It’s time to look back at the cult heroes, mullets, flashes in the pan, quality imports and recruits who bombed in the 1990s.

In the second instalment of the 60 rugby league players who explain the 1990s, it’s time to go beyond the teams and positions to the real memorable characters.

If you missed yesterday’s first edition, it detailed the players who represent each of the 24 clubs who kicked a ball in anger during the controversial decade as well as the nine stars who dominated each position on the field.

Anyone who has listened to the podcast, 60 Songs That Explain The 90s will know how hard it is to sum up such a weird and wonderful period, particularly for those who weren’t around to witness the madness.

It’s the same trying to explain a rugby league decade when the traditionally Sydney-based competition had welcomed in three new interlopers in 1988 and then exploded with four new franchises in 1995.

These 60 players will always be part of the Australian rugby league history books and in one way or the other, are indelibly linked to the 1990s.

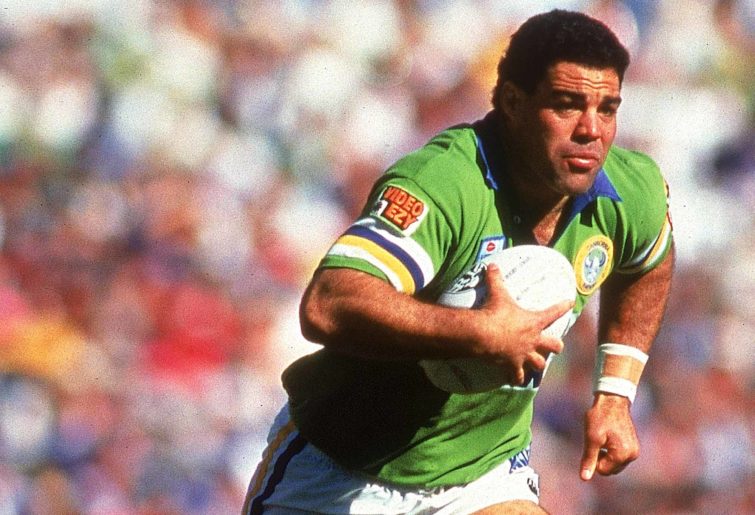

Mal Meninga (Photo by Getty Images)

The characters of the ‘90s: Simply The Rest

The Captain: Mal Meninga was a colossus for Canberra, Queensland and Australia. His presence was immense on any team he led. Although he was not as quick as his younger years in the ‘90s, he still more than held his spot in all the representative line-ups into his final year in 1994 at age 34, saying farewell with a successful sign-off as he became the only player to go on four Kangaroo tours.

The Most Talented: Brad Fittler had the sidestep, the speed, the ability to kick off either boot. He was simply a nightmare for opposition defenders whether he was at centre, five-eighth or lock. He had no peer when it came to natural ability in the ‘90s.

The Try-scorer: Steve Menzies gets the nod here not because he scored the most tries, his 104 was well behind Steve Renouf, but because he was a forward who actually averaged roughly the same per season: around 14: as The Pearl from his 1994 debut onwards. Andrew Ettingshausen (103) and Michael Hancock (101) were the only other centurions for tries in the 1990s.

The Goal-kicker: Jason Taylor actually landed the most with 788 at 74.7% even though Matthew Ridge with Manly and the Warriors had the better strike rate at 80.2% from his 580 goals and Daryl Halligan racked up 767 at 78.5%.

The Point-scorer: Daryl Halligan gets his recognition here for his tally of 1830 in the ‘90s which was well clear of Taylor’s 1760 and Ridge’s 1331. Raiders forward David Furner (1218), Panthers centre Ryan Girdler (1052) and Steelers winger Rod Wishart (1010) were the only other players to crack a thousand for the decade.

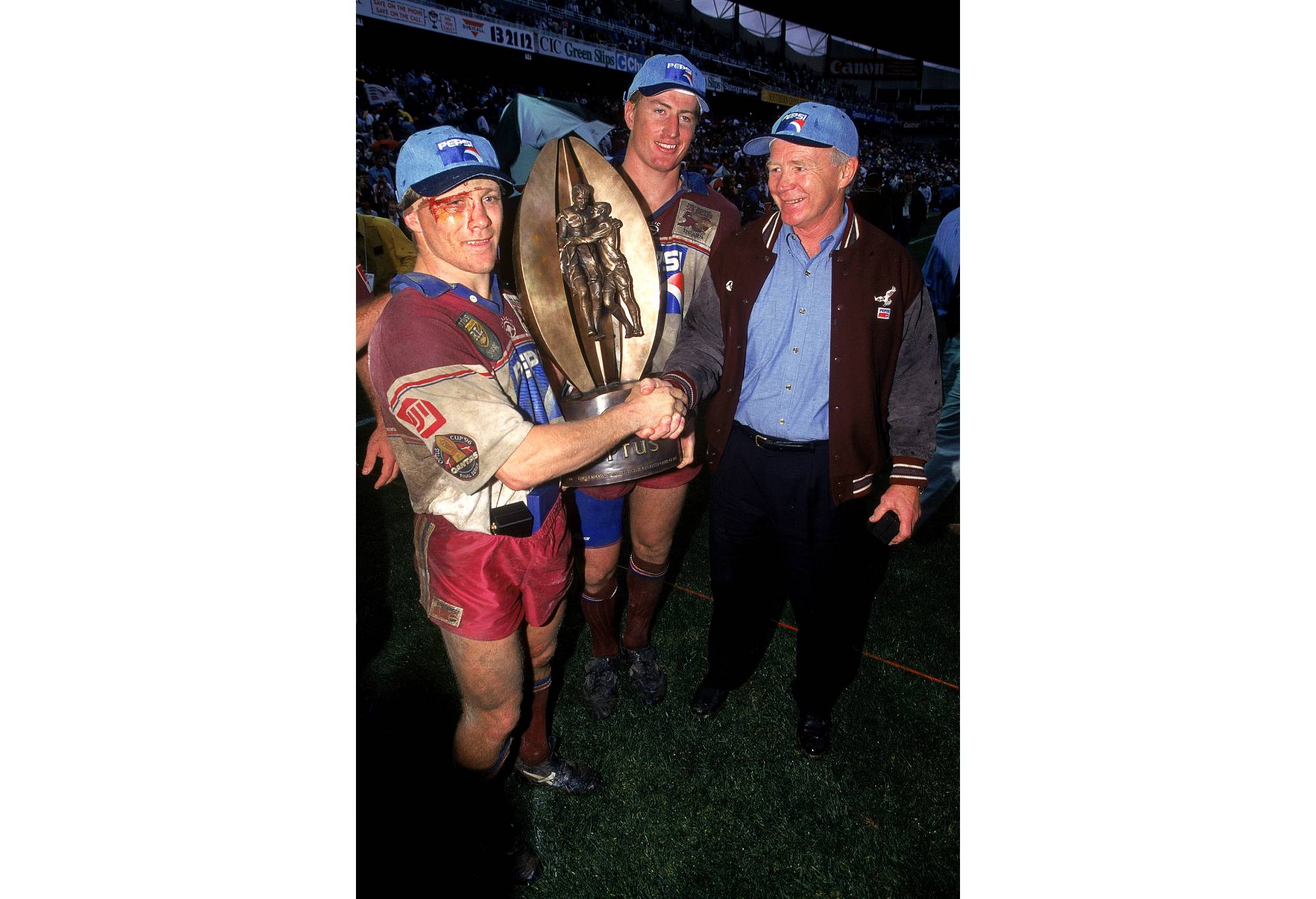

The Toughest: Geoff Toovey was always the smallest player on a field of physically imposing humans and not only did he never take a backward step, he sent many opponents scurrying in reverse with his upending tackles. Never forget he got stomped in the face by Adam MacDougall in the 1997 ARL Grand Final but despite the pain and a stream of blood, he got bandaged up and played out the match. The previous year when Manly won the game he also finished swathed in bandages but at least got to raise the trophy that time to ease the pain.

Geoff Toovey, Steve Menzies and Bob Fulton after the ARL Grand Final in 1996. (Photo by Getty Images)

The Biggest Hitter: David Gillespie was known as “Cement” after being called a “cement head” as an insult but the nickname was most appropriate for the force he dished out in tackles. A powerful combination of size and timing, he left countless players both short of breath and the will to run at him again.

The Best Defender: Trevor Gillmeister was not big compared to other forwards, but he used his upward thrust in tackles to cut down the tallest timber and it’s no coincidence that he’s become the go-to guy for coaches who want to teach this generation how to stop a defender in their tracks.

The Fastest: Lee Oudenryn has to be the example of the 90s speedster: it’s there to see in the footage of the match race against England’s finest, Martin Offiah, bursting off the goal line to blitz across the Parramatta Stadium turf in the biggest boilover of the era apart from Buster Douglas knocking out Mike Tyson.

The British import: Ellery Hanley was the best English player to strut their stuff in Australia in the 1990s but he was past his prime during his two-year stint with Balmain. It was not a great decade for UK recruits: they were either very brief like Jonathan Davies, Martin Offiah and Gary Connolly or underwhelming like Lee Jackson and Denis Betts.

The Rugby convert: Matthew Ridge was the best of the era where rugby converts started to dry up as the 15-player code went professional. Ridge made an immediate impact from the moment he arrived at Manly in 1990 and not just his goal-kicking but his play at fullback was critical to the Sea Eagles building towards their three-year domination in the middle of the decade.

The Best Kiwi: Gary Freeman made his name at Balmain in the late 1980s before becoming the first New Zealander to win the Dally M Medal in 1992 during his first year at the Roosters.

The Origin bolter: Ben Ikin was beyond a bolter when he was chosen for the 1995 State of Origin series, he was pretty much the last man standing. After the majority of Queensland-eligible players had been snapped up by the Super League to have a red line put through them at the selection table, Ikin had played just three games for the Gold Coast as an 18-year-old but was given a chance on the bench. And despite famously not recognising him when he lobbed into camp, coach Paul Vautin gave him more than just token game time and Ikin scored a match-sealing try in game three to complete what will eternally be the most unlikely clean sweep in Origin history.

The journeyman: Darrien Doherty was a relatively anonymous back-rower who bounced around from Penrith (1990) to Wests (93-94), the Bulldogs (95), Steelers (96), Mariners (97), Rams (98) and Cowboys (99-2000) to set a record for playing first grade at seven clubs which has since been equalled by Tyran Smith and Blake Green. If he kept the jerseys from the 90s, he’d have quite the colourful wardrobe.

The rookie sensation: Andrew Johns in 1994 not only broke records as a rookie but he gave Newcastle fans optimism that they now had a true star, a home-grown whizz-kid who could give their hard-working team that something special to compete with the Sydney sides. Johns scored 23 points in his Round 1 debut – a record which still stands – and finished the season with 162 to kick off a career which would end with two premierships and Immortal status.

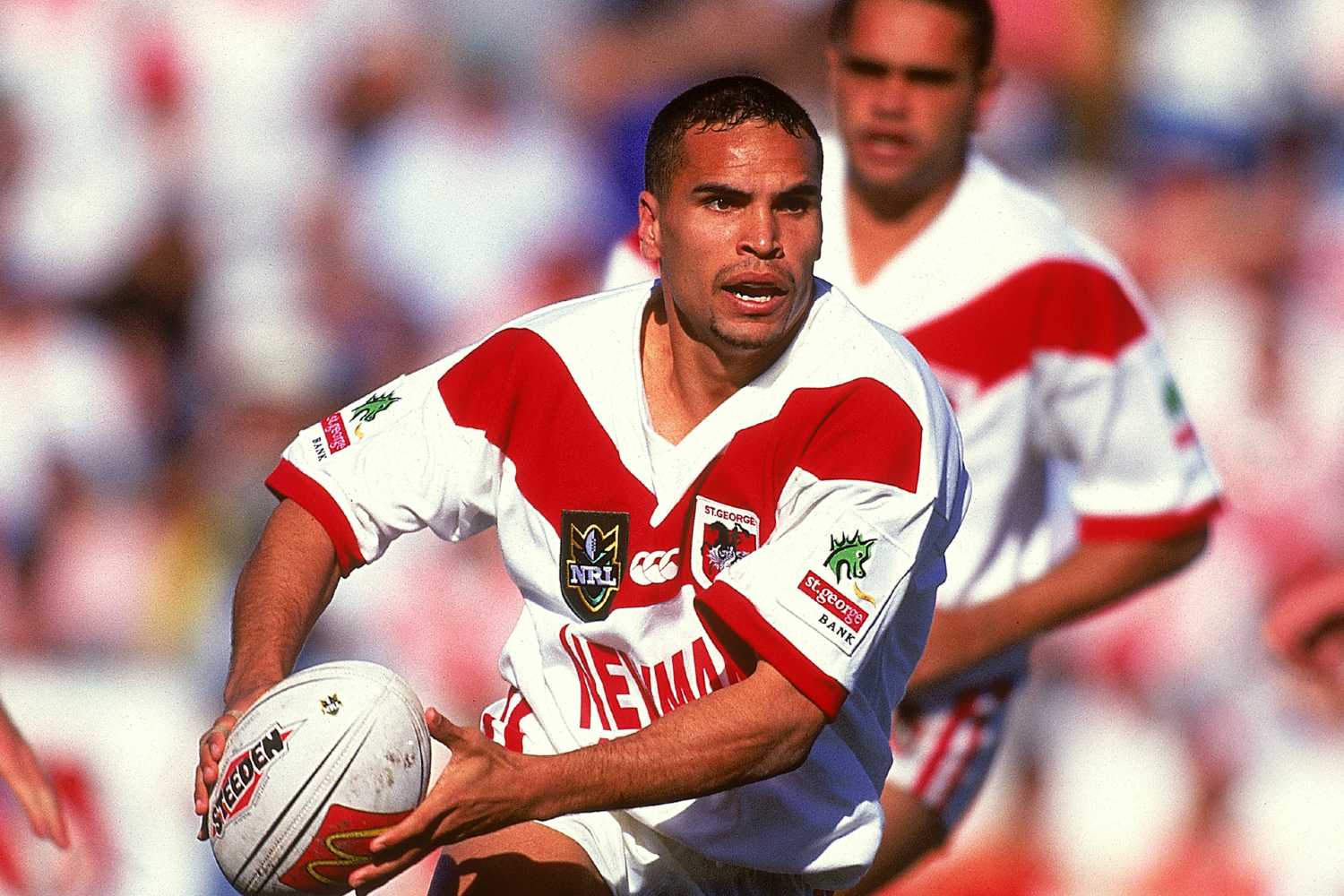

The human headline: Anthony Mundine was a magnet for attention on and off the field. Fans loved his brilliance at five-eighth for St George, Brisbane and St George Illawarra and he was not afraid to back up his efforts by talking up his efforts and his team. In explaining his move back to the Dragons after being stuck in the centres at the Broncos, his response was he wanted to be “The Man”. The nickname stuck and unfortunately for league fans, he quit the sport early in 2000, disillusioned at missing out on representative teams to what he considered inferior rivals.

Anthony Mundine of the Dragons looks to offload the ball during a NRL finals match between the St George Dragons and the Canterbury Bulldogs at Kogarah Oval in Sydney, Australia. (Photo by Nick Wilson/Getty Images)

The hard-luck story: Brett Papworth was a fine five-eighth with the Wallabies in 15 Tests but his three seasons at the Roosters ended in 1991 after he suffered knee injuries, a broken arm as well as a badly busted jaw while trying to tackle the tree trunks that masqueraded as the thighs of Steelers winger Rod Wishart.

The signing that bombed: Garrick Morgan was another Wallaby who played 24 Tests and was considered the then amateur code’s biggest star on the rise when poached by the South Queensland Crushers for their inaugural campaign in 1995. But while his towering frame was handy in the lineout and scrum, it was not built for the demands of rugby league and he only managed two games in the top grade before returning to union when it was lifting its ban on players who had taken the money from the pro ranks, reclaiming his place in the Test team.

The flash in the pan: Paul Hauff, after playing 18 games in his rookie season, had a spectacular 1991 in which he became Queensland’s fullback for all three Origins and made his Test debut. The lanky Broncos fullback looked like he was destined for a lengthy career at the top but injuries and the emergence of Julian O’Neill at Brisbane meant he only played another 19 first-grade games before hanging up the boots at the end of 1996.

The icon: Ian Roberts made history when he came out as the first openly gay professional rugby league player, earning plaudits and respect for being true to himself. He had already established himself as a fearsome competitor at club level with Souths and Manly and with NSW and Australia in the representative arena but the bravery he showed off the field continues to be a source of inspiration for people of all walks of life today.

The mullet: Tawera Nikau took the business at the front and party at the back look to a new level when the Kiwi forward arrived at Cronulla midway through the 1990s. The unmistakable Nikau shock of black hair was flying all over the place in the ‘99 grand final as he hurtled into the St George Illawarra side to spark Melbourne’s astonishing second-half surge to victory.

The moustache: Gary Belcher hung onto his mo well in the 1990s at a time when the glory days of the Dennis Lillee era were long gone. Unlike these days where every player seems to experiment with some sort of moustache, beard or something in between, Belcher was part of a small group in the ‘90s who defied the trend like Wally Lewis and Cliff Lyons.

The What-If Story: Phil Clarke came to the Roosters in 1995 as the English Test captain keen to show he could mix it in the Australian competition but his career was cut short two games into the following season when the back-rower suffered a fracture in his neck against North Queensland. If not for that injury, the Roosters’ rise to grand finalists in 2000 may have arrived a little earlier.

The wizard: Cliff Lyons deserves to be in his own category because he was truly unique. A smoker and self-confessed lazy trainer, he did not possess great athleticism but his game smarts were second to none as he would keep the defence guessing as he meandered in a seemingly innocuous fashion across the field before hitting a runner with precision passing at the perfect time. The emergence of Steven Menzies in 1994 gave Lyons a late-career boost as the back-rower had a very happy knack of bursting through the holes created by the ageless Manly five-eighth, who retired in 1999 a few weeks shy of his 38th birthday.

The guy you didn’t want to fight: Les Davidson was a throwback footballer to an era when throwing hands was almost as important as the rest of a forward’s game. The reputation of “Bundy” was enough to mean most opponents didn’t get into a fight with the big Rabbitohs and Sharks enforcer but the few who did, quickly learned the power of his big left duke. Well, they did when they eventually regained their consciousness.

The cult hero: Ian Herron, aka “Chook”, is a still fan favourite among old-school Dragons and Eels supporters. The excitable winger, who played in St George’s grand final defeats in 1992 and ‘93, earned an enormous following from the punters for his bizarre stance when kicking for goals when he would virtually turn his back to the ball before his run-up. He finished his career as an international, lining up for Ireland at the 2000 World Cup.

The accidental hero: Craig Smith: It’s fitting that the last scoring play of the 1990s was perhaps the most memorable, even if the player involved couldn’t remember what happened at the time. Smith, the unfashionable Storm winger, collected a kick to score the winning try in the 1999 grand final but was clocked high by Dragons opponent Jamie Ainscough in the Melbourne player’s last act as an NRL player. Bill Harrigan awarded the penalty try, Matt Geyer kicked the premiership-winning conversion and Smith cemented one of the most unlikely places in rugby league folklore.

Hat tip to the rugbyleagueproject for being the best source of data for statistical career retrospectives.