Cathy Keifer | Getty

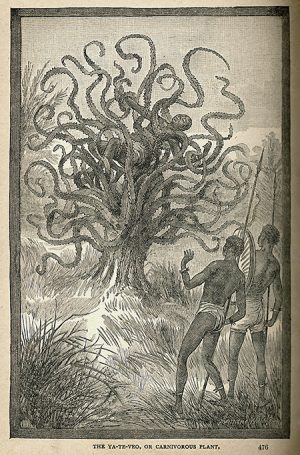

Toward the end of the 19th century, lurid tales of killer plants began popping up everywhere. Terrible, tentacle-waving trees snatched and swallowed unwary travelers in far-off lands. Mad professors raised monstrous sundews and pitcher plants on raw steak until their ravenous creations turned and ate them too.

The young Arthur Conan Doyle stuck closer to the science in a yarn featuring everyone’s favorite flesh-eater, the Venus flytrap. Drawing on brand-new botanical revelations, he accurately described the two-lobed traps, the way they captured insects, and how thoroughly they digested their prey. But even his flytraps were improbably large, big enough to entomb and consume a human. Meat-eating, man-eating plants were having a moment, and for that you can thank Charles Darwin.

Until Darwin’s day, most people refused to believe that plants ate animals. It was against the natural order of things. Mobile animals did the eating; plants were food and couldn’t move—if they killed, it must only be in self-defense or by accident. Darwin spent 16 years performing meticulous experiments that proved otherwise. He showed that the leaves of some plants had been transformed into ingenious structures that not only trapped insects and other small creatures but also digested them and absorbed the nutrients released from their corpses.

In 1875, Darwin published Insectivorous Plants, detailing all he had discovered. In 1880, he published another myth-busting book, The Power of Movement in Plants. The realization that plants could move as well as kill inspired not just a hugely popular genre of horror stories but also generations of biologists eager to understand plants with such unlikely habits.

Today, carnivorous plants are having another big moment as researchers begin to get answers to one of botany’s great unsolved riddles: How did typically mild-mannered flowering plants evolve into murderous meat-eaters?

J.W. Buel

Since Darwin’s discoveries, botanists, ecologists, entomologists, physiologists, and molecular biologists have explored every aspect of these plants that drown prey in fluid-filled pitchers, immobilize them with adhesive “flypaper” leaves or imprison them in snap-traps and underwater suction traps. They’ve detailed what the plants catch and how — plus something of the benefits and costs of their quirky lifestyle.

More recently, advances in molecular science have helped researchers understand key mechanisms underpinning the carnivorous lifestyle: how a flytrap snaps so fast, for instance, and how it morphs into an insect-juicing “stomach” and then into an “intestine” to absorb the remains of its prey. But the big question remained: How did evolution equip these dietary mavericks with the means to eat meat?

Fossils have provided almost no clues. There are very few, and fossils can’t show molecular details that might hint at an explanation, says biophysicist Rainer Hedrich of the University of Würzburg in Germany, who explores the origins of carnivory in the 2021 Annual Review of Plant Biology. Innovations in DNA sequencing technology now mean that researchers can tackle the question another way, searching for genes linked to carnivory, pinpointing when and where those genes are switched on, and tracing their origins.

There’s no evidence that carnivorous plants acquired any of their beastly habits by hijacking genes from their animal victims, says Hedrich, although genes do sometimes pass from one type of organism to another. Instead, a slew of recent findings points to the co-option and repurposing of existing genes that have age-old functions ubiquitous among flowering plants.

“Evolution is sneaky and flexible. It takes advantage of preexisting tools,” says Victor Albert, a plant-genome biologist at the University at Buffalo. “It’s simpler in evolution to repurpose something than make something new.”

Heritage Images | Getty