Growing up, every Saturday morning while my school friends were out shopping, going to drama school or learning to dive at the local swimming pool, I would put on my shalwar kameez and head to my mosque’s weekend school. There, I would sit cross-legged on prayer mats with other young girls, our heads covered with soft chiffon scarves, listening intently to stories from Islamic history, before catching up on school gossip and that week’s Top of the Pops.

I was seven when I started going to the school in Bradford, and 15 when I left. It was the 1980s, and there were about 20 of us. Our parents all knew each other, most of the congregation was of Pakistani heritage, and most of the children second generation. We learned the basics of the Islamic faith, how to offer prayer in Arabic with English translation, how to read the Qur’an, and what being a Muslim required of us. We had sports days and speech competitions, went swimming and learned to cook. We navigated two cultures, and languages, weaving together English and Urdu.

Sign up to our Inside Saturday newsletter for an exclusive behind-the-scenes look at the making of the magazine’s biggest features, as well as a curated list of our weekly highlights.

It made a change from my Catholic girls’ school, where the syllabus was gospel, sacraments, and Christ through the eyes of Christianity. The supplementary school helped me find answers to some of the questions my friends asked about being Muslim. Growing up with two faiths gave me clarity. While Islam respects all prophets, little is taught about Jesus in the mosque. My secondary school gave me insight into the foundations of British holidays and traditions, in a way that connected with Islam.

-

Orot supplementary school at Edgware & Hendon Reform Synagogue, London. Top: Sammy, nine, dressed as Harry Potter. Above left: Rachel, three, who also wears a Little Red Riding Hood Purim cap that once belonged to her mother. Above right: Sam, nine, joined Orot when he was in reception. ‘I have nice friends there. The work is challenging but fun. Today, I am handling a Burmese python. They are constrictors, so it could squeeze me, and eat me whole’

During the year, we’d have regional competitions where girls and young women would come together to give speeches on topics such as “cleanliness is next to godliness” and “Islam and the rights of women”, recite the Qur’an in Arabic, sing religious songs and take part in quizzes. We’d pack into a coach and travel down the M1 to London for a two-day event where we’d compete against girls from similar backgrounds from other parts of the country. We all spoke Urdu, but it was our English accents that revealed where we were really from – Bradford, Glasgow, Gillingham or Manchester. The women making the announcements were always Pakistani aunties, and even now place names such as Walthamstow and Redbridge are converted to a particular pronunciation in my head.

Supplementary schools are common to a variety of cultures. Photographer Craig Easton has spent several months travelling across the UK, documenting students at Saturday and Sunday schools, ranging from a Japanese school in Livingston to a school in Buckinghamshire for children of African heritage. “There are hundreds of these schools, full of British kids who want to celebrate their family heritage and culture,” he says. “Some of the schools are faith schools, and others are about ‘this is the country you came from, and this is the political background to the place’.”

Easton, an award-winning photographer, has a thread running through his work: the idea that it is possible to be British and still hold on to one’s heritage. He is keen for his images to be an antidote to the rise of rightwing nationalism. “Photography and journalism are so good at shining light into dark corners, but I wanted to turn that around and say how brilliant some things are across the country. These are kids with thick Mancunian or Scottish accents celebrating their Japanese culture or their Polish culture. They are all deeply connected to the culture or faith, while also being deeply British.”

Easton said he was received well by all the schools. “The children had enormous pride in their cultural identity, and it was celebratory. That’s what I loved about it.” One of the groups he visited was a Polish school in Aylesbury. After Poland joined the EU in 2004, the community in the UK began to grow. Four years later, the Aylesbury Saturday school was set up by the local Polish community as a means of holding on to their traditions and language. “There was a real sense of longing,” Michalina Skierkowska, head of the school, tells me. “People missed their family, the culture, the food and the reality of being in Poland.” Since then, hundreds of children, from reception age to GCSE, have passed through the school, which is funded by the Polish government and membership fees, supplemented by fundraising activities.

-

Polish Saturday School, Aylesbury. Top: Marcel, six. Above: Rosie, seven, who was born in London

“Education through the Polish school isn’t just about broadening your horizons and learning the language and culture and everything else – it gives you that sense of security that, any time you want to go back, the door is always open,” Skierkowska says. The children learn about Polish culture, food and history, as well as about the Catholic faith. They have the opportunity to learn to read and speak Polish. Many of the children take a GCSE in the language, but the skills they gain also help them stay connected with family back home.

“Having to grow up facing harsh realities, postwar, I remember my sisters had to queue in the shops because there was no food available, and we had to learn to grow produce and cook from scratch,” Skierkowska says. “It gave us a strong work ethic. We want to make sure our children have the same resilience, and they are patriotic about the country.”

-

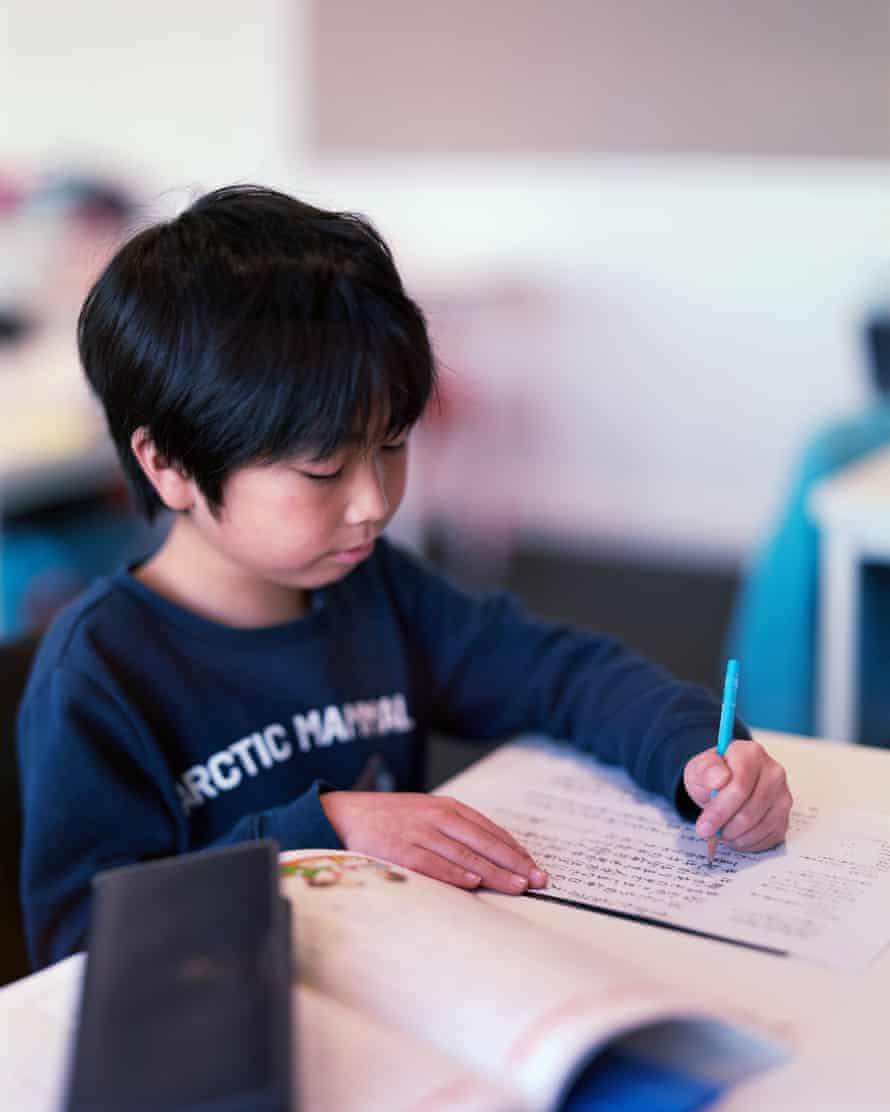

Scotland Japanese School, Livingston. Top: Hikari, 14 – her mother is Japanese, her father Scottish. ‘I really like the fact that we follow the same curriculum as schools in Japan. In the library there are good manga books.’ Above left: Kenji, eight – both of his parents are Japanese. Above right: Liam, eight; his mother is Japanese, his father Australian. ‘I have been in the Japanese school for five years. I have to learn lots of spellings, which is very challenging for me. Break time is the best. I try to have fun with my friends’

Teachers at other supplementary schools are similarly passionate about their mission. Yuko Hirono is on the committee of the Scotland Japanese school. Children have been coming to the Saturday school in Livingston from Glasgow, Edinburgh and other parts of the country for 40 years. There are currently 95 students, aged five to 15, who spend three hours every Saturday morning studying Japanese literature. Hirono found out about the school when she moved to Scotland 10 years ago with her five-year-old daughter. “The programme was for the Japanese expat community, initially, but at the moment there are more children from mixed marriages.”

They learn how to write and read in Japanese, although, Hirono says: “The level of learning isn’t quite the same as it is in Japan. They learn to write Chinese characters and Japanese characters, and read and discuss Japanese novels. We also have calligraphy classes, sports days and a graduation ceremony done in the way it is in Japan.”

-

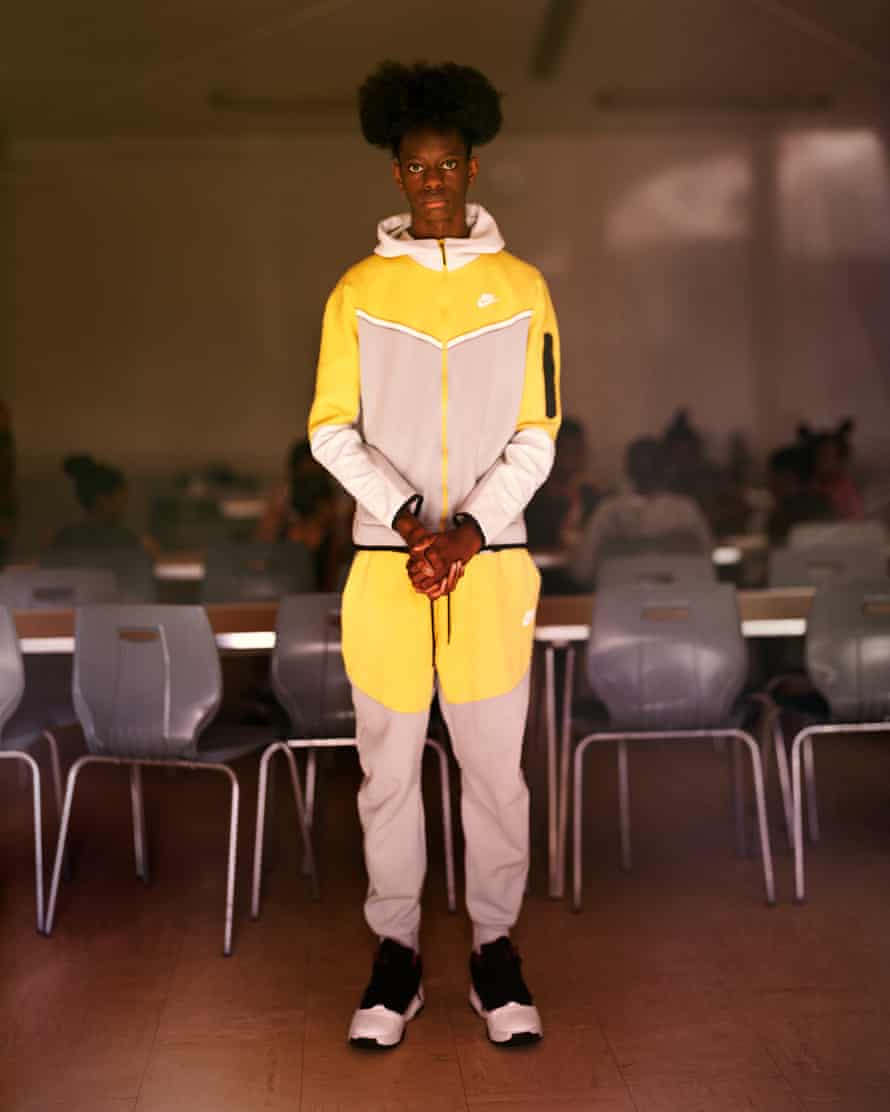

Akacia complementary school, High Wycombe. Top: Hannah, 12. ‘I come here for 3.5 hours on Saturday mornings during term times. I love the maths classes. Mr Katumwa, the teacher, thinks that if I continue to work hard, I may be able to take my GCSE early.’ Above left: Yolissa, nine. ‘One of the adults in the background is my dad, who is a voluntary teacher. I love being with the friends I’ve made here – we’re like a big family. We call our teachers Auntie and Uncle.’ Above right: Jayden, 16. ‘I’m in a senior maths class with children of mixed abilities. There is no dress code; we are encouraged to wear whatever makes us feel comfortable’

The school has an impressive library of about 4,000 Japanese books, many of which were donated by parents of former students who have since returned to Japan. It is funded by Scottish Development International, a subsidy from the foreign ministry of Japan, and grant money from Japanese companies in Scotland; it has recently applied for charity status. “Funding has been a crucial issue,” Hirono says. “Running the school is quite a hard job for parents. But they all greatly appreciate the Japanese school. It’s like a ‘little Japan’, a small community where you speak your own language, even swap homemade Japanese foods. There is a great spirit of mutual aid.”

-

Hadaf Persian School, London. Above left: Alma, 16, taking part in a traditional dance from Iran. ‘We’ve performed it every year since I joined the school. It’s done to celebrate the harvest, and the colours are all about standing out – none of our costumes match. Because everyone at the school is from the same place, we understand each other, the language we speak, our shared background. I feel very at home.’ Above right: Kiara, seven, who also has an older sister at the school

On the other side of the UK, in High Wycombe, is Further south, in High Wycombe, is the Akacia complementary school. The idea of an African school was revived 25 years ago by Kojo Asare Bonsu. “As an African parent, I was concerned. Every year I read that our so-called Black Caribbean children, especially our boys, weren’t functioning and benefiting from the British education system. So five of us decided that we would restart the Saturday school. The original school was started here in the UK among Africans who came out of the British colonies in the 1960s. Grandparents, parents, mothers and fathers were concerned about the narrative and the biases that were connected to the whole issue of us, as African people, being able to comprehend and embrace high culture.”

-

‘Nicolae Iorga’ Romanian School, Wirral. Above left: Luca, eight, was born in Bucharest and has attended the school since it opened in 2018. This picture was taken on the first day back after a Covid-enforced period of online learning; to celebrate, the children wore Romanian dress and a rosette with the colours of the Romanian flag. Above right: Daria, seven, and Alexandra, five, moved to the UK recently. Daria particularly enjoys art, Romanian stories and making puppet shows

Hundreds of primary school-aged children have passed through Akacia’s doors. They are taught maths and English, the history of Africa and its people, alongside “self-respect, self-esteem and self-worth”, says Bonsu. “We have inspirational speakers. In March, we had a visit from Paul Obinna, the creator of the African timeline, a poster that presents 8,000 years of history. In May we’re going to have African board games, and in June we’re going to have African storytelling and then, just before the close of term, African drumming.”

-

Saint Stanislaw Kostka Polish School, Aberdeen. Aurelia, 10, was born in Aberdeen and has been at the school for a year: ‘I’m learning a lot about our literature and traditions. We learn through fun – I like to dress up and take part in competitions’

Bonsu is passionate about the work his school is doing, and my own experiences tell me he is right to be. It’s been more than 30 years since I left my Saturday school, and while I didn’t always appreciate being torn away from the telly on a weekend, the experience did give me a strong sense of identity. Being around young women who matched all my cultural, social and religious intersections meant I didn’t feel like an anomaly. At times when Islamophobia or racism have raised their head, I’ve been equipped to deal with it, and able to differentiate between religion and culture.

The girls from the mosque school have remained a constant in my life. It was a place of shared experiences, strong friendships and figuring out what we wanted, as much as what we didn’t.