Enrollment in American higher education just declined. Again.

![]() That means the total number of students taking classes in American colleges and universities during spring 2022 went down compared to the previous semester (fall 2021) and the prior spring term (2021). The numbers and analysis just appeared from the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

That means the total number of students taking classes in American colleges and universities during spring 2022 went down compared to the previous semester (fall 2021) and the prior spring term (2021). The numbers and analysis just appeared from the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

In this post I’ll unpack what the data show, then offer some reflections based on my work as a higher education futurist. I hope I can add to the discussion thus far.

A couple of caveats before proceeding: first, this is macro, sector-level data. It’s about the entirety of United States post-secondary education. Obviously there will be variations of all kinds between regions, states, localities, and individual campuses. Second, this is the first published data on spring 2022. The Clearinghouse usually follows up their initial releases with followups based on additional research. So consider this data provisional for now.

The Clearinghouse report

At the big picture level, “[t]otal postsecondary enrollment, which includes both undergraduate and graduate students, fell a further 4.1 percent or [by] 685,000 students in spring 2022 compared to spring 2021.” [emphasis added] The total number of students stands at 15,917,249. Comparing this semester to the one just before, “The declines this spring are also markedly steeper than they were last fall, when total postsecondary enrollment declined by 2.7 percent from the previous fall.”

How does this decline play out within different levels of higher education? Everyone got hit: “Enrollment declined this spring at both undergraduate and graduate levels.” However, “[u]ndergraduate enrollment accounted for most of the decline, dropping 4.7 percent this spring or over 662,000 students from spring 2021.” Comparing 2022 to fall 2021, “[u]ndergraduate enrollment is also falling more steeply this spring than it was in fall 2021 (-4.7% vs. -3.1%).”

How did different types of institutions fare? Numbers were not good across the board, as each group lost students:

If we look at campuses by public versus private funding (in the US, “public” means nominally state-funded), the former were hit hardest. “Public institutions suffered the brunt of enrollment declines this spring, losing 604,000 students (-5.0% from a year ago).”

If we break things down by institutional identity, “[c]ommunity colleges accounted for more than half of these losses this spring (351,000 students).” Worse for that large and underresourced sector, “[f]or a second straight year, community colleges suffered double-digit declines in full-time students, amounting to nearly 11 percent (168,000 students) this year and 20.9 percent (372,000 students) for the two years since spring 2020.” Note, too, that “[a]t private non-profit four-year institutions, part-time student enrollment dropped this spring (-4.1%), reversing last year’s gains (+2.8%).”

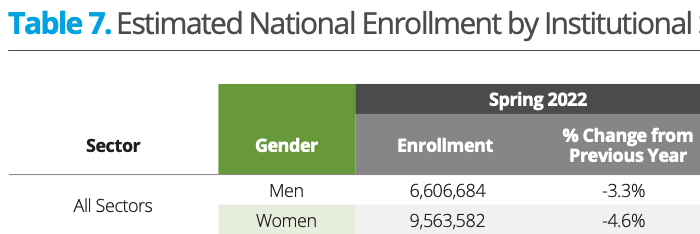

What demographic results does the Clearinghouse offer? They sliced their data by gender, which shows two things. Women continue to significantly outnumber men, further establishing a twenty-first century reversal of prior centuries. Meanwhile, both genders saw enrollment declines:

The report didn’t break down the full picture by race. They did analyze the first-year student population this way, however, and the results are mixed:

By race and ethnicity, Asian and Latinx freshmen numbers grew nationally in spring 2022 (+15% and +4%, 1,700 and 2,300 students, respectively). In contrast, Black freshmen declined by 6.5 percent (2,600 students), compounding previous losses for a total of 18.7 percent (8,400) fewer Black freshmen than in spring 2020.

How does the enrollment picture play out by states? Things varied. The states losing the largest number include Arkansas (7.1%), Missouri (7.1%), Washington (7.2%), Vermont (7.2%), California (-8.1%), and Michigan (15.5%). Gainers number New Hampshire (8.2%), Colorado (9.0%), and Indiana (10.7%).

(The Clearinghouse cautions that for some of these states, “a large institution had inconsistent data submission across years, making enrollment estimates less accurate. Interpret the data with caution…” They include Colorado, Michigan. A similar caution applies to Indiana, whose “[d]ata for 2022 were impacted by reclassification of for-profit four-year institutions.”)

What does this data say about the impact of COVID? It looks like the enrollment drop we suffered during the pandemic’s height continues, even as deaths have plummeted and the country seems to have moved on.

Following a 3.5 percent drop last spring, postsecondary institutions have lost nearly 1.3 million students since spring 2020… As a result, the undergraduate student body is now 9.4 percent or nearly 1.4 million students smaller than before the pandemic.

Community colleges have suffered the worst, “hav[ing] lost over 827,000 students since the start of the pandemic.”

Let me offer another view with some COVID-era numbers from the report, for total enrollment:

Spring 2020 – 17,185,751

Spring 2021 – 16,586,893

Spring 2022 – 15,917,249

Were there any bright spots in the report? Perhaps. There is one glimmer of potential light having to do with first-year students:

A special analysis of the spring freshmen highlights distinctive pandemic-related enrollment trends. Nearly 340,000 students started college for the first time this spring, an increase of 4.2 percent from spring 2021. However, the growth this spring was not enough to return community college freshman enrollment to pre-pandemic levels, with the current freshmen numbers still running 7.9 percent (17,000 students) below spring 2020’s levels.

Further, primarily online institutions continued to do well. “[S]everal states experienced growth because students enrolling in primarily online institutions based in these states have been increasing…” Not everyone will see this as positive, however. Some deem online learning inferior to in-person, while others criticize some of the institutions involved.

Some reflections

I’ve been tracking this enrollment trend for more than a decade. Every year since 2011-2012, every semester student numbers have ticked down. COVID accelerated the trend, making the decline more pronounced.

Personally, I am struggling mightily to avoid hollering “I told you so!” Far too many times I’ve been the only person in a room or event pointing this out, and warning people about the futures it might entail. Also, for twenty years (!) before that (!) I’ve been telling academics to get online and helping them do so. My track record on this gives me a basis to crow from. But it also gives me little pleasure, because the academic realities represent so much loss and suffering. I will hold myself back.

So what might this trend’s continuation mean for higher education’s future?

Financials The overwhelming supermajority of American colleges and universities depend on students for their financial stability, as only a handful are rich enough to draw on fat endowments, and most public universities receive a minority of their funding from their state governments. Students, in contrast, bring in the bulk of dollars through the tuition, fees, room, and board they or their families or external supporters provide. Losing students strikes at the heart of college and university sustainability.

Politically, this makes it harder for public universities to ask their state governments for more money. “We’re teaching fewer students, and therefore deserve a funding increase” is not the most appealing argument. Remember that states have massively cut those dollars already, and the politics aren’t great for getting more.

Within academia, a shrinking enrollment scenario may deepen our competitive instincts. This can make collaboration harder to support. It can also empower administrations to cut. Plunging enrollment is almost universally cited in queen sacrifices.

Online Note that primarily online institutions did well, once again. Southern New Hampshire, Western Governors, et al seem to be moving from strength to strength – although Liberty University might not, hobbled by scandals. Will the overall trend encourage more colleges and universities to seek more students online, and/or shrink their in-person footprint? The “end” of COVID suggests a joyous return to in-person learning, but we’re not seeing that borne out in the sector as a whole.

For-profit resurgence? I am curious about for-profits. Their massive enrollment losses seem to be tapering off. Are they about to return to their early twenty-first century growth habits? Buried in the data is a sign of their growth:

Did you catch that? Of all American higher ed sectors, the only one enjoying enrollment growth among people 24 and younger are the for-profits. Their excellent marketing capacity must be doing well. Will the Biden administration follow the Obama in cracking down on this sector? Or will we see another for-profit resurgence?

Community colleges They doesn’t get much discussion or media buzz, but this large swath of American higher ed is all about access. They have been suffering since the Great Recession.

Not paying much attention These numbers are actually easy to ignore. They describe an entire sector, and American academics – Americans in general – don’t usually think in these terms. We prefer to think about a given campus, or a certain discipline/profession, or sometimes of a subsector, like the liberal arts college world. After all, it’s a vast country. Those in states not suffering a Michigan-level plummet can count themselves fortunate. Those working in institutions whose enrollments are stable or even growing can cling to that data. In other words, a lot of folks who focus on things other than the trend this report bears out.

The mission of more college Starting in the 1960s, American culture began to seriously consider the idea that the nation would be better off with a lot more people going to college. By the 1980s this had become a country-wide consensus, and so a long boom took off. Yet since 2012 enrollments have dipped and dipped.

Looked at one way, if American higher ed is committed to increasing access to the post-secondary educational experience, we’ve been failing for a decade. Looked at another way, that national consensus may be breaking up right now. How else to describe so many people voting with their feet and avoiding campuses?

Perhaps we’ll regain that consensus, somehow. At some point either WHO or CDC will declare COVID-19 to be endemic, rather than pandemic, and the people who believe either may joyously send their family members to classes again. The powerful demand for more STEM degrees could elicit students taking those paths for presumably well paying futures. Maybe more campuses will choose to teach adults and elders, as our population ages. My call for higher ed to prepare the world for the climate crisis might find students who agree. Perhaps America will repair its global reputation for hating immigrants and loving to shoot each other, eliciting a new flood of international students. Perhaps a younger generation, lacking Cold War cultural programming about the evils of socialism, will consider collective good a viable thing. Perhaps.

As a futurist, I try to envision multiple and contradictory futures, so I make room for that one. We could rerun the 1980s and enjoy a new boom. But I also fear the opposite, because lots of forces push hard on keeping enrollment further down. The specter of student debt looms large and isn’t going away. If the Biden administration somehow staggers forward with some forgiveness package, all of the structures which inflated the hideous debt balloon are still operating, so we’ll reach $1.7 trillion again and beyond. Conservative criticism of education continues to thrive. The skilled trades beckon, as their workers age up. The consensus could wither away and we return to a cultural sense like we saw in the 1950s: college being a nice thing to have, especially for the deserving. Or the consensus will splinter along culture war lines, and universities become even more of a blue zone, hated by the red.

Sliding down the peak Way back in 2013, when enrollments started to dip down after a generation+ of growth, I first raised the idea of peak higher education. That scenario meant higher ed numbers would keep declining, and decline they have, every single year since. In the fall of 2011 American higher ed enrolled 20,556,272 students. Now we just taught 15,917,249. That’s 77.4% of where we were, a drop of 22.6%.

With this week’s Clearinghouse research, we continue to fit that peak higher education scenario all too well.