2025-2050

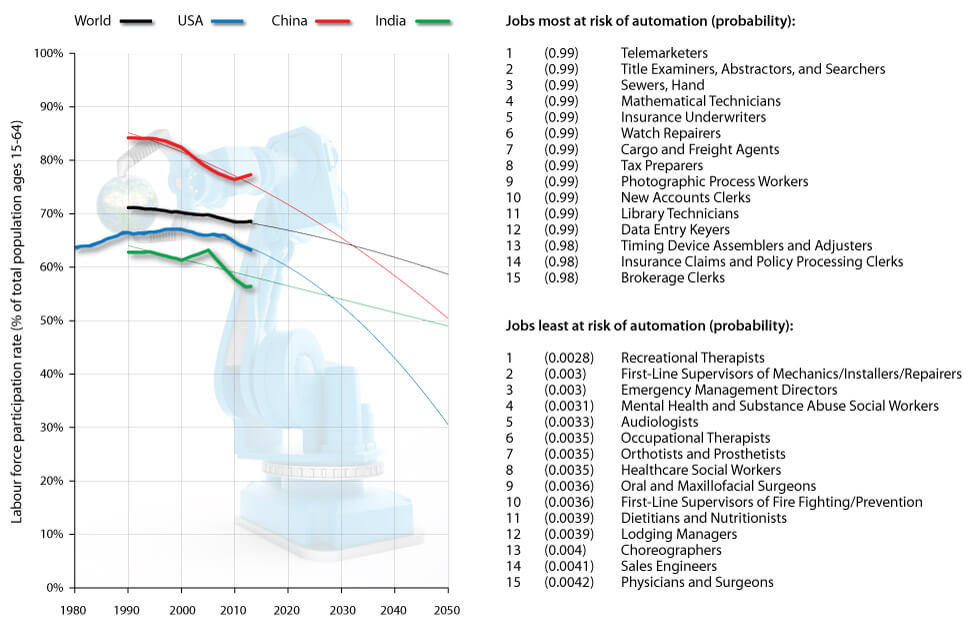

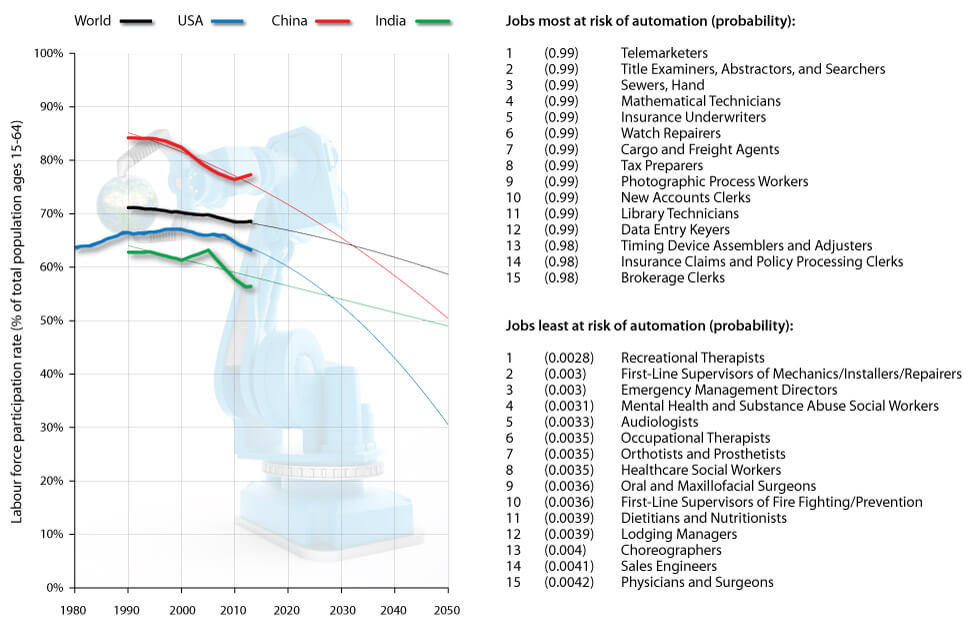

Technological unemployment is rising rapidly

The second quarter of the 21st century is marked by a rapid rise in technological unemployment around much of the world.* This results in considerable economic, political and cultural upheaval. For most of the 200 years since the Industrial Revolution, new advances in technology and automation had tended to create more jobs than they destroyed. By the 21st century, however, this was no longer true. A fundamental change had begun to occur.**

Median wages, already falling in recent decades, had continued to stagnate – particularly in the West.*** Globalisation and the outsourcing of jobs to overseas markets with lower international labour rates had, of course, been partly responsible in the past. But a growing and rapidly accelerating trend was the impact of machines and intelligent software programs. Not only were their physical abilities becoming more humanlike;******** in many ways their analytical and cognitive skills were beginning to match those of people too.******

Blue collar workers had traditionally borne the brunt of layoffs from technological unemployment. This time, white collar jobs were no longer safe either.* Advanced robotics, increasingly sophisticated algorithms, deep learning networks, exponential growth in computer processing power and bandwidth, voice/facial recognition and other tech – all were paving the way towards a highly automated society. Furthermore, of the (few) new jobs being created, most were in highly skilled roles, making it hard or impossible for those made redundant to adapt. Many workers now faced permanent unemployment.

By 2025, transport was among the sectors feeling the biggest impacts.* The idea of self-driving vehicles had once been science fiction, but money was being poured into research and development. In 2015, the first licenced autonomous truck was announced. These hi-tech vehicles saw rapid adoption. Initially they required a driver to be present, who could take over in case of emergencies, but later versions were fully autonomous.* In the US alone, there were 3.5 million truck drivers, with a further 5.2 million people in non-driving jobs that were dependent on the truck-driving industry, such as highway cafes and motels where drivers would stop to eat, drink, rest and sleep. A similar trend would follow with other vehicle types,* such as taxis, alongside public transport including trains – notably the London Underground.* With humans totalling 1/3rd of operating costs from their salaries alone, the business case was strong. Self-driving vehicles would never require a salary, training, sleep, pension payments, health insurance, holidays or other associated costs/time, would never drink alcohol, and never be distracted by mobile phones or tempted by road rage.

Manufacturing was another area seeing rapid change. This sector had already witnessed heavy automation in earlier decades, in the form of robots capable of constructing cars. In general, however, these machines were limited to a fixed set of pre-defined movements – repetitive actions performed over and over again. Robots with far more adaptability and dynamism would emerge during the early 21st century. Just one example was “Baxter”, developed by Rethink Robotics.* Baxter could understand its environment and was safe enough to work shoulder-to-shoulder with people while offering a broad range of skills. Priced at only $22,000 this model was aimed at midsize and small manufacturers, companies that had never been able to afford robots before. It was fast and easy to configure, going from delivery to the factory floor in under an hour, unlike traditional robots that required manufacturers to develop custom software and make additional capital investments.

Robots were increasingly used in aerospace,* agriculture,*** cleaning,* delivery services (via drone),** elderly care homes, hospitals,* hotels,** kitchens,** military operations,**** mining,* retail environments,* security patrols** and warehouses.* In the scientific arena, some machines were now performing the equivalent of 12 years’ worth of human research in a week.* Rapid growth in solar PV installations led some analysts to believe that a new era of green jobs was about to explode,* but robots were capable of this task with greater speed and efficiency than human engineers.*

Holographic representations of people were also being deployed in various public assistant/receptionist roles. While the first generation lacked the ability to hold a two-way conversation, later versions became more interactive and intelligent.**

Other examples of automation included self-service checkouts,* later followed by more advanced checkout-free payments via a combination of sensors and machine vision* (which also enabled stock levels to be monitored and audited without humans). Cafes and restaurants had begun using a system of touchscreen displays, tablets and mobile apps to improve the speed and accuracy of the order process,* with many establishments also providing machines to rapidly create and dispense meals/drinks,* particularly in fast food chains like McDonalds.

AI software, algorithms and mobile apps had exploded in use during the 2010s and this trend continued in subsequent decades. Some bots were now capable of writing and publishing their own articles online.* Virtual lawyers were being developed to predict the likely outcome and impact of law suits; there were virtual doctors and medical bots (such as Watson), with increasingly computerised analysis and reporting of big data (able to find the proverbial “needle in a haystack” with hyper-accuracy and speed);* virtual teachers and other virtual professions.

3D printing was another emerging trend, and by the mid-2020s had more than tripled in market size compared to 2018.* It found mainstream consumer uses in the home and was increasingly used in large-scale formats and industrial settings; even for vehicle and building constructions. By 2040, traditional manufacturing jobs had been largely eliminated in the US* and many other Western societies. Meanwhile, the ability to quickly and cheaply print shoes, clothing and other personal items was impacting large numbers of jobs in developing nations, particularly those in Asian sweatshops.*

The tide of change was undeniable. All of these developments led to a growing unemployment crisis; not immediately and not everywhere, but enough to become a major issue for society. Unions in the past had attempted to protect their workers from such impacts, but memberships were at record lows – and in any case, they had never been particularly effective in slowing the march of technology and economics.

Sources: World Bank* and the Oxford Martin Programme on the Impacts of Future Technology*

Governments were now facing profound questions about the nature and future direction of their economies. If more and more people were being made permanently unemployed, how could they afford to buy goods and services needed to stimulate growth? Where would tax revenues come from? Confronted by increasingly angry and desperate voters, now protesting on scales dwarfing Occupy Wall Street, many leaders between 2025 and 2050 began formulating a welfare system to handle these extraordinary circumstances. This had gone by several names in the past – such as basic income, basic income guarantee, universal basic income, universal demogrant and citizen’s income – but was most commonly referred to as the unconditional basic income (UBI).

The concept of UBI was not new. A minimum income for the poor had been discussed as far back as the early 16th century; unconditional grants were proposed in the 18th century; the two were combined for the first time in the 19th century to form the idea of unconditional basic income.* This theory received further attention during the 20th century. The economist Milton Friedman in 1962 advocated a guaranteed income via a “negative income tax”. Martin Luther King Jr. in his final book, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?, wrote: “I am now convinced that the simplest approach will prove to be the most effective – the solution to poverty is to abolish it directly by a now widely discussed measure: guaranteed income.” US President Richard Nixon supported the idea and tried (unsuccessfully) to pass a version of Friedman’s plan. His opponent in the 1972 election, George McGovern, also suggested a guaranteed annual income.

Traditional welfare payments, such as housing benefit and jobseeker’s allowance, were heavily means-tested. In general, they provided only the bare minimum for survival and well-being of a household. By contrast, UBI would be more generous. Unconditional and automatic, it could be paid to each and every individual, regardless of other income sources and with no requirement for a person to work or even be looking for work. The amount paid would make a citizen “economically active”, rather than idle, in turn stimulating growth. Some would use the UBI to return to education and improve their skills. Those with jobs would continue to earn more than those who did not work.

In most countries, UBI would be funded, in part, by increased taxation on the very rich.* At first glance, this appeared to be a radical left-wing concept involving massive wealth redistribution. For this reason, opposition was initially strong, particularly in the US. As time went by, however, the arguments in favour began to make sense to both sides of the political spectrum. For example, UBI could also be funded by cutting dozens of entitlement programs and replacing them with a single unified solution, reducing the size of government and giving citizens more freedom over their personal finances. Demographics in the US were also shifting in ways that made it very difficult for Republicans to maintain their traditional viewpoints.* With pressure mounting from mass social protests – and few other plausible alternatives to stimulate consumer spending – bipartisan support was gradually achieved. Nevertheless, its adoption in the United States (as with universal healthcare) occurred later than most other countries. Switzerland, for example, conducted a popular referendum on UBI as early as 2016,* with a proposed amount of $2,800/month. Meanwhile, a small-scale pilot project in Namibia during 2004 cut poverty from 76% to 37%, boosted education and health, increased non-subsidised incomes, and cut crime.* An experiment involving 6,000 people in India had similar success.*

In the short to medium term, rising unemployment was highly disruptive and triggered an unprecedented crisis.* For the US, in particular, it led to some of the biggest economic reforms in modern history.* In the longer term, however, it was arguably a positive development for humanity.* UBI acted as a temporary bridge or stepping stone to a post-scarcity world, with even greater advances in robotics and automation occurring in the late 21st century and beyond.**

2025-2035

All television is becoming Internet-based

During this period, cable TV and other traditional modes of television are beginning to disappear in favour of Internet-based streaming. The inflexibility of scheduled programmes had made them increasingly unattractive, with users shifting instead towards on-demand services providing greater choice, convenience and value for money. By the late 2010s, more people were streaming video online each day than watching scheduled linear TV.* This trend continued into the following two decades,* resulting in a huge loss of subscribers for older traditional media companies,* which were forced to either evolve or die.

In Britain, the traditional TV licence fee (£157 annually, as of 2020) had been called into question, with many believing it should no longer be mandatory for all television owners. A Royal Charter guaranteed the licence fee funding until 2026, but the Conservative government proposed alternative methods of financing the BBC in the future.* Among the moves suggested for implementing a new system were the use of advertising revenue, a new broadcasting levy and the switch to a subscription-based system. This had been expected to reduce the power and influence of the BBC. However, the next Royal Charter extended the licence fee’s use from 2026 until 2038.*

The visual quality of TV sets, tablets and other devices has markedly improved compared to previous generations, with 8K and even higher resolutions now cheap and ubiquitous. Connection speeds are improving in parallel, with 5G and its successor generating exponential growth in web data. By the early 2030s, it is fairly common for users in developed nations to have 6G and a terabit web connection.

Furthermore, access and coverage has been made easier via expanded rural and remote networks, greater use of public Wi-Fi spots, high-altitude balloons and growth of satellite constellations. With nearly all of the world now coming online, the resulting flow of knowledge contributes to public demonstrations and greater awareness of political issues, corruption and injustice. Citizen journalists can record and disseminate their experiences on video – using mobile apps to capture footage of war crimes and human rights abuses, for example.*

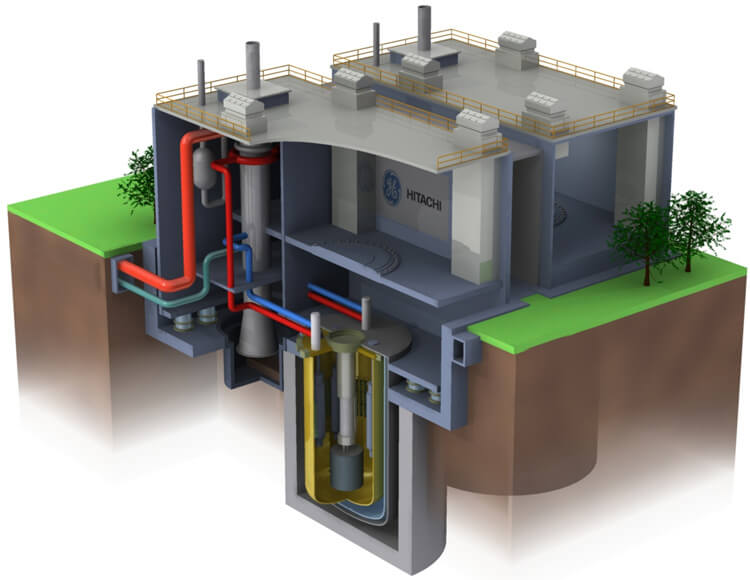

Small modular nuclear reactors gain widespread adoption

Small modular reactors (SMRs) are a new class of smaller, cheaper, safer and more adaptable nuclear power plants that gain widespread adoption from the mid-2020s to the mid-2030s.* They are defined by the International Atomic Energy Agency as generating an electric output of less than 300 MW, reaching as low as 10 MW for some of the smallest versions. This is compared to larger, conventional reactors, which typically produce 1 to 2 GW.

Electricity was first generated from nuclear energy in 1951, during tests of an experimental reactor in the high desert of Idaho. The original output was estimated at 45 kW. In subsequent decades, reactors grew much larger, with outputs reaching the gigawatt scale. Later, more than half a century after the first commercial use of nuclear energy, reactor designs with lower electrical outputs were starting to be developed again.

In the early decades of the 21st century, the need for small modular reactors was arising due to several different factors. Firstly, they could be built at a much lower cost than traditional reactors, making them less risky from an investment viewpoint. They were especially attractive to developing nations (which lacked the ability to spend tens of billions of dollars on infrastructure), to remote communities without long distance transmission lines, and for areas with limited water and/or space.

SMRs could be designed with flexibility in mind. Unlike the larger power plants (most of which used “light water” designs based on uranium fuel and ordinary water for cooling), they were being developed in a broad range of shapes and sizes, with various fuels and cooling systems. Some could even use existing legacy radioactive waste as an energy source. Among the most promising concepts were those able to be assembled in factories and delivered in sealed containers – meaning the plant would never require decommissioning, but could simply have its power source replaced like a battery, further reducing costs. In a similar vein, some of the other proposed concepts generated far less waste than conventional reactors. SMRs would also allow increments of capacity to be gradually added as power needs increased over time.

There were yet more advantages. The smaller size and safety features of the SMRs would mean both a reduced environmental impact and little or no damage from an accident – easing public concerns – while ensuring a faster and simpler planning process. Being much smaller and easier to construct, the time required from ground breaking to commercial operation could be greatly reduced, compared to larger power plants that often required decades to plan, build and test. Additionally, the threat of nuclear weapons proliferation was eliminated by the design, materials and safety aspects of SMRs.

This variety and flexibility, alongside the demand for lower carbon energy, was leading to a renaissance in nuclear power generation. By the mid-2010s, around 50 experimental prototype SMRs were in development (excluding nuclear submarines and ships). A small number achieved commercial viability in the early 2020s** and these paved the way to greater adoption through the following decade.* By 2035, the SMR industry is generating several tens of gigawatts in energy and is valued at nearly half a trillion dollars worldwide.*

The Advanced Technology Large-Aperture Space Telescope (ATLAST) conducts its life-searching mission

The Advanced Technology Large-Aperture Space Telescope (ATLAST) is a major new space observatory launched by NASA. It has substantially higher resolution than Hubble and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), with a primary mirror that dwarfs both. Its angular resolution is 10 times better than JWST, with a sensitivity limit up to 2,000 times better than Hubble.

ATLAST is a flagship mission of the 2025-2035 period, designed to address one of the most compelling questions of our time: is there life elsewhere in the Galaxy? It attempts to accomplish this by detecting “biosignatures” (such as molecular oxygen, ozone, water and methane) in the spectra of terrestrial exoplanets.*

Operating in the ultraviolet, optical and infrared wavelengths, its mirror is so powerful that it can distinguish the atmosphere and surface of Earth-sized exoplanets, at distances up to 150 light years – including their climate and rotation rate.* ATLAST enables astronomers to glean information on the nature of dominant land features, along with changes in cloud cover. It even has the potential to detect seasonal variations in surface vegetation.

In addition to searching for life, ATLAST has the performance required to reveal the underlying physics driving star formation and to trace complex interactions between dark matter, galaxies and the intergalactic medium.

The observatory is placed at Sun-Earth Lagrange point L2. Servicing and maintenance are performed using a robotic ferry, with occasional help from astronaut crews flying in the Orion spacecraft (which allows NASA to gain experience for manned Solar System missions). Like the Hubble Space Telescope, ATLAST has a 20-year lifespan. By the 2050s, it is being succeeded by telescopes of truly prodigious magnitude, offering detailed close-up views of distant exoplanets.*

Mouse revival from cryopreservation

Cryopreservation – a process where cells or whole tissues are preserved by cooling to sub-zero temperatures – witnesses major advances during this period. By far the most notable achievement is a mouse being revived from storage at −196°C.

In the past, among the most serious challenges to overcome had been damage from crystallisation as a result of the freezing process. During the first decade of the 21st century, this problem was comprehensively solved by the development of cryoprotectants offering complete vitrification. In other words, the body being preserved was turned into a glass, rather than crystalline solid.

A number of issues remained, however – such as the toxicity of these cryoprotectants, as well as the fracturing that occurred due to simple thermal stress. In subsequent decades, research saw a dramatic acceleration and resulted in progressively more successful techniques, culminating in the mouse revival.*

Although a human revival is still many years away (and fraught with ethical, legal and social hurdles), such a feat now appears to be a realistic prospect. Once considered the stuff of science fiction, cryopreservation becomes an increasingly regular feature in mainstream scientific literature. Many new startup companies are formed around this time, promising to “resurrect” people at some future date.

Photo courtesy of Alcor Life Extension Foundation.

2025-2030

Many cities are banning fossil fuel-powered vehicles

During this period, many cities and regions around the world enforce outright bans on the use of traditional petrol and diesel-powered vehicles. This is primarily to meet climate targets under international agreements such as the Kyoto Accord and the Paris Agreement, but is also for reasons of energy independence and improved air quality.

Among the first places to announce bans were Athens, Madrid, Paris and Mexico City. In December 2016, the mayors of each city pledged to take diesel cars and vans off their roads by 2025. Over the next few years, many more plans were announced for partial (diesel only) or complete bans (both gasoline and diesel) in more than 20 countries. The vast majority would cover the 2025-2030 timeframe, with some being implemented sooner (e.g. 2020 for Oxford, UK) and a few others later (e.g. 2040 for China, France and the UK). For these ‘outliers’ in 2040, it was subsequently suggested that these timelines were not ambitious enough and should be brought forward.

By the early 2020s, a flood of additional countries had joined this planned phase out. With zero-emission vehicles now cheaper than ever, their numbers were growing exponentially, regardless of any bans or regulations. Batteries had been the main reason why electric cars were more expensive than their internal combustion engine (ICE) counterparts, but these prices have declined at such a rate that the overall price balance has flipped by the late 2020s.* The relative cost difference continues to widen each year – making them the preferred option from now on. Progress also continues to be made with fuel cell and other clean technology vehicles. Many cities around the world are now finally beginning to see a noticeable improvement in their air quality.*

The

threat of bioterrorism is increasing

Biotechnology

is now sufficiently advanced, widespread and inexpensive that a small

group of people – or even a single person – can threaten the survival

of humanity. Desktop fabrication labs, genetic databases and AI software

are becoming accessible to the public. These enable the rapid research

and synthesis of DNA, for those with appropriate technical knowledge.

Criminals

have already begun to exploit this – providing access to drugs and other

substances without prescriptions, for example (like offshore Internet

pharmacies of earlier decades) – and now terrorists are making use of

them too.

In the

past, government agencies were able to combat bioterrorism by restricting

access to pathogens themselves. This was achieved by regulating the

laboratory use of potentially deadly agents, such as the Ebola virus.

However, the advent of DNA synthesis technology means that simply restricting

access to the actual pathogen no longer provides the security it once

did. Since the gene sequence is a “blueprint”, i.e. a form

of coded information, once an organism has been sequenced it can be

synthesised without using culture samples or stock DNA.

As synthesis

technology has continued to advance, it has become cheap, more accessible

and far easier to utilise. Like the personal computer revolution of

the early 1980s, biotechnology is diffusing into mainsteam society.

At the same time, the ongoing need for medical breakthroughs has necessitated

a gradual easing of database regulations. Furthermore, the DNA sequences

for certain pathogens – such as anthrax, botulism and smallpox – have

already been available on the Internet, for decades.

It has therefore

become alarmingly easy to produce a new virus (possibly an even deadlier

version of an existing one) using a relatively low level of knowledge

and equipment. One such

home-made bioweapon is unleashed around this time,* with significant worldwide impacts.

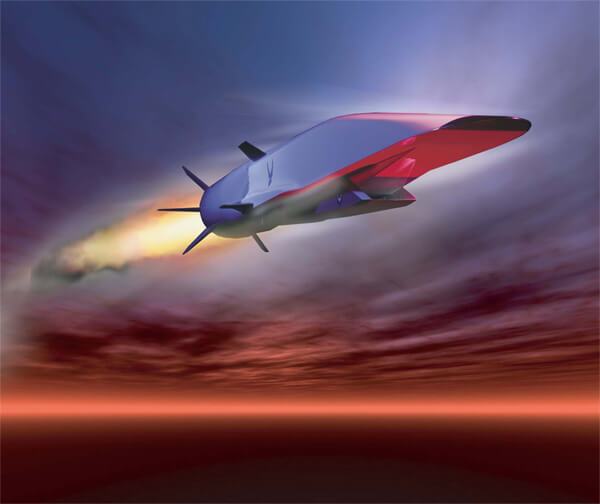

Hypersonic missiles are in military use

When launched, cruise missiles have typically reached 500-600 mph (800-965 km/h). However, a new generation of air-breathing supersonic combustion ramjet (scramjet) engines is now emerging after many years of testing and development. These are capable of exceeding Mach 5, or about 3,840 mph (6,150 km/h), making them hypersonic.*

As well as enhancing the responsiveness of a warfighter, the survivability of these missiles as they fly over enemy territory is greatly improved, since they are difficult (if not impossible) to hit at such a high speed.

Now that military use of scramjets has been perfected, commercial use will soon follow. In the 2030s, the first hypersonic airliners begin to appear, capable of travelling around the globe in under four hours.**

Some of Britain’s most well-known animal species are going extinct

Due to a combination of habitat loss, agricultural intensification, road accidents, pesticides, pollution and other human interference, some of Britain’s most iconic and well-known animals are disappearing. This includes hedgehogs, red squirrels, cuckoos, brown hares, Scottish wildcats, natterjack toads, red-necked phalaropes, woodland grouse, and turtle doves.*** Many butterfly species have also declined drastically.*

2025-2029

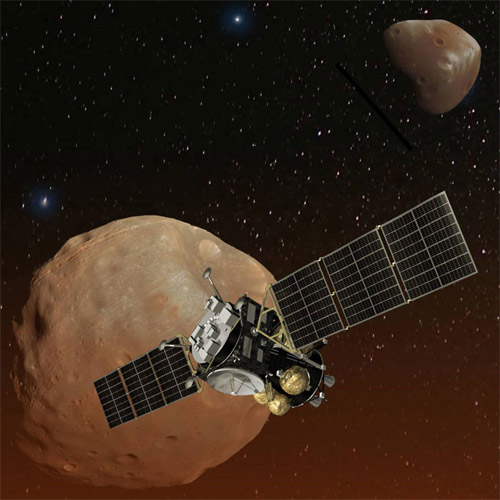

The Martian Moons Exploration probe collects and returns samples

Martian Moons Exploration (MMX) is a robotic space probe designed to bring back the first samples from Mars’ largest moon, Phobos. It is developed by the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), with collaboration from NASA, ESA and CNES who provide scientific instruments. The U.S. contributes a neutron and gamma-ray spectrometer, while the European contribution includes a near-infrared spectrometer and expertise in flight dynamics to plan the mission’s orbiting and landing manoeuvres. Launched in 2024 and arriving in 2025, MMX lands and collects around 10 g (0.35 oz) of samples from Phobos, along with conducting Deimos flyby observations and monitoring Mars’ climate. It provides evidence to explain the origins of the Martian moons, while also yielding information useful to future crewed missions. The samples are returned to Earth by 2029.* In addition to its spectrometers, the spacecraft includes multiple cameras and a dust monitor. Other missions to Phobos take place this decade – including a Russian attempt to repeat the ill-fated Fobos-Grunt probe and a sample-return effort by ESA called Phootprint.

Credit: NASA/JAXA

2025-2028

Contact with the Voyager probes is lost

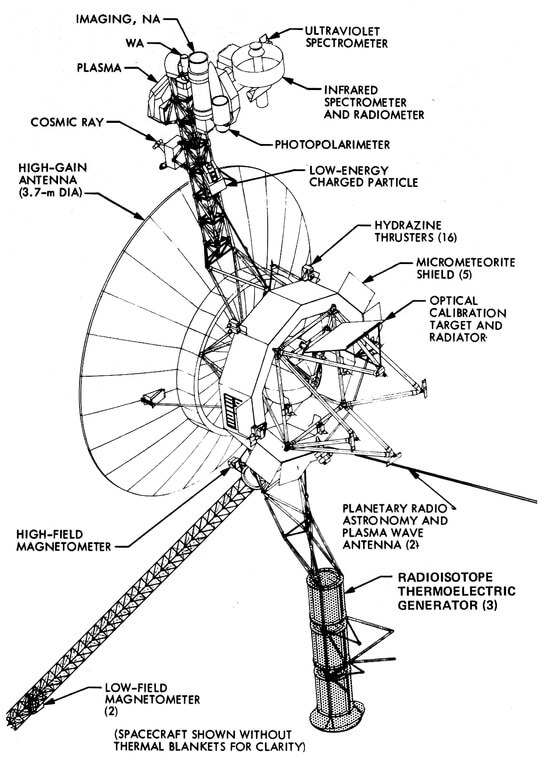

Voyager

I is the farthest man-made object: 14 billion miles (22 billion km) away, or 150 times

the distance between the Sun and Earth. Both Voyager I and its sister probe, Voyager II, have remained operational for nearly half a century, continuing to transmit

data back to NASA. They have left the heliosphere and

are now headed towards the Oort Cloud. By 2025, however, onboard power is finally starting to wane.*

During 2017, Voyager I had fired its trajectory thrusters for the first time since November 1980, to subtly rotate the spacecraft and reorient its antenna – extending the mission lifetime slightly. This makes Voyager II the first of the two to shut down, with Voyager I outliving it by three years.* The shutdowns happen gradually rather than instantly, with instruments failing one by one, until none are left operating.

Each probe

carries a gold-plated audio-visual disc, in the event that either spacecraft

is ever found by intelligent alien life. The discs carry images of Earth

and its lifeforms, a range of scientific information, along with a medley,

“Sounds of Earth”, that includes the sounds of whales, a baby

crying, waves breaking on a shore, music from different

cultures and eras, plus greetings in 60 different languages. Voyager I passes by the red dwarf star Gliese 445 in the year 42,000 AD and Voyager II approaches Sirius in 298,000 AD.

2025

The ITER experimental fusion reactor is switched on

ITER (originally the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor) is a prototype fusion power plant constructed in France. The most complex machine ever created by humans, it aims to become the first project of its kind to demonstrate efficient and economic use of fusion reactions – the same processes occurring naturally within the Sun.

While human-made

fusion had been achieved briefly and on small scales in the past, these tests resulted in a net loss of energy. By contrast, ITER is designed to produce a plasma that releases the equivalent of 500 megawatts (MW) of power, during much longer pulses than any previous machine.

Built at a cost of €22 billion (US$26.1 billion), over a period of nearly two decades, ITER is among the biggest science projects ever undertaken, second

only to the International Space Station. This joint research experiment

is funded by countries including China, the European Union (EU) members, India, Japan, Russia, South Korea and the United States.

To demonstrate

net fusion power on a large scale, the reactor core is required to simulate conditions

at the centre of the Sun. For this, it uses a magnetic confinement device

known as a tokamak. This doughnut-shaped vacuum chamber generates a powerful

magnetic field that prevents heat from touching the reactor’s walls.

Tiny quantities of fuel are injected into and trapped within the chamber.

Here they are heated to 100 million degrees, forming a plasma. At such

high temperatures, the light atomic nuclei of hydrogen become fused

together, creating heavier forms of hydrogen such as deuterium and tritium.

This releases neutrons and a huge amount of energy.

The ITER project began in 1988, with many years of conceptual and engineering studies prior to site preparation in 2007. Tokamak complex excavation commenced in 2010 and construction of the tokamak itself followed later in the decade. The assembly and integration phase got underway in 2018 with finishing of the concrete supports and bottom parts of the cryostat. The official announcement of “machine assembly” marked a key milestone in 2020 and this led to installation of the vacuum vessel (16 times as heavy as any previous fusion vessel) and central solenoid (the superconducting coil for producing 13.5 teslas). When completed in 2025, the ITER contains more than 10 million individual parts, weighing more than 25,000 tons and connected by 200 km (124 miles) of superconducting cables, all kept at –269°C (–452°F) by the world’s largest cryogenic plant.

The end of assembly is followed by operational activation and first plasma in 2025.* The initial experiments pave the way to full deuterium–tritium fusion beginning in the mid-2030s.* ITER achieves a Q-value of 10. In other words, the input of 50 MW results in an output of 500 MW; a substantial net gain in production of energy. ITER can sustain this in bursts of nearly 20 minutes. For comparison, the Joint European Torus (JET) in 1997 – the previous world record for peak

fusion power – required 24 MW to produce an output of only 16 MW (a net loss and Q-value of 0.67), which lasted just a few seconds.

The insights resulting from experiments at ITER lead to new ways of holding plasma in

place at critical densities and temperatures. Further development and refinement of chamber designs, such as better superconducting magnets

and advances in vacuum systems, improves the generation of power required

for sustained commercial operations. This is demonstrated by ITER’s successor, in the mid-21st century, which takes an input of 80 MW and produces an output of 2,000 MW (a Q-value of 25). In the second half of the 21st century, electricity produced by fusion becomes widely available – offering humanity a new and virtually unlimited supply of

clean, green energy.

Credit: ITER/Jamison Daniel, Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility

A billion human genomes have been sequenced

DNA testing is now so cheap, fast and routinely accessible that over a billion human genomes have been sequenced around the world. Back in 1990, when the first attempt was made to identify and map all 3.3 billion base pairs in a person – an effort known as the Human Genome Project – the cost of doing so ran into billions of dollars. The time required was over a decade and involved many scientists from all over the globe in what became the largest ever collaboration on a biological project.

In the years following the completion of the Human Genome Project, tremendous improvements were made in sequencing times and costs. These new techniques allowed many more individuals to have their DNA read. The cost per genome fell by orders of magnitude – from $100 million by 2001, to under a million dollars by 2008, less than $10K by 2011 and just $1,000 by 2016. This was a trend even faster than Moore’s Law.

DNA sequencing began to enter the mainstream in the second half of the 2010s. In the United Kingdom, for example, the National Health Service (NHS) offered its first medical diagnoses via genetic testing in 2015 and three years later had completed the 100,000 Genomes Project. Similar initiatives were attempted in many other regions, as the benefits of large-scale health databases became clear. The increasing portability and availability of consumer testing kits, such as those offered by 23andMe, led to a further acceleration of this trend. Initially restricted to partial scans, it was now technically and financially viable to conduct whole genome sequencing to provide a full and complete analysis of an individual’s DNA. As well as future health risks and personalised treatments, information could also be gleaned about their ancestry and family history.

By 2025, a billion human genomes have been sequenced – about one-eighth of the world’s population.* The quantity of genomic data is now reaching into the exabyte scale,* larger than the video file content of the entire YouTube website. This has created huge demand for improved storage capacities and led to a surge in cloud computing networks. The sheer volume and complexity of Big Data has made AI programs such as IBM’s Watson far more commonly used for medical and research purposes. Among the latest discoveries are thousands of genes for intelligence,* providing new insights and targets for the treatment of impaired cognitive abilities. With around 75% of a person’s IQ attributed to genetic differences,* these genes will play a role in creating super-intelligent humans in the more distant future.

While great progress is now being made in genetics, there are privacy and security implications of so much health information being generated and stored online. Various hacking scandals involving theft and selling of personal data have made the news headlines recently. Insurance firms and others with vested interests, particularly in the U.S., are keen to exploit the treasure trove of medical information now available and have stepped up their lobbying efforts. There is growing concern about the injustice of genetic prejudice and discrimination.

Human

brain simulations are becoming possible

The first complete simulation of a single neuron was perfected in 2005. This was followed by a neocortical column with 10,000 neurons in 2008; then a cortical mesocircuit with 1,000,000 neurons in 2011. Mouse brain simulations, containing tens of million of neurons, were later achieved.

By 2025, the exponential

growth of data has made it possible to form accurate models

of every part of the human brain and its 100 billion neurons.** Between

2000 and 2025, there was a millionfold increase in computational

power, together with vastly improved scanning resolution and bandwidth. Much like the Human Genome Project, there were many in the scientific community who doubted that the brain could be mapped so quickly. Once again,

they failed to account for the exponential (rather than linear) growth of information technology.

Although it’s now possible to scan and map a complete human brain down to the neuron level, analysing the enormous volumes of data it contains and using that to fully understand its workings will take much longer. Nonetheless, this represents a major milestone in neurology and leads to increased funding towards various brain-related ailments.

Credit: Sergey Nivens

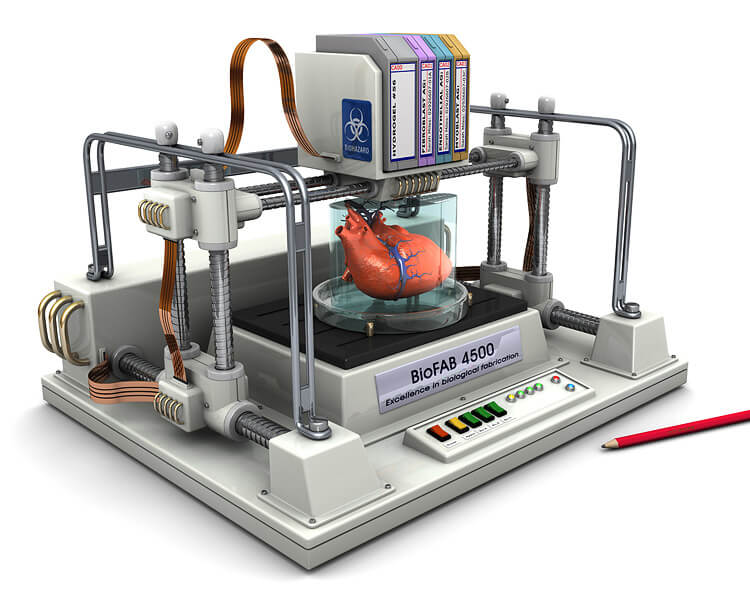

3D-printed human organs

Additive manufacturing, also known as 3D printing, was first developed in the mid-1980s. Initially used for industrial applications such as rapid prototyping, it fell dramatically in cost during the 2010s and 2020s, becoming available to a much wider audience.*

Arguably the most transformative breakthroughs were occurring in health and medicine. Customised, 3D-printed body parts were saving peoples’ lives and included artificial jaw bones,* bioresorbable splints for breathing* and replacement skull parts,* among many other uses. Non-critical applications included dental implants* and exoskeletons to assist with mobility and joint movement.*

Even greater advances were taking place, however. 3D printing was no longer limited to inorganic materials like polymers or metals. It was being adapted to construct living, biological systems. Layer after layer of cells, dispensed from printer heads, could be placed exactly where needed with precision down to micrometre scales. Initially demonstrated for simple components like blood vessels and tissues,** more sophisticated versions later emerged in combination with scaffolds to hold larger structures in place. Eventually, the first complete organs were developed with sufficient nutrients, oxygen and growth vectors to survive as fully-functioning replacements in mouse models.

By 2025 – after testing on animals – customised 3D-printing of major human organs is becoming feasible for the first time.** Although yet to be fully perfected (as certain types of organs remain too complex), this is nevertheless a major boost for life extension efforts. In the coming decades, more and more of the 78 organs in the human body will become printable.*

Credit: ExplainingTheFuture.com

Vertical

farms are common in cities

With a total population fast approaching 8 billion, world food demand has continued to climb. At the same time, however, the increasingly dire effects of climate change, as well as other environmental factors, are now having a serious impact. Droughts, desertification and the growing unpredictability of rainfall are reducing crop yields in many countries, while shrinking fossil fuel reserves are making large-scale commercial farming ever more costly. Decades of heavy pesticide use and excess irrigation have also played a role. The United States, for example, has been losing almost 3 tons of topsoil per acre, per year. This is between 10 and 40 times the rate at which it can be naturally replenished – a trend that, if allowed to continue, would mean all topsoil disappearing by 2070.* As this predicament worsens and food prices soar, the world is now approaching a genuine, major crisis.*

Amid the deepening sense of urgency and panic, a number of potential solutions have emerged. One such innovation has been the appearance of vertical farms. These condense the enormous resources and land area required for traditional farming into a single vertical structure, with crops being stacked on top of each other like the floors of a building. Singapore opened the world’s first commercial vertical farm in 2012.* By the mid-2020s, they have become widespread, with most major urban areas using them in one form or another.*

Vertical farms offer a number of advantages. An urban site of just 1.32 hectares, for example, can produce the same food quantity as 420 hectares (1,052 acres) of conventional farming, feeding tens of thousands of people. Roughly 150 of these buildings, each 30 stories tall, could potentially give the entire population of New York City a sustainable supply of food.* Genetically modified crops have increased in use recently* and these are particularly well-suited to the enclosed, tightly-controlled environments within a vertical farm. Another benefit is that food can then be sold in the same place as it is grown. Farming locally in urban centres greatly reduces the energy costs associated with transporting and storing food, while giving city dwellers access to fresher and more organic produce.

Another major advantage of vertical farming is its sustainability. Most structures are primarily powered on site, using a combination of solar panels and wind turbines. Glass panels coated in titanium oxide cover the buildings, protecting the plants inside from any outside pollution or contaminants. These are also designed in accordance with the floor plan to maximise natural light. Any other necessary light can be provided artificially. The crops themselves are usually grown through hydroponics and aeroponics, substantially reducing the amount of space, soil, water and fertiliser required.

Computers and automation are relied upon to intelligently manage and control the distribution of these resources. Programmed systems on each level control water sprayers, lights and room temperature. These are adjusted according to the species of plant and are used to simulate weather variations, seasons and day/night cycles. Some of the more advanced towers even use robots to tend to crops.* Excess water lost through evapotranspiration is recaptured via condensers in the ceiling of each level, while any runoff is funnelled into nearby tanks. This water is then reused, creating a self-contained irrigation loop. Any water still needed for the system can be filtered out of the city’s sewage system.

Vertical farms also offer environmental benefits. The tightly controlled system contained in each structure conserves and recycles not just water – but also soil and fertilisers such as phosphorus, making the total ecological footprint orders of magnitude smaller than older methods of agriculture. On top of that, the reduced reliance on arable land helps to discourage deforestation and habitat destruction. Vertical farms can also be used to generate electricity, with any inedible organic material transformed into biofuel, via methane digesters.

Credit: Chris

Jacobs, Gordon Graff, Spa Atelier

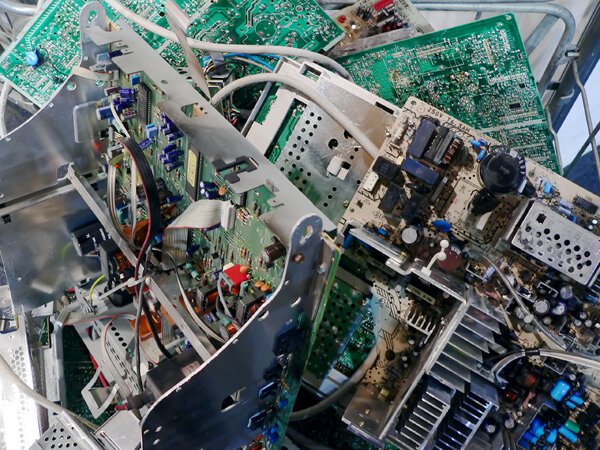

Solid waste is reaching crisis levels

Solid waste has been accumulating in urban areas and landfills for many decades. Poor funding for waste disposal and lack of adequate recycling measures, together with population growth and associated consumption have ensured a never-ending rise in trash levels. The global output of solid waste has risen from 1.3 billion in 2012,* to over 2.2 billion tons annually by 2025.* The cost of dealing with this quantity of garbage has nearly doubled as well, rising to $375 billion annually.

Developing nations, lacking the money and infrastructure to properly dispose of their trash, face the greatest crisis, with solid waste increasing five-fold in some regions. Public health is being seriously affected, since groundwater is becoming more and more polluted as a result. E-waste is proving to be even more damaging. In India, for example, discarded cellphones have increased eighteen-fold.* Rapid advances in technology, ever-more frequent upgrades to electronic products, and the aspiration for Western lifestyles have only exacerbated this situation.

Developed nations are better able to handle the problem, but since only 30% of their waste is recycled it continues to build rapidly. Plastics are a particular problem, especially in oceans and rivers, since they require centuries to fully degrade.* As well as direct environmental damage, this waste is releasing large amounts of the greenhouse gas methane, which contributes to global warming.* Public activism, though increasing at this time, has little effect in halting the overall trend.

Kivalina has been inundated

Kivalina was a small Alaskan village located on the southern tip of a 7.5 mi (12 km) long barrier island. Home to around 400 indigenous Inuit, its people survived over countless generations by hunting and fishing. During the late 20th and early 21st centuries, a dramatic retreat of Arctic sea ice left the village extremely vulnerable to coastal erosion and storms. The US Army built a defensive wall, but this was only a temporary measure and failed to halt the advancing sea. By 2025, Kivalina has been completely abandoned, its small collection of buildings disappearing beneath the waves. The Alaska region has been warming at twice the rate of the USA as a whole, affecting many other Inuit islands. At the same time, opportunities are emerging to exploit untapped oil reserves made available by the melting ice.*

Completion of the East Anglia Zone

The United Kingdom, one of the best locations for wind power in the world, greatly expanded its use of this energy source in the early 21st century – offshore wind in particular. With better wind speeds available offshore compared to on land, offshore wind’s contribution in terms of electricity supplied could be higher, and NIMBY opposition to construction was usually much weaker. The United Kingdom became the world leader in offshore wind power when it overtook Denmark in 2008. It also developed the largest offshore wind farm in the world, the 175-turbine London Array.

As costs fell and technology improved, various new projects got underway. By 2014, the United Kingdom had installed 3,700MW – by far the world’s largest capacity – more than Denmark (1,271MW), Belgium (571MW), Germany (520MW) the Netherlands (247MW) and Sweden (212MW) combined. Growing at between 25 and 35 per cent annually, the United Kingdom’s offshore wind capacity was on track to reach 18,000MW by 2020,* enough to supply one-fifth of the country’s electricity.

The largest of these projects, known as “Dogger Bank”, was built off the northeast coast of England in the North Sea. This gigantic installation featured 600 turbines covering an area the size of Yorkshire* and generating 7,200MW from the early 2020s. Eight other major sites were being planned around the United Kingdom* with potential for up to 31,000MW.

Among the biggest of these other sites was the East Anglia Zone. This was divided into six separate areas, each with 1,200MW capacity for a combined total of 7,200MW – the same as Dogger Bank. Each turbine would have a rotor diameter of 200m, and a tip height up to 245m. The first stage received planning permission in 2014 and was operational by 2019,* providing a clean, renewable energy source for 820,000 homes. The remaining five stages were approved between 2016 and 2020,* followed by a similar schedule for construction. When fully completed in 2025, the whole East Anglia Zone would supply a total of four million homes.

With ongoing concerns over energy and climate change, offshore wind capacity in the United Kingdom continued to grow rapidly in subsequent decades. Eventually it became integrated into a continent-wide “supergrid” stretching across Europe.* This was followed by “peak wind” in the late 21st century* as the resources utilised offshore reached a theoretical maximum of 2,200 GW* – though alternative energies such as fusion had arrived by then.*

Click to enlarge

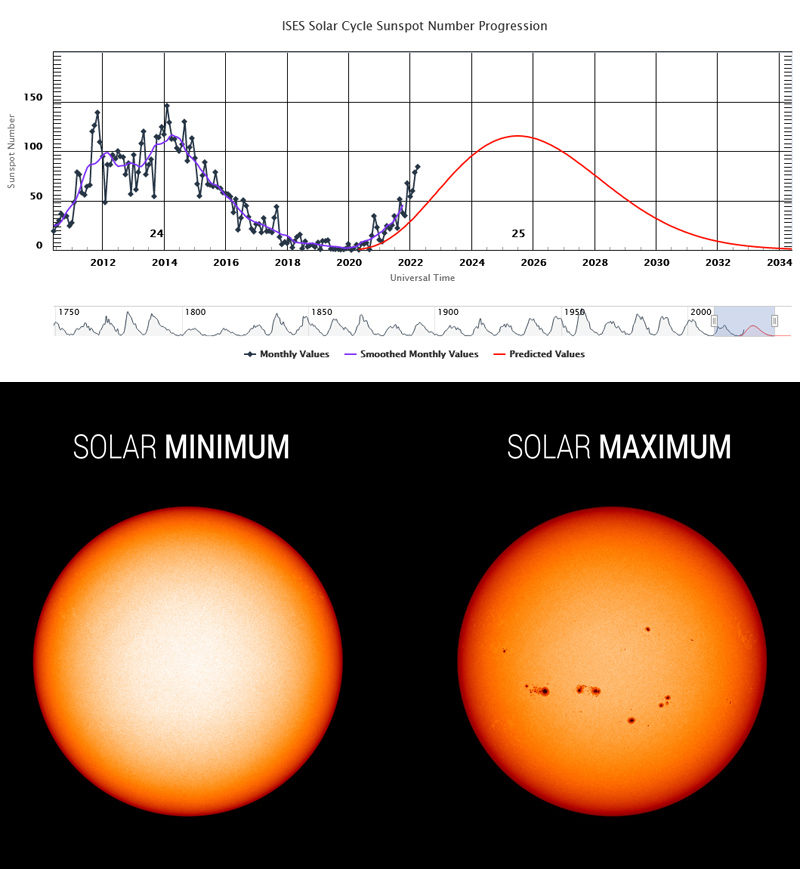

The

next solar maximum

The solar cycle is a periodic change in the Sun’s activity, measured by the number of sunspots on its surface. The magnetic field of the Sun is flipped during each solar cycle, with a flip occurring when the sunspot cycle is at its maximum. Levels of solar radiation, ejections of solar material, the number and size of sunspots, solar flares, and coronal loops all exhibit a synchronised fluctuation, from active to quiet to active again. On average, the solar cycle takes about 11 years to go from one solar maximum to the next, with duration varying from 8 to 14 years. After two sunspot cycles, the Sun’s magnetic field returns to its original state.

In late 2019, the Sun entered Solar Cycle 25, the 25th cycle since record-keeping began in 1755. The peak of this cycle occurs in mid-2025.* The number of sunspots is greater than had been earlier predicted, but the cycle is still weaker than the historical average. Solar Cycle 10, for example, produced the most intense geomagnetic storm ever recorded, in what became known as the Carrington Event of 1859. This created strong auroral displays around the world and even sparked fires in telegraph stations, likely the result of a coronal mass ejection colliding with Earth’s magnetosphere.

Solar Cycle 25 ends during the early 2030s. The prospect of future geomagnetic storms of similar magnitude to the Carrington Event remains a topic of debate among scientists, who urge governments to prepare for disruption to electrical grids and satellite communications. Such events are predicted to occur every 100 to 200 years.

Credit: NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory/Joy Ng/NOAA

The

European Extremely Large Telescope is operational

This

revolutionary new telescope is built in Cerro Armazones, Chile, by the European Southern Observatory (ESO), an intergovernmental research organisation supported by fifteen countries. It has the aim of observing the

universe in greater detail than even the Hubble Space Telescope.

The main mirror

is 39 metres (129 ft). This makes it powerful enough to directly image exoplanets, study their atmospheres, and potentially detect water and organic molecules in protoplanetary disks around stars. It can also perform “stellar archaeology”

– measuring the properties of the first stars and galaxies, alongside probing the nature of dark matter and dark energy.

Originally planned for 2018, the observatory was delayed until 2022 due to financial problems, then delayed again until 2025.* The mirror is also reduced in size slightly, having previously been 42m.

Credit: ESO

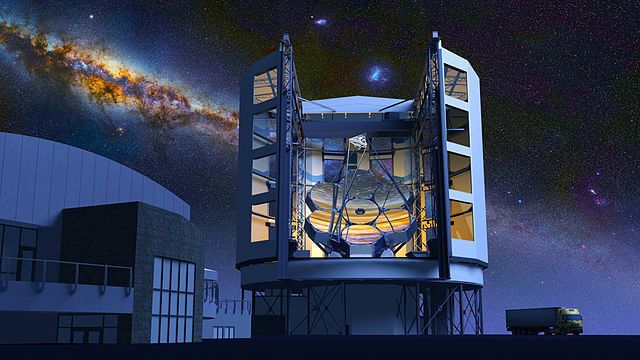

The Giant Magellan Telescope is fully operational

The Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT) is a major new astronomical observatory completed in 2025.* Costing around $1 billion, this international project is led by the US, in partnership with Australia, Brazil, and Korea, with Chile as the host country. The telescope is built on a mountain top in the southern Atacama Desert of Chile with an altitude of 2,516 m (8,255 ft). This site was chosen as the instrument’s location because of its outstanding night sky quality and clear weather throughout most of the year, along with a lack of atmospheric pollution and sparse population giving it low light pollution.

The GMT consists of seven 8.4 m (27.6 ft) diameter primary segments, with a combined resolving power equivalent to a 24.5 m (80.4 ft) mirror. It has a total light-gathering area of 368 m sq (3,960 sq ft), which is 15 times greater than the older, neighbouring Magellan telescopes. It is 10 times more powerful than the Hubble Space Telescope.

The GMT operates at near infrared and visible wavelengths of the spectrum. It features adaptive optics, which helps to correct image blur caused by the Earth’s atmospheric interference. The first of the seven mirrors was cast in 2005, with polishing completed to a surface accuracy of 19 nanometres, rms. By 2015, four of the mirrors had been cast and the mountain top was being prepared for construction.

The GMT achieves first light in 2024, with full operational capability in 2025.* It is just the latest in a series of major telescopes being constructed around this time, heralding a new era of higher resolution astronomy. Others include the Thirty Metre Telescope (2024), the European Extremely Large Telescope (2025), and the Square Kilometre Array (2027), in addition to numerous space-based observatories. This new generation of telescopes leads to huge advances in knowledge of the early universe, major new discoveries of Earth-like planets around other stars, and breakthroughs in understanding the mysterious dark matter and dark energy that influence the structure and expansion of the universe.

By Giant Magellan Telescope – GMTO Corporation [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

The first test flight of the Skylon spaceplane

Until now, all spacecraft launching from Earth into space have used multiple stages. This has required jettisoning parts of a launch vehicle while in flight, in order to reduce weight. During the 2020s, however, a new reusable spaceplane is developed that can operate without the need for booster rockets, fuel tanks, engines or other external components – instead utilising a single stage, hybrid jet/rocket system.*

Known as Skylon, the vehicle is designed by Reaction Engines Limited, a British aerospace manufacturer based in Oxfordshire, England, with funding provided by the UK government, European Space Agency and BAE Systems. The total program cost was projected to be £7.1 billion ($10.1 billion), with a unit cost of about £190 million ($270 million). BAE Systems acquired a 20% stake in the company during 2015, investing an initial amount of £20.6 million ($29.4 million) to develop the engine system.

Skylon takes off from a specially strengthened runway. It uses a precooled jet engine (rather than scramjet) to reach speeds of Mach 5.5 (1,700 m/s) at 26 km (16 miles) altitude using oxygen in the atmosphere to “breathe”. This provides a significant reduction in propellant consumption. It then closes the air inlet and operates as a highly efficient rocket to complete the remainder of its journey to orbit, 300 km (186 miles) above the Earth. This concept is known as the Synergetic Air-Breathing Rocket Engine (“SABRE”).*

Although its payload capacity is only 15 tons (about 1/3rd that of the Space Shuttle), each plane is cheaper (about 1/10th) and vastly more fuel efficient than earlier spacecraft, largely thanks to the reduced weight offered by the SABRE. After completing a mission, it reenters the atmosphere with its skin protected by a strong ceramic, landing back on the runway like a normal aeroplane. It then undergoes any necessary maintenance and is capable of flying again in just two days (compared to two months for the Space Shuttle).

Ground-based tests of the SABRE engine commence in 2019. The first unmanned test flights were originally planned for 2020, but subsequently faced delays until 2025.* Although initially crewless, the Skylon is later used to carry astronauts to and from space stations. Future versions are even capable of being adapted for space tourism, transporting up to 30 passengers in a purpose-built module and costing under $500,000 per person. Skylon is hailed as the biggest breakthrough in aerospace propulsion technology since the invention of the jet engine – revolutionising access to space.* It also leads to commercial airliners capable of travelling around the globe in under four hours.

Skylon in flight. Credit: Reaction Engines

The first manned flights from Russia’s new spaceport

Despite being a major space power, Russia for decades lacked its own proper independent space launch facility for manned flights. Instead it was reliant on the Baikonur Cosmodrome in neighbouring Kazakhstan – leased from the government of that nation until 2050, at a cost of $115 million per year.

In 2011, construction began on the Vostochny Cosmodrome, a new spaceport located in the Amur Oblast region in Russia’s Far East. This was intended to reduce Russia’s dependency on Kazakhstan, enabling most missions to be launched from its own soil. The area devoted to this new infrastructure would be nearly 100 sq km (39 sq mi) with four separate launch pads, an airport, train station, academic campus, training and space tourism facilities, business centres and a town of 30,000 capacity for housing workers and their families.*

Roscosmos had suffered a number of setbacks and launch failures in the 2000s and early 2010s, including the loss of its Phobos-Grunt probe. To address this issue and restore the nation’s reputation in space, Vladimir Putin announced a major boost in funding; a budget of 1.6 trillion rubles ($51.8 billion or €39 billion euros) for 2013-2020, a far greater increase than any other space agency in the world.

Nevertheless, the spaceport faced delays. The first manned flights had been scheduled for 2018,* but were subsequently put back until 2025. Plans for the launch vehicle were also revised to incorporate a new craft with a two-stage, heavy-lift Angara A5B rocket, instead of the older Soyuz. Russia is now beginning a moon exploration program based on this modernised launch vehicle.*

Credit: Roscosmos

High-speed

rail networks are being expanded in many countries

By the mid-2020s, many countries have radically overhauled their rail transport infrastructure, or are in the process of doing so.

In Spain,

more than 10,000km of high-speed track has been laid, making it the

most extensive network in the world. 90 percent of the country’s population

now live within 50 km of a bullet train station.*

In Britain, the first phase of a major high-speed rail line is nearing completion. This will travel

up the central spine of the country – connecting London with England’s next largest city, Birmingham. It will eventually be expanded to Manchester and the north. Trains will be

capable of reaching 250 mph, slashing previous journey times.*

In Japan,

Tokyo will soon be connected with Nagoya via superfast magnetic levitation trains. Tests conducted in

previous decades showed that it was possible to build a railway tunnel

in a straight route through the Southern Japanese Alps. The first generation

of these trains already held the world speed record, at 581 km/h (or

361 mph); but recent advances in carriage design have pushed this still

further, to speeds which are fast enough to compete

with commercial airliners.*

Many other

countries are investing in high-speed rail during this time, due to

its speed and convenience. Even America – which for decades had neglected its rail network – is now making big

*

Source: Federal

Railroad Administration

A comprehensive overhaul of the U.S. airspace system is complete

The final upgrades of the Next Generation Air Transportation System (NextGen) are completed this year. This has involved a complete overhaul of the existing air transport network. Many aspects of the National Airspace System (NAS) had been failing because of a reliance on largely obsolete technology. The navigation system, for example, which relied on ground-based radar beacons, was based on technology from the 1940s.

NextGen brings pervasive upgrades and improvements to the entire system during the 2010s and early 2020s. This includes physical infrastructure as well as computer systems. Hundreds of new ground-based stations are built to allow satellite surveillance coverage of nearly the entire country. New safety and navigation procedures are introduced that markedly reduce flight times, while offering a more dynamic method of air traffic control.

Advances in computer power and digital communication have produced what is now a far more integrated and efficient national system. One of the largest technical advances is the complete replacement of the previous radar navigation system with a modern, GPS-based version. This creates detailed, three-dimensional highways in the sky, and takes into account variations in topography and weather – enabling pilots to fly shorter, more precise routes. By 2018, this system was in place at every major US airport.

Once on the runway, taxiing planes are guided by automated systems. These use data gathered on the position of every other plane and vehicle to present pilots and controllers with detailed, real-time traffic maps of the tarmac. Runway capacity is increased with the introduction of multiple take-off and landing pathways, as opposed to the older, single route approach.

Overall, these upgrades offer substantial improvements in flight-times, air pollution and fuel consumption. Delays are reduced by nearly 40%, saving tens of billions of dollars. Over 1.4 billion gallons of fuel are saved and CO2 emissions are cut by 14 million metric tons. These numbers will continue to improve steadily over the years.*

Aircraft themselves are evolving in form, function and efficiency. A number of striking new designs have emerged with significant technological and environmental benefits.*

The global crowdfunding market reaches $100bn

Crowdfunding is a form of alternative finance that involves raising monetary contributions from a large number of people – usually online – to collectively fund a project or venture. It first emerged in the arts and music communities, before eventually spreading into other areas. The rise of social media allowed it to gain popular and mainstream use. In 2009, crowdfunding generated slightly under a billion dollars worldwide, but by 2016 this had expanded 20-fold. Some of the biggest platforms now available were Gofundme, Indiegogo, Kickstarter, Patreon and Teespring.

With even greater potential yet to be fully realised, crowdfunding saw ongoing, rapid growth in the late 2010s and into the 2020s.* Further momentum was gained from the billions of new Internet users appearing online (from 1.7 billion in 2010 to 5 billion by 2020), with social media continuing to play a major role. China was now the largest market, representing half the global total, followed by the rest of East Asia. By 2025, the crowdfunding market has reached almost $100bn worldwide* – roughly 1.8 times the size of the global venture capital industry a decade earlier.

Crowdfunding enables creators to attain low-cost capital from people around the world, reaching untapped markets. It also creates a forum to engage with audiences in the production process via updates and sharing of feedback. Pre-release access to content, or the opportunity to beta-test products, can be offered to project backers as part of the funding incentives. Fraud is also reduced through standards-based crowdfunding platforms.

The democratisation of fundraising through crowdfunding is a major breakthrough for entrepreneurs and non-profit organisations, allowing them to outmanoeuvre larger companies and corporations. Some of the more ambitious projects being crowdfunded include satellites and space probes.

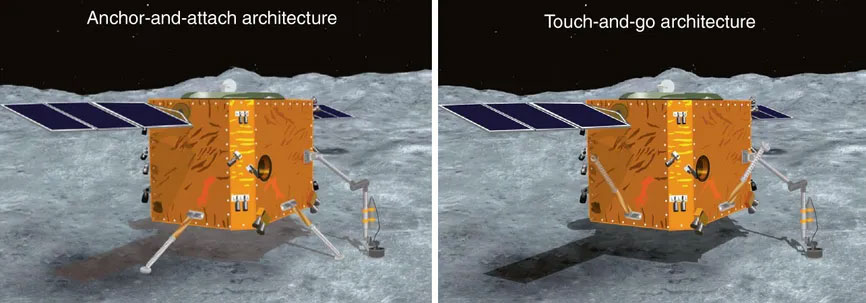

Sample return mission to Kamo’oalewa

In 2025, China conducts a sample return mission to the near-Earth asteroid 469219 Kamoʻoalewa.* This tiny, fast-rotating body is just 41 m (135 ft) in diameter and is the smallest, closest, and most stable (known) quasi-satellite of Earth. Its orbit, and the lunar-like silicates it contains, make it likely to be an impact fragment from the Moon. The mission provides confirmation of this along with further science data when it returns its sample a year later.

The technical challenges include entering and keeping orbit around a small body with very weak gravity. The spacecraft requires long-life propulsion engines and a high-precision navigation, guidance, and control system. The return capsule must also withstand ultra-high-speed re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere.

China develops two mission architectures – “anchor-and-attach” and “touch-and-go” – using both to maximise the chances of success. It lands on the asteroid using four robotic arms, with a drill on the end of each for anchoring.

After delivering samples to Earth in a return capsule, the probe continues on towards the main-belt comet 311P/PANSTARRS. On arrival in 2034, it uses a variety of imaging, spectrometer, and other instruments to investigate whether such a comet may have delivered water to the young Earth. It also provides insight into the differences between active asteroids and classic comets.*

Credit: Tao Zhang, Kun Xu, and Xilun Ding/Nature Astronomy

BepiColombo arrives in orbit around Mercury

BepiColombo is a joint mission between the European and Japanese space agencies. It is only the third mission to study Mercury at close range and only the second to enter into orbit around the planet. Consisting of a rocket component and two science probes, the mission is launched in 2018. It performs a total of nine flybys around Earth, Venus and Mercury before orbital insertion on 5th December 2025.* It is the most comprehensive on-location study of Mercury ever performed, with 12 specific objectives:

- What can be learned from Mercury about the composition of the solar nebula and the formation of the planetary system?

- Why is Mercury’s normalised density markedly higher than that of all other terrestrial planets, Moon included?

- Is the core of Mercury liquid or solid?

- Is Mercury tectonically active today?

- Why does such a small planet possess an intrinsic magnetic field, while Venus, Mars and the Moon do not have any?

- Why do spectroscopic observations not reveal the presence of any iron, while this element is supposedly the major constituent of Mercury?

- Do the permanently shadowed craters of the polar regions contain sulphur or water ice?

- Is the unseen hemisphere of Mercury markedly different from that imaged by Mariner 10?

- What are the production mechanisms of the exosphere?

- In the absence of any ionosphere, how does the magnetic field interact with the solar wind?

- Is Mercury’s magnetised environment characterised by features reminiscent of aurorae, radiation belts and magnetospheric substorms observed at Earth?

- Since the advance of Mercury’s perihelion was explained in terms of space-time curvature, can we take advantage of the proximity of the Sun to test general relativity with improved accuracy?

The European contribution, Mercury Planetary Orbiter (MPO), studies the surface and internal composition, while the Japanese probe, known as the Mercury Magnetosphere Orbiter (MMO), analyses the magnetosphere and atmosphere. A new form of ion engine is used for the propulsion system. BepiColombo was originally planned for a 2014 launch with 2020 arrival at Mercury, but faced a number of delays. The mission concludes in 2028.

Direct flights from Sydney to London and New York

In 2025, Australia’s national airline, Qantas, begins offering Project Sunrise flights.* This new service – described as “the final frontier of long-haul travel” – enables direct routes from cities in eastern and southern Australia to any major city in the world, without any connections.

In the case of Sydney to London, the journey lasts for 20 hours, making it the world’s longest commercial passenger flight. However, this enables a reduction in travel time of up to four hours compared with earlier services that required layovers.

Qantas began operating non-stop flights from the western port city of Perth to London in March 2018. This ended the era of the continents of Europe and Oceania not being connected by non-stop flights, marking the first time that all continents, excluding Antarctica, had been connected by non-stop flights. The Sydney to London service is one of the final steps in a century of progress for air travel distances. Qantas had carried its first passenger in 1922 aboard an Avro 504 biplane on a domestic flight within Queensland. Sydney to London journeys in 1935 took 12 days, made up of 31 stopovers.

Project Sunrise includes 12 new Airbus A350-1000s, which begin entering service in late 2025; the fleet is fully operational by 2028. They each have a seat count of 238, the lowest compared with any other A350-1000 in service. The interior designs, influenced by medical and scientific research, are specially configured for improved comfort on ultra-long-haul flights, which includes a Wellbeing Zone and more spacious seating in both Premium and Economy cabins.* HEPA filters remove 99.9% of particles and refresh the air every 2-3 minutes. As part of its 2050 net zero emissions commitment, Qantas announced that all net emissions from Project Sunrise flights would be carbon offset.

References

1 Will automation lead to fewer jobs in 10 years? Short answer, yes., Institute for the Future:

http://www.iftf.org/future-now/article-detail/will-automation-lead-to-fewer-jobs-in-10-years-probably-yes/

Accessed 14th June 2015.

2 We’ve reached a tipping point where technology is now destroying more jobs than it creates, researcher warns, Business Insider:

http://uk.businessinsider.com/technology-is-destroying-jobs-and-it-could-spur-a-global-crisis-2015-6

Accessed 14th June 2015.

3 Harold Meyerson: Technology and trade policy is pointing America toward a job apocalypse, Washington Post:

http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/harold-meyerson-technology-and-trade-policy-is-pointing-america-toward-a-job-apocalypse/2014/03/26/ba331784-b513-11e3-8cb6-284052554d74_story.html

Accessed 14th June 2015.

4 Raising America’s Pay: Why It’s Our Central Economic Policy Challenge, Economic Policy Institute:

http://www.epi.org/publication/raising-americas-pay/

Accessed 14th June 2015.

5 Why Wages Won’t Rise, Robert Reich:

http://robertreich.org/post/107998491550

Accessed 14th June 2015.

6 Eric Schmidt Just Revealed A Key Truth About The Economy That Very Few Rich Investors And Executives Want To Admit …, Business Insider:

http://www.businessinsider.com/eric-schmidt-on-inequality-2014-1?IR=T

Accessed 14th June 2015.

7 Ultra-fast, the robotic arm catches objects on the fly, YouTube:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M413lLWvrbI

Accessed 14th June 2015.

8 Disney teaches a humanoid robot to play catch and juggle balls, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2012/11/24-2.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

9 Robot hand is unbeatable against a human opponent, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2012/06/27.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

10 Industrial Robot Wields A Blade Like A Master Swordsman, Vocativ:

http://www.vocativ.com/video/tech/machines/industrial-robot-wields-a-blade-like-a-master-swordsman/

Accessed 14th June 2015.

11 Table tennis: man vs machine, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2014/03/10.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

12 Beer-pouring robot programmed to anticipate human actions, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2013/05/30.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

13 Robots that can touch and feel?, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2012/06/24.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

14 Robot masters new skills through trial and error, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2015/05/28.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

15 Watson (computer), Wikipedia:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Watson_%28computer%29

Accessed 14th June 2015.

16 AI software can identify objects in photos and videos at near-human levels, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2014/11/21.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

17 New AI program interacts like a human, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2014/10/6.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

18 Computer program recognises emotions with 87% accuracy, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2014/08/24-2.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

19 Cloud computing platform for robots launched, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2013/03/12-2.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

20 Artificial intelligence breakthrough: CAPTCHA ‘Turing Test’ is passed, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2013/10/29-2.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

21 “…robotics and artificial intelligence will permeate wide segments of daily life by 2025, with huge implications for a range of industries such as health care, transport and logistics, customer service, and home maintenance.”

See AI, Robotics, and the Future of Jobs, Pew Research:

http://www.pewinternet.org/2014/08/06/future-of-jobs/

Accessed 14th June 2015.

22 Self-driving trucks are going to hit the US economy like a human-driven truck, Quartz:

http://qz.com/417014/self-driving-trucks-are-going-to-hit-the-us-economy-like-a-human-driven-truck/

Accessed 14th June 2015.

23 “Daimler and other manufacturers, including Nissan and Tesla, are planning to introduce fully autonomous vehicles (with no human driver on board) during the early 2020s.”

See The first licenced autonomous driving truck in the US, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2015/05/7.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

24 Autonomous Vehicles Will Replace Taxi Drivers, But That’s Just the Beginning, Huffington Post:

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/sam-tracy/autonomous-vehicles-will-_b_7556660.html

Accessed 14th June 2015.

25 See 2024-2064.

26 Rethink Robotics aims to revolutionise manufacturing with humanoid robot, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2012/09/18.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

27 Boeing’s new robots outperform human workers, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2013/06/4.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

28 See 2016.

29 A robot to help improve agriculture and wine production, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2015/01/30.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

30 Affordable robotics in agriculture, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2013/09/3.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

31 Robot cleaner can empty bins and sweep floors, New Scientist:

http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg22630213.200-robot-cleaner-can-empty-bins-and-sweep-floors.html

Accessed 14th June 2015.

32 First drone delivery company gains approval in the U.S., Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2019/04/27.htm

Accessed 5th January 2020.

33 “Amazon Prime Air” will use drones for 30 minute delivery, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2013/12/2.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

34 Hospital robot kills 95% of pathogens in 5 minutes with UV light, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2013/01/22.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

35 Robotic butlers to appear in hotels, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2014/08/14.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

36 Robot check-in: The hotel concierge goes hi-tech, BBC:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-32931923

Accessed 14th June 2015.

37 World’s first robotic kitchen to debut in 2017, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2015/04/18.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

38 CIROS, the salad-making robot, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2012/11/3.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

39 Autonomous swarm boats to defend U.S. Navy, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2014/10/6-2.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

40 The human rights implications of killer robots, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2014/05/13.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

41 Latest videos of the ATLAS, LS3, and WildCat robots, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2013/10/4.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

42 See 2047.

43 See 2016.

44 OSHbot – a new automated retail assistant, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2014/10/30-3.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

45 Crime-predicting robot to patrol streets from 2015, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2013/12/11.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

46 Microsoft Shows Off Robot Security Guards, PC Magazine:

http://uk.pcmag.com/robotics-automation-products/37736/news/microsoft-shows-off-robot-security-guards

Accessed 14th June 2015.

47 Amazon warehouse robots, YouTube:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=quWFjS3Ci7A

Accessed 14th June 2015.

48 It takes human researchers 12 years “to do what this robot can do in a week.”, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2013/11/13.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

49 Solar power prices to continue falling through 2025, experts say, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2012/12/14.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

50 Lowering the cost of solar installation with robots and cleaning technology, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2013/10/16-2.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

51 Meet Shanice, the new holographic receptionist, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2013/08/21.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

52 Holograms to replace people at New York airports, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2012/05/28.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

53 See 2014.

54 Amazon to open checkout-free store in NYC, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2018/09/13.htm

Accessed 22nd August 2019.

55 Automation arrives at restaurants (but don’t blame rising minimum wages), Computer World:

http://www.computerworld.com/article/2837810/automation-arrives-at-restaurants-but-dont-blame-rising-minimum-wages.html

Accessed 14th June 2015.

56 Burger-making machine could replace human workers, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2012/12/1-3.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

57 Rise of robot reporters: when software writes the news, New Scientist:

http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn25273-rise-of-robot-reporters-when-software-writes-the-news.html

Accessed 14th June 2015.

58 IBM forms Watson Group to meet growing demand for cognitive innovations, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2014/01/9-2.htm

Accessed 14th June 2015.

59 3D Printing Market by Offering (Printer, Material, Software, Service), Process (Binder Jetting, Direct Energy Deposition, Material Extrusion, Material Jetting, Powder Bed Fusion), Application, Vertical, Technology, and Geography – Global Forecast to 2024, Markets and Markets:

https://www.marketsandmarkets.com/Market-Reports/3d-printing-market-1276.html

Accessed 1st January 2020.

60 See 2039.

61 See 2024.

62 World Development Indicators, World Bank:

http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators

Accessed 14th June 2015.