shaunl | Getty Images

David Cottrell got his $39,999 Tesla Model Y last February. The compact electric hatchback was a fantastic car, he says. But just a few months later, he decided to input the make and model into the website of an online used car retailer. Surprise! The Tesla was already worth $10,000 more than he and his wife had paid for it. They were thinking of buying a house in their hometown of Seattle, and the extra cash felt like a no-brainer. By June they had sold for $51,000—a tidy profit.

Now, Cottrell looks back at the transaction with a twinge of regret. He loves his new home and is excited about his reservation for a roomier Rivian electric truck, which is set to be delivered this summer. But when he plugged the same Model Y into the online used retailer again this month, he found the car would be worth only about $2,000 less than what he sold it for—even after factoring in the 20,000 miles he’s driven since then. “If we could have kept it, I could have driven for a year here and could have come out pretty equal,” he says.

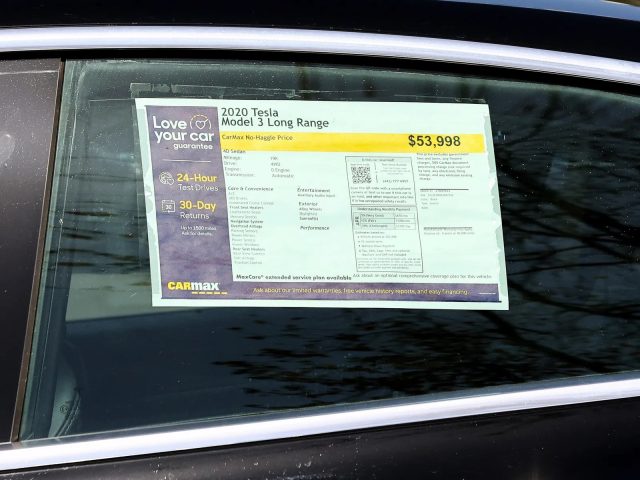

This is not the way a car’s life span is supposed to work. They’re supposed to lose their value over time. This is why used cars are, generally, less expensive than new ones. But right now, everything is topsy-turvy. A toxic mix of pandemic-era supply shortages and inflation have spiked prices of used cars and trucks, which were up 35 percent in March compared to the same time last year, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. It’s not unusual for certain used luxury cars, like Porsches and Corvettes, to go for more than their original sticker prices, says Luke Walch, the owner of Green Eyed Motors, a dealership outside Boulder, Colorado, that specializes in electric and hybrid vehicles. Now, “it’s trickled down into the commoner’s car,” he says.

Things have gotten extra strange in electric vehicle land, where used cars seem to be getting newer. Figures tracked by Recurrent, a company that follows the battery health of EVs, and the data firm Marketcheck suggest that last year, the majority of used electric cars for sale were four or five years old. Today, just under a third of used EVs are three years old. EVs sold in 2020 or 2021 make up 17.5 percent of inventory. “It is weird,” says Brian Moody, the executive editor of Autotrader, an online car marketplace. In fact, the whole situation is near-unprecedented, he says.

Mario Tama | Getty Images

If you’re someone who’s hoping to go electric right now, it’s also unfortunate. Despite the high prices, EVs and hybrids are moving out of lots faster than they can get them in, says Walch. Carvana, a company that buys and sells used cars online, says 90 percent of its electric vehicles are in the process of being purchased, compared to 45 percent just over a month ago.

The rise of the new used car started with the microchip shortage, which began to seriously affect car production in 2021. Today’s vehicles use at least 100 chips each to control their complex electronic systems, and electric vehicles, which are especially complicated, can use as many as 1,000. But when the COVID-19 pandemic first hit in 2020, automakers cut back on their sales forecasts and on their purchase of chips. Chipmakers sold their wares elsewhere. Then came federal stimulus checks, which sent thousands of dollars into US bank accounts. Some Americans sought big, chip-filled purchases, like computers, gaming consoles, and cars. But automakers no longer had the silicon to make cars happen and were forced to slow or even stop production. The mess pushed up the price of new cars and sent more cost-sensitive buyers into the used market, where prices soared, too.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine—and subsequent sanctions on Russian exports—led to new supply chain bottlenecks. The price of nickel, a component of some electric vehicle battery chemistries, swung wildly last month. And in the US, rocketing gasoline prices led car buyers to seek out electric vehicles. “Prices of [electric vehicles] were creeping up for a while, and then there was a big jump with the war and high gas prices,” says Al Bastanmehr, the owner of Green Light Auto Wholesale, which sells used EVs and hybrids in Daly City, California. “It’s just crazy. It’s at an all-time high.”

The new and used EV crunch—and the temptation for EV owners to flip their new Teslas, Ford Mustang Mach-Es, and even lower-end vehicles like Nissan Leafs—could stick around for a while. New cars are getting a bit cheaper, with new vehicle transaction prices falling by 0.3 percent between February and March, according to Kelley Blue Book, an automotive research company. But new vehicle transaction prices are holding steady—and even going up—for electric vehicles (which saw a 1.8 percent hop in that same time period) and hybrids (8.6 percent). In other words: New green cars aren’t getting any cheaper right now.

And here’s the big problem for electrics: Some new cars that were supposed to enter the market in 2020 and 2021 were never made. That means fewer used cars trickling down the market this year, and next year, and the next. “At some point the new car prices will recover, but it’s going to be a long time,” says Scott Case, the cofounder and CEO of Recurrent, the battery health company. “This whole system—it’s going to take a long time to work through and get to a new normal.”

This story originally appeared on wired.com.