareness”, while Picador’s insistence that his were not the imprint’s views sparked rumours of internal divisions. Few in the industry will now discuss this painful subject on the record.

The Clanchy fallout is not the only subject that is off the table in publishing circles. “There are certain authors or subjects people just won’t touch, because you know what the reaction will be on social media. People don’t want to be sworn at,” says a rival publisher. “I’ve heard mid-ranking people in publishing say, ‘I’d love to say something but I’ve got a mortgage to pay.’ It’s a really unhappy situation where everyone I know is having conversations behind closed doors.” The fear is not just of inadvertently publishing something problematic but of being accused of “micro-aggressions” against junior staff. “You might think we have a lot of power, but they have a lot of power on social media to destroy someone. Everyone’s saying half-jokingly: Am I going to get cancelled?”

What’s often portrayed as a generational divide, pitching “woke” young millennials against an ageing establishment, is in reality not so simple. Like the arts and academia, publishing is historically left-leaning and tends to attract the idealistic and value-driven at all ages. But it’s also dominated by recruits who can afford to do unpaid internships and move to London. The net result, this publisher argues, is an intake of privileged graduates anxious to compensate for their privilege, and growing resistance to publishing conservative voices they might disagree with. More than one industry source dates these tensions to Brexit and the rise of Donald Trump leaving many younger staff in particular keen not to fuel what they see as dangerous fires.

Last year, more than 200 employees at the US publisher Simon & Schuster signed a petition urging the firm not to publish a memoir by Trump’s vice-president, Mike Pence. Similar protests followed across the industry over books by the rightwing philosopher Jordan Peterson and “alt-right” activist Milo Yiannopoulos, while in Britain some staff at JK Rowling’s publisher, Hachette, were unhappy about working on her children’s picture book, The Ickabog, in light of Rowling’s views on trans rights.

The authors of the two big gender-critical feminist books published last year in Britain, Helen Joyce’s Trans: When Ideology Meets Reality and Kathleen Stock’s Material Girls, have both described battling to get published in Britain, and neither got US publishing deals. Caroline Hardman, the literary agent who originally approached Stock and suggested she write the book, stresses it is not uncommon for multiple editors to reject a title before one accepts it, but confirms that several editors passed on it. “Some people were saying, ‘Nobody will buy it; there’s no interest in this topic.’ But that wasn’t what I was seeing in my life – there was this groundswell of grassroots feminism and I had become aware of the Gender Recognition Act consultation [on making it easier to self-identify as trans]. I was thinking, ‘This is a really big thing,’’’ she says. “I did have some people who were interested, but knew they would get backlash internally.”

Eventually, Stock’s book became a bestseller for Oneworld. “Some editors have since written to me and said, ‘I wish I’d been braver,’” says Hardman. But while Stock and Joyce have proved there’s a market for gender-critical writing, Hardman isn’t sure it will be easier for others to follow: “You still get pushback, particularly in the US.”

The American publisher Skyhorse has established a reputation for publishing titles cancelled by its rivals, including Blake Bailey’s biography of the novelist Philip Roth (dropped following allegations of sexual harassment against Bailey, who denies any wrongdoing), and Woody Allen’s memoirs. Some have wondered whether Clanchy’s new publisher, Swift, envisages a similar anti-cancel culture model here. But when asked if this was the thinking behind republishing Some Kids, Richards says with feeling: “There are easier ways to make money.” He and his business partner simply felt that the book should be available and that nobody else would do it. “What I would say is we feel that publishing has a duty to stand by its authors, and in that particular case this hasn’t happened.” Picador, which has held its tongue since severing ties with Clanchy, did not want to comment for this piece. But the publisher’s unwillingness to defend a book whose every line it had previously cleared for publication still puzzles some of its rivals.

As founder of the feminist publishing house Virago, home of writers from Margaret Atwood to Maya Angelou, Carmen Callil is known for pushing the boundaries in publishing. She once resigned from the judging panel of the International Booker prize rather than see it go to Roth, “yet another North American”, at the expense of writers beyond the English-speaking world. Now 83 and retired from the industry, although still writing her own books, she is one of few senior figures prepared to reflect openly on Some Kids. She feels that both Clanchy and Pullman (whose publisher asked him to apologise for supporting Clanchy) were badly failed. “The first [duty] of a publisher is to their author. In neither case did the publisher go to the author and say, ‘It looks as if we’re in trouble here – what would you like me to do about it?’” she says. Callil resigned from the Society of Authors after concluding it had sided with Clanchy’s critics – something she blames on the author Joanne Harris, chair of its management committee, who declined to be interviewed for this piece.

While Callil does concede that “you can’t call children chocolate-coloured”, she feels Clanchy’s years of helping young people find their voices should count for something. “The point Philip Pullman was making is that these are terrible times for writers if they’re not going to be allowed to say things that are within the bounds of human understanding, that aren’t racist by massive intention.” Last month, Pullman resigned from the Society of Authors, saying he did not feel free to express his opinions in the post; the historian and writer Marina Warner also quit, warning of a “climate of anxiety” among authors. By email, Pullman says what most dismayed him was “the instant and unthinking cowardice on the part of publicists, organisations, institutions, corporations – the rush to abase themselves, and to try and make people like me abase ourselves, too, in the face of politically based criticism”.

The idea that writers who tackle difficult subjects cannot necessarily rely on their publishers’ backing in a storm clearly alarms some. One literary agent was approached recently by a white writer, asking if it was still acceptable to write a mixed-race character. “I said, ‘Yes, you’re a novelist – of course you can, but what you do have to prove is that you’ve done proper research, that you’re not just objectifying that character,’” she says. “That’s what fiction is for. It’s to do with looking through other people’s eyes.” But in nonfiction, she concedes, a more permanent shift may be under way. “Maybe we’ve too easily thought that we can tell anybody’s story without any deep understanding.”

One option for writers is enlisting a sensitivity or authenticity reader, who uses their own lived experience to advise on whether a text feels clumsy. To some, that’s censorship – Spectator columnist and novelist Lionel Shriver has said she’d rather quit writing – and to others it’s an unsatisfactory compromise, allowing famous white authors to expand their repertoires, rather than enabling more authentic voices to break through. But growing numbers agree with the author Juno Dawson, who used a sensitivity reader for a mixed-race character in her new novel, on the grounds that if she had accidentally caused offence, “I’d rather know while the book was a Word document and not on the shelves”.

Georgina Kamsika is a sensitivity reader for south Asian characters in everything from adult fiction to picture books. She checks for historical accuracy, authenticity and anything that instinctively makes her wince. “The general idea is to make sure that it will do no harm – there’s nothing in there that’s offensive or wrong or will give the wrong impression.” Growing up in Yorkshire as the child of Indian immigrant parents, Kamsika remembers “kids calling you things like ‘monkey-brain eater’” because of the way Indians were depicted in the film Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. But while children’s publishers have long exercised caution, aware that children take stories very literally, in adult publishing the use of sensitivity readers is infinitely more controversial.

Sign up to our Inside Saturday newsletter for an exclusive behind-the-scenes look at the making of the magazine’s biggest features, as well as a curated list of our weekly highlights.

Kamsika stresses that authors can always just ignore her recommendations. But the biggest misconception about sensitivity reading, she says, is that it promotes blandness. “It’s almost exactly the opposite. We want things to be rich, but just flavoured correctly. We want it just to taste like the correct recipe.” Often that means suggesting details writers can add to create livelier, more rounded characters. But she also recommends that authors ask themselves honestly whether they have the skills to tell a particular story. “Stories that are about pain, stories about being a person of colour, stories about slavery, stories about colonialism – those are stories that aren’t really easy for somebody else to write about.”

Since there is no officially recognised qualification for sensitivity readers, standards may well vary. Clanchy, who initially rewrote parts of Some Kids in response to the controversy, publicly ridiculed the three readers Picador commissioned last autumn to double-check this new version: one, she wrote scornfully, even suggested she capitalise the name of the poet e.e.cummings. The version she took to Swift was strictly her own work. Yet, on comparing it with the original, almost all the passages for which she was initially attacked have been rewritten. Gone are the chocolate skin and almond-shaped eyes, moustaches and “jarring” autistic traits; a pen portrait of an obese ex-pupil is noticeably softened. Yet the book’s spirit is – for better or worse – unchanged. If Picador had originally published something like this, could much grief have been avoided?

Making tea in the basement kitchen of her house in Oxford, Clanchy reaches for a mug emblazoned with a picture of her late mother, Joan, once a well-known headteacher. She has spent months clearing out her parents’ house, processing grief as she goes, and is feeling better than she did in December when she wrote for Prospect magazine that the shame of literary ostracism had made her want to die. But she still seems fragile, shrinking into the corner of an armchair, legs and arms protectively crossed. “My book is not a racist book, it’s an anti-racist book, and the ways that it was portrayed completely misportrayed the sense of the passages,” she says firmly, clutching the mug.

She has a new part-time teaching job, but would rather I didn’t say where, in case of recriminations; she still does creative writing work with asylum seekers, and is writing poems herself for the first time in years. Does she hope to be published again one day? “I expect I will write, in a way. I think I’m interesting; I think people are interested.”

Clanchy isn’t sure if she has actually been cancelled. “My books have been depublished, which is very unusual. I have lost my living. Everyone I know has suffered, all of my personal relationships have suffered. So I’ve suffered and I’m shamed and I’m unhappy a lot of the time – I don’t know if that’s cancelled enough? I’m not dead.” She has been called a white supremacist, accused of “Nazi-adjacent thinking”, and says that some “quite respectable people” mocked her bereavement online. “I think there is something about grieving that provokes rage – why should she have sympathy when we don’t have sympathy?’”

She still doesn’t know, she says, why Picador initially decided against defending the book; her editor, who was about to leave the imprint, wasn’t party to the decision to issue an apology. But it was her Prospect essay that triggered her final exit. Picador asked her not to write it, after the PR disaster of Gwyn Jones’s interview, but she didn’t see why she shouldn’t; after that, she says, both sides concluded it was over. Yet it sounds as if the relationship really began breaking down last summer, when Picador apologised without (she says) consulting her, a decision she thinks merely encouraged her critics. “In not standing by the text they said, ‘You can say anything bad about this text, as bad as you like. It’s a free-for-all. You can destroy this person’s professional life.’”

She removed the contested phrases from the new version of Some Kids because they couldn’t be read without resurrecting the row, she says, not because she necessarily agrees they’re offensive. The girl whose “almond eyes” she wrote about, from the persecuted Hazara ethnic group in Afghanistan, has since said publicly that she liked the description and sees it as part of her identity; Clanchy is adamant that Hazaras see their looks as part of the basis of their oppression. “It’s a politicised, important phrase and to take it out and say it was a piece of colonialism is a ludicrous and false caricature.” Similarly, she wrote about one boy’s chocolate skin, she says, “because that’s what that young person constantly used in their own work”. It was, she adds, “as a kind of hidden tribute to that person. I didn’t mean to upset anybody but I’m quite happy to remove that if it upset people.”

But she’s audibly exasperated with the sensitivity readers’ response to what she regards as essentially factual statements, like her blunt assessment that children with foetal alcohol spectrum disorder (brain damage caused by mothers drinking in pregnancy) don’t progress at school. “If we’re going to object and say that because something is sad we mustn’t say it – that’s a fundamentally worrying thing about publishing.”

If she’d had sensitivity readers from the start, though, couldn’t they have caught some of the wording that upset people and caused her such grief? She’s unconvinced; there would always, she thinks, have been something. When I ask if given the time again she would still write Some Kids, she says: “I think the controversy really took on a life of its own and hurt everybody, and I wish that hadn’t happened, but I don’t un-wish my book. I don’t think I shouldn’t have written it.” Her greatest regret, apart from no longer being invited to teach other teachers, is that ex-pupils who publicly defended her have been “patronised and disbelieved”.

Clanchy does concede that she “overreacted” to the initial Goodreads criticism, while insisting she genuinely didn’t use some phrases falsely attributed to her, like “slanty-eyed” and “Jewish nose” (although she did write “Ashkenazi nose”). She remains bewildered by what befell what she thinks of as a “gentle, liberal” book. “I truly don’t understand, although obviously I worry and wonder about it a lot.”

In other creative industries, so-called cancel culture has proved a surprisingly elastic phenomenon, with high-profile figures bouncing back from what looked like professional oblivion, and a vigorous pro-free speech movement emerging. The comedian Dave Chappelle returned to Netflix last year within months of being supposedly “cancelled” for jokes deemed transphobic. Elon Musk’s promised takeover of Twitter may also change the role it plays, with conservatives expecting the billionaire and free-speech absolutist to end what they see as suppression of their views on social media. At least one veteran agent predicts that publishing, too, will eventually find a new equilibrium: “I feel like the pendulum will swing – not back to where it was; I don’t want it where it was. It is a necessary corrective. But like all pendulum swings, it’s gone to a sort of crazy place. We’ll come back to a new normal, and there will be important discoveries of new writers in that.” Yet few see a route back into mainstream publishing for Clanchy, for reasons perhaps more complex than they look.

Liberal as it undoubtedly is, there’s something distinctly confrontational about Some Kids, thanks partly to Clanchy’s compulsive candour about things more self-protective writers might withhold; her feelings on escorting an 18-year-old ex-pupil to a gay club, or comparing her pupils’ instant scoffing of the biscuits distributed in class with what she regards as her own middle-class ability to resist instant gratification and stay slim. It’s faintly reminiscent of Adam Kay’s medical memoir This Is Going to Hurt, another Picador title recently adapted for television, in which some perceived misogynistic overtones.

Kay’s labour-ward tales of gory deliveries and prolapsed vaginas also described things he had witnessed but as a man cannot personally experience; he, too, wrote sometimes brusquely about people he saw at their most vulnerable. The positive birth campaigner Milli Hill has said that it’s telling how many people found all this hilarious, right up until women who had endured traumatic births objected. Yet Callil, a lifelong scourge of misogyny, tells me she loved Kay’s book. Is one woman right and the other wrong? Or are these judgment calls – whether made by editors, sensitivity readers, critics or book buyers – sometimes more subjective than we’re comfortable acknowledging?

In both books there’s a jangling disconnect between a sometimes abrasive narrator’s voice and their nurturing professions, which throws the reader off balance. Kay has said TV producers praised his bravery in “making your character so actively dislikable”. Yet the occasional callousness many readers found hurtful can be an indicator of professional burnout in medicine, and Kay did ultimately quit. Had he smoothed that out, perhaps a dimension of the story would have been lost. Would the same be true if Clanchy had written something less spiky?

As it is, both books reveal perhaps more than their authors consciously intended; that doctors aren’t always caring; that teachers can be judgmental in private; that good people can think harsh thoughts. It may even be the exposure of such unpalatable truths that turns “writing into art”, as the Orwell prize criteria put it. But only, perhaps, where those truths are worth the pain.