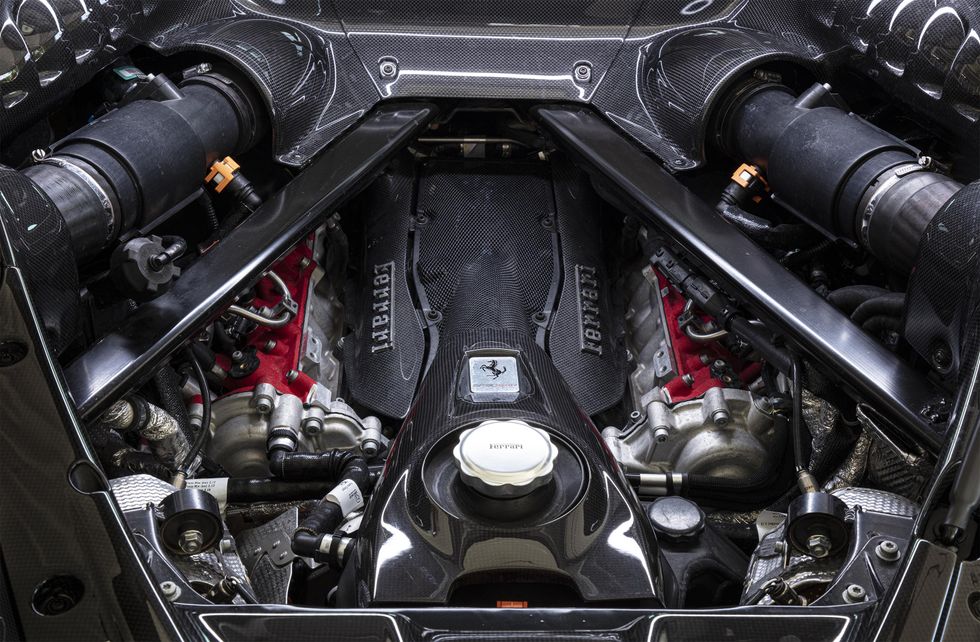

Yes, behind my helmeted head there’s a twin-turbocharged 4.0-liter V-8 shrieking, as technically advanced as any automobile engine ever. It generates a seismic 780 metric hp (or 574 kilowatts), sending it rearward to gummy Michelin Pilot Sport Cup2 tires. But that leaves two wheels and 220 hp unaccounted for. Which brings us to the Ferrari’s secret sauce: electricity.

The same sauce is cooking at every automaker that hopes to keep up in this record-smashing era of speed. The world’s leading sports- and luxury-car brands, together with muscle-car mavens like Dodge, are now pushing the envelope of the relatively inefficient internal combustion engine (ICE). Call it Peak ICE—the last hurrah of a technology that governments are ushering off the stage to combat climate change. But even now, years before EVs can finally put ICEs out of business, automakers are finding that electricity provides performance benefits that are too good to pass up.

Michael Leiters, who was Ferrari’s chief technology officer (he recently left the company), says there’s no denying that electrification in the car industry is largely being driven by the need to comply with strict emissions regulations, including for carbon dioxide. Yet Ferrari, and brands like it, are in a tricky position, having to always put speed and handling first. Customers who plunk down millions of dollars for classic Ferraris, or more than US $500,000 for the SF90 Stradale, wouldn’t have it any other way. “We firmly believe that everything we do in the electric field must be in line with our DNA, which for nigh on 75 years has meant obtaining performance with the shrewd use of technology,” Leiters says. “Our electric power trains are not there just to counter regulations but also to improve performance in a way which would not have been possible by using ICE power trains only.”

The twin-turbocharged 4.0-liter V-8 generates 780 metric horsepower; another 220 hp comes from the plug-in hybrid’s electric motors.Ferrari

As Ferrari’s first plug-in hybrid, the SF90 integrates a trio of electric motors. Spinning at up to 25,000 rpm, two permanent-magnet motors independently power the front wheels, or regenerate energy from braking to recharge the batteries. Wizardly digital controls, developed in Formula 1 racing, optimize traction and driver control, including the “torque vectoring” of individual front wheels to claw out of corners or stabilize the car under braking. A third axial-flux motor is sandwiched between the mid-mounted engine and the dual-clutch transmission. It fills in electric torque at low engine rpms or during gear changes that take as little as 200 milliseconds. Those motors are fed electrons by a 7.9-kilowatt-hour lithium-ion battery pack (with 84 pouch-style cells courtesy of SK Innovation) that’s laser-welded behind two racy sport seats. A powerful brake-by-wire system blends hydraulic and regenerative braking so smoothly that your foot won’t feel the difference.

The result is Ferrari’s fastest road car ever, peaking at 339 kilometers per hour (211 miles per hour). It’s also a joy to drive—exhilarating yet approachable, a car that your grandmother could learn to drive fast with a few lessons.

I take the Ferrari on a run down Fiorano’s straightaway, and it’s spooky quiet. Because the front wheels are driven independently, the car can travel 26 kilometers (16 miles) on electricity alone, at speeds up to 135 km/h (83 mph). That front-drive mode gets the car a green light in cities like London and Rome as they begin to bar polluting cars from their downtown areas. You switch the mode on by dialing it up on the Ferrari’s dramatic steering wheel, which integrates a cool arc of LED lights on its carbon-fiber rim to cue drivers to shift.

![]()

Drivers push a button on the steering wheel to choose one of four driving modes: all-electric drive (eD); hybrid (H); performance mode (represented by a checkered flag, selected); and qualifying mode (a clock).Ferrari

Select performance mode and the V-8 will fire up to recharge a depleted battery on the fly. Electric motors disconnect above 210 km/h, because there’s no need beyond that speed for inputs from the front wheels. Dial into qualifying mode and you unleash the Kraken, maximizing the full 162-kW electric capability.

Ferrari conservatively quotes a 2.5-second launch from 0 to 100 km/h (62 mph), and 0 to 200 km/h in 6.7 seconds. In a test by Car and Driver magazine, the car exploded to 60 mph in 2.0 seconds, breaking a seven-year-old record for production cars that had been set by the roughly $1 million Porsche 918 Spyder Hybrid. The SF90 also holds the lap record for production cars on the road course at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

On its home court, with de Simone at the wheel, the SF90 dominates Ferrari’s 488 Pista, with a ridiculous 2.5-second lap advantage over that ICE-only supercar. The SF90 also beat its previous record holder, the LaFerrari, by 0.7 second, a significant edge on this tight, 2.99-km circuit. That limited-edition LaFerrari cost more than $1 million new, and a used model recently sold for $3.1 million; by those cockeyed standards, the SF90 is a relative bargain.

Regulations aren’t the only thing putting heat on automakers, of course. From rocket-sled sedans like the Tesla Model S Plaid and Lucid Air to the Croatian-built Rimac Nevera hypercar, EVs are challenging everything we thought we knew about speed. The Rimac starts from $2.4 million, nearly five times the Ferrari’s price. But its four permanent-magnet motors deliver a loopy 1,408 kW (1,914 metric horsepower) and a claimed top speed of 412 km/h (256 mph). The Arizona-built Lucid Air that I recently tested amasses up to 1,126 metric hp. In its Dream Edition Performance trim, the Lucid can blast through a quarter mile in 9.9 seconds at 144 mph, not far off the Ferrari’s 9.6-second pace. Lucid’s spacious sedan can also travel an EV- record 837 km (520 miles) on a charge, 185 km more than Tesla’s best.

Eventually, people will want vehicles powered by internal combustion because they are quaint.

Automakers are finding it difficult to challenge those boldface numbers with internal combustion alone, especially as engines are relentlessly downsized to meet regulations. In recent times, turbocharging has played technological savior, sweeping the global industry, and squeezing massive power from even the tiniest three-, four- or six-cylinder engines. Ten- and 12-cylinder engines are on a virtual death watch, with V-12 purveyors like Lamborghini, Ferrari, Bentley, and BMW widely expected to eliminate these longtime markers of automotive prestige.

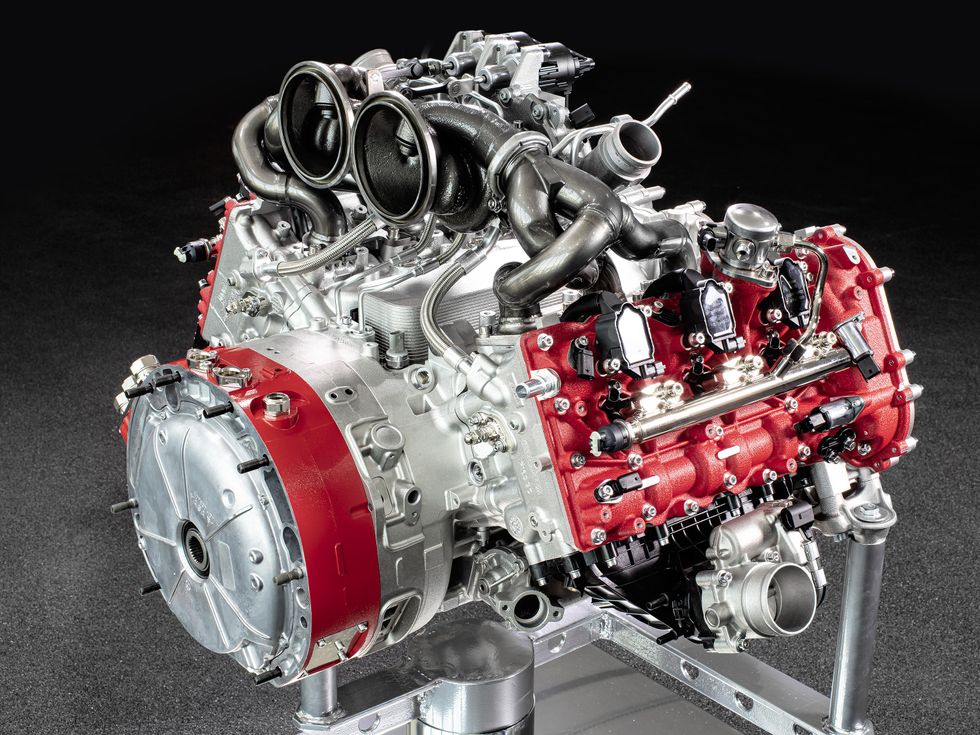

That makes the one-two punch of turbocharging and hybridization the only viable option to keep performance customers happy and their cars competitive. Porsche, McLaren, and Bentley are all developing hybrid models to bridge the gap, with the Porsche Taycan taking on Tesla on the full-electric front. A hybrid Chevrolet Corvette is expected to deliver about 662 kW (900 hp), even as its GM parent readies a 1,014-hp GMC Hummer EV. Lamborghini has been the stubborn holdout among speed merchants. But even Lamborghini recently relented, announcing plug-in hybrids throughout its model range by 2024, including a hybrid V-12 for its flagship Aventador, followed by its first all-electric sports car. At a private showing near the track, in a new building crammed with knee-wobbling historic racers, Ferrari gives us a glimpse of its near-term future: the 296 GTB plug-in hybrid, and a display of its magnificent new V-6 engine. The 296 GTB will become the first V-6 powered road car to wear a Ferrari badge. (The lovely Dino of the 1960s and 1970s, named for Enzo Ferrari’s late son, wasn’t officially a Ferrari.)

The upcoming Ferrari 296 GTB [top] has a transparent cover in the back to show off its V-6 engine [bottom]. Ferrari

The 296 GTB squeezes a shocking 663 hp from just 3.0 liters of displacement, for an industry-record 221 hp per liter. Now add 167 hp (122 kW) from an electric motor and a 7.5-kWh battery and you’ve got an unfair fight: The GTB’s total 830 hp gallops all over the 710 of the Ferrari F8 Tributo and its larger, twin-turbo V-8. Ferrari’s 812 Competizione, its traditional, front-engine V-12 flagship, makes the identical 818 horses but requires a 6.5-liter V-12 to do it—more than double the 296 GTB’s displacement. Is that a clock we hear ticking?

EV proponents may ask: Why not just skip this middle hybrid step and fully embrace the electric future? Some luxury brands, including Cadillac and Lotus, plan to do just that. But even as many automakers pledge to phase out ICE power trains between now and 2030 or 2035, some have been more circumspect. They surely see that EVs still make up fewer than 4 percent of new-car sales in the United States. For all the media clamor, it seems clear that many buyers are perfectly content with their ICE cars. That may go double for wealthy people who collect both new and classic cars like brightly colored candy. These people are used to getting what they want, and perhaps that includes garages filled with both EVs and ICE models.

As for pure performance, for all the hype over Tesla’s straight-line feats, its cars are still no match for the best of ICE, whether on a racetrack or winding road, or in the driver engagement and stimulation that separates performance buyers from their wallets. EVs have disadvantages that many fanboys simply refuse to acknowledge: heavy batteries, short ranges, and slow recharging.

For performance, mass is perhaps the biggest challenge. EVs still haul around battery packs that weigh hundreds of kilograms, whether they’re full of energy or tapped out. A Tesla Model S Plaid weighs 4,833 pounds (2,192 kilograms), compared with 4,000 pounds or less for a comparable midsize ICE sedan. Despite a modest edge due to low centers of gravity, that EV mass takes an unavoidable toll on top speed and handling, and it puts huge stresses on tires, brakes, suspensions, and cooling systems. A Formula 1 ICE car can still flick aside a Formula E racer like an underpowered, short-range toy.

The Tesla Model S Plaid claimed the track record for production EVs at the Nürburgring, the German circuit that’s the testing benchmark for one-upping automakers, with a lap of just under 7 minutes, 36 seconds. It can accelerate to 60 mph in about 2.0 seconds (Tesla claims 1.95, but only on a specially prepared, sticky drag-racing surface that’s moot for most drivers). That roughly equals the Ferrari’s performance. But when the road begins to curve, Tesla’s electric porker is left for dead by a long list of more-agile, better-braking ICE models—including cars from Ferrari, Porsche, and Lamborghini that can run the ‘Ring in 7 minutes or much less. The Tesla also requires several minutes of battery and systems prep to perform a single automated launch; the Ferrari’s drag runs are easy and repeatable. Even for the Ferrari, its full monty of electric, qualifying-mode torque lasts only about seven laps at Fiorano. Coincidentally or not, that’s nearly the exact length of a lap at the Nürburgring.

The superfast SF90 plug-in hybrid is a pioneering step from Ferrari and an augury of what’s to come in performance cars. Ferrari

Ferrari, for its part, refuses to sacrifice its fabled handling and sensations on the electric altar. Including its 72-kg Li-ion battery, the Ferrari’s hybrid hardware adds just 275 kg, a gain that’s more than made up for via improved power and traction. Total curb weight remains a slender 1,570 kg. A jaw-dropping weight-to-power ratio of 1.57 kg/hp tips the scale in Ferrari’s favor: It’s a new record for any volume-production supercar.

Seeking every edge, my SF90 trimmed another 30 kg via its optional $56,240 Assetto Fiorano package, which includes titanium springs and titanium/Inconel exhaust system, carbon-fiber door panels, and underbody and racing-derived Multimatic shock absorbers. And don’t forget sound. EV proponents may scoff, preferring the blissful near silence of electric motors. But there’s a reason EV makers are pumping digitized engine sounds through their audio systems, even if it’s more a Star Trek whoosh than a literal translation of a stonking V-8. To many enthusiasts, those soundtracks—heavy metal, for a Detroit V-8, or a hollow rasp, for a Porsche inline six—are a key reason for their purchase. The Ferrari hybrid, for its part, still wails like a La Scala tenor to an emotional, 8,000-rpm peak.

Those Tesla-thrashing ICE sedans include Cadillac’s new CT5-V Blackwing, which is basically a street-legal race car that combines a 685-hp, supercharged V-8, a 202-mph top speed, and endorphin-rushing handling. I drove that $84,940 CT5-V at the Virginia International Raceway for hour after hour on a scorching summer day, where its all-day stamina and capability were thrown into stark relief.

“It’s going to be a long time before you can do what we did at VIR with a battery electric vehicle,” says Tony Roma, the CT5-V’s chief engineer. “Gasoline is just a fantastic storage device for energy. That’s not a political statement, just physics. But the tech is changing so fast that 10 years from now we’ll have a completely different discussion.”

Indeed, Cadillac says the Blackwings will be its final gasoline-powered, V-badged performance models. Roma and his team are busily developing EVs, including the Lyric SUV and Celestiq sedan.

Why not just skip this middle hybrid step and fully embrace the electric future? Some luxury brands, including Cadillac and Lotus, plan to do just that.

While dual-power-train hybrid tech may be fine for Ferraris and other cost-is-no-object brands, Cadillac intends to jump straight from ICE to electricity. “By the time costs come down enough to make a great, affordable ICE-hybrid performance car, we’ll be able to make you a full-electric car that you’re going to love,” Roma says.

Most improbably, perhaps, Dodge—creator of the notorious Demon, whose drag-race times challenged Bugatti’s million-dollar models—intends to design an electric muscle car that will be even faster.

“Our engineers are reaching the practical limit of what we can squeeze from an internal combustion engine,” Dodge-brand boss Tim Kuniskis says. “We know that electric motors can give us more.”

Derek Jenkins, Lucid’s chief designer, naturally agrees, even as he acknowledges the current limitations. “You’re dead on about the weight factor; that’s a huge disadvantage, today,” he says, while allowing that EV technology will finally overcome all disadvantages.

And where costs are plummeting for EVs, they’re already rising for ICE cars, as automakers divert resources elsewhere. Soon enough, automakers will refuse to pour money into ICE development just to win the arms race.

“You have these corner use cases, but even for lap times, EVs will give access to new levels of power, and the ability to put down that power,” Jenkins says. “If you want, say, 1,500 horsepower and torque vectoring in an ICE car, that’s going to be tough to do, and very expensive.”

Eventually, he says, people will want vehicles powered by internal combustion because they are quaint. “It will be purely nostalgia-driven, with nothing to do with value or performance.”

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web