Within the profession, it’s a fact of life, according to Eleanor Blair, author of the 2018 book, “By the Light of the Silvery Moon: Teacher Moonlighting and the Dark Side of Teachers’ Work,” and a professor at Western Carolina University.

“Teacher moonlighting is like some dirty little secret that we all know about, we talk about, teachers share ideas about, but nobody wants to put it on the table—that we work at Steak ‘n’ Shake or these other places,” said Blair, a former public school teacher who used to moonlight as a waitress.

Data is imperfect and sometimes lags a few years behind, but various credible estimates—from the federal government’s National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) to the National Education Association (NEA), the largest teachers’ union in the country—find that a significant percentage of U.S. public school teachers work at least one other job to supplement their income. For new teachers, that income averages just over $41,000, according to data from the 2019-20 school year collected by the NEA, while the average teacher salary across all levels of education and years of experience is about $64,000.

The most recent data made public by the NCES, drawing on surveys conducted in the 2017-18 school year, found that 18 percent—or about 600,000—public school teachers in the U.S. held second jobs outside the school system during the school year, making teachers about three times as likely as all U.S. workers to juggle multiple jobs at once.

Other measures that account for second jobs both outside and within the school system have found the arrangement to be considerably more prevalent. NEA Research conducted a survey of more than 1,300 public school teachers in late 2020, asking them about the jobs they held in 2019, and found that 41 percent of preK-12 teachers worked more than one job. The NEA survey also breaks down what kind of second jobs teachers have. (These survey findings are being released publicly here for the first time with permission from NEA.)

Of the teachers who said they work at least one other job, 17 percent reported working their second job on weekdays in the early mornings before school, 62 percent said they worked weekdays after school hours, and 48 percent said they put in their hours on weekends during the school year.

“It’s really kind of disheartening when you think that many teachers not only have bachelor’s degrees but master’s degrees and still have to hustle for their income. It sends a message,” said Donna M. Davis, an education historian and professor at the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

She added: “The system is clearly broken when we have highly qualified professionals needing to supplement their income to survive, who are one catastrophe—one paycheck—away from complete ruin.”

In a national survey of nearly 1,200 classroom teachers conducted in spring 2021 by the Teacher Salary Project, a nonpartisan organization, 82 percent of respondents said they either currently or previously had taken on multiple jobs to make ends meet. Of them, 53 percent said they were currently working multiple jobs, including 17 percent who held jobs unrelated to teaching.

In a free-response portion of the Teacher Salary Project’s survey, hundreds of teachers called out the field for failing them, describing again and again the “humiliating” experiences they endure to stay in a profession that the public purports to value.

“It’s embarrassing, as a college-educated professional, to be offered friends’ basements as a place to stay so that I don’t end up homeless for a bit,” wrote one teacher in Colorado.

“There have been months when I had to choose between a doctor’s or dentist’s appointment for myself,” wrote another teacher, who lives in North Carolina. “I’m so far from living the dream.”

Another said: “It can be a struggle deciding what bill to pay and what bill to skip so we can eat.”

Perhaps most jarring of all was the teacher in California who said that, in order to support her family financially, she has become a surrogate mother. Twice. “I’m literally renting out my uterus to make ends meet,” she wrote.

As the data suggests, nearly half of teachers’ second jobs are education-adjacent, such as tutoring, nannying and coaching. But the majority hold jobs outside of education. Think: restaurant servers, bartenders, Lyft and Uber drivers, food couriers for DoorDash, grocery shoppers for Instacart, real estate agents, cosmetics sales representatives and retail associates.

“It’s important to distinguish between jobs that people are doing because it’s something that they’re excited about … versus someone who’s taking on that additional work because it’s the only way they can make ends meet,” said former Education Secretary John B. King, now a candidate for governor in Maryland. “And unfortunately, because teacher pay isn’t what it should be, many folks are in that latter category.”

In interviews, economists and historians described how second jobs that align with education—say, an art teacher who sells artwork to clients outside of school—are more palatable than second jobs outside of the field entirely.

“For somebody whose side gig is playing in the local symphony, people could say, ‘Yeah, it’s great to have a real musician teaching the kids music,’” explained Dick Startz, a professor of economics at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “But someone who is shopping for Instacart? We’re glad someone does it, but a teacher is not who we expect that person to be.”

When teachers’ outside work is career-related, even if it’s not optional, it can at least be enriching and fulfilling, argued Paul Fitchett, an assistant dean and professor at the University of North Carolina in Charlotte who previously worked as a public school teacher. “I don’t think that all moonlighting is bad, especially if it’s in your job sector,” said Fitchett, who used to do financial administration for a temp agency during the summers.

A few of the teachers interviewed for this story argued that their work outside the classroom was refreshing and gave them opportunities to socialize with other adults. But on the whole, teachers who have to work in unrelated roles to earn their extra income found it demoralizing.

“I’ve done DoorDash. I’ve done Shipt grocery delivery. But every time I do that, it feels disheartening,” said Ashley Delaney, a high school art teacher in Paterson, New Jersey, who has been in the classroom for two years. “I went to school for teaching, but I can’t afford to pay my bills unless I deliver people’s fast food?”

Now, trying to keep her side hustles in the realm of education, she tutors after school, babysits and occasionally accepts commissions for pet portraits. She is an art teacher, after all.

This trend of teachers working multiple jobs is hardly new. But pandemic-related stressors and the pressure of rising inflation, which forces them to stretch each dollar ever further, have propelled teachers to re-evaluate the cost-benefit calculations they’d accepted long ago and to reimagine how the rest of their careers might look. Some are plotting to leave the field, hoping to roll their side hustle into a full-time job; others have already left. The majority interviewed for this story, though, still love teaching and don’t want to leave it if they don’t have to. But to stay, something will have to change, they said. They can’t keep working extra jobs to subsidize their insufficient salaries.

“It’s sad, because I thought I’d spend my life being a teacher. I love teaching,” said Reaghan Murphy, a special education teacher outside of Chicago who bartends and nannies on weeknights and weekends. “This is what I want to do, but it’s just not sustainable.”

That’s the problem with teachers who moonlight, said Blair, the author of one of the only books on the topic. The ones who care enough about the kids, who believe in the transformative power of teaching, are the ones who stay. And in order to afford to continue being a teacher, they have to run themselves ragged working multiple jobs. Why, she asked, is this country doing so little to keep them in their jobs?

“If somebody wants to do the job, we need to find ways to support them and help them be successful,” she said emphatically. “Selling cosmetics or driving an Uber is not helping them to be a teacher.”

But while Blair and others have ideas for building pathways for career development, progress nationally has stalled. For years, actually.

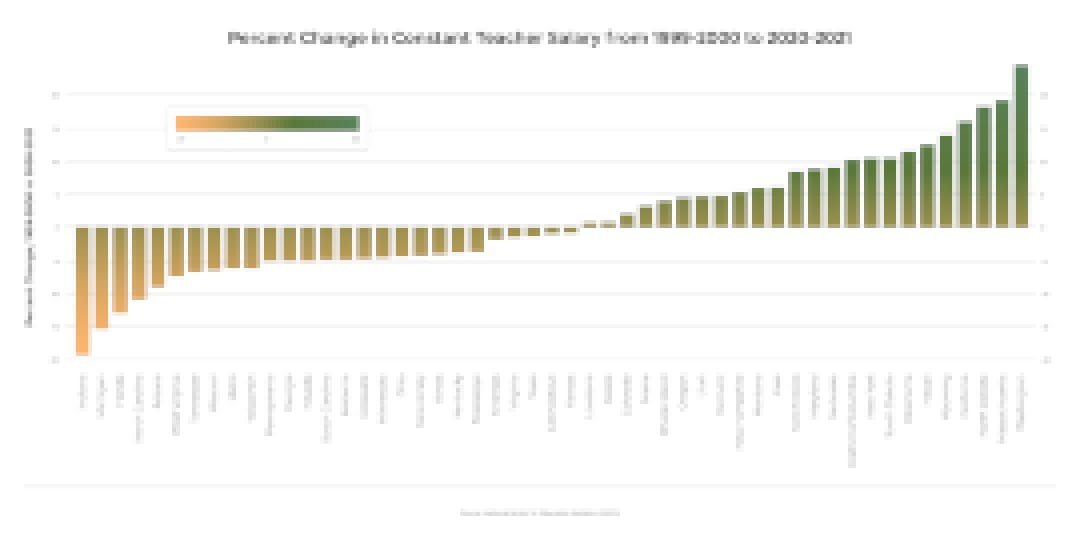

Though teachers across the U.S. have received modest pay increases over the past two decades, these raises have not been enough to keep pace with inflation in many places. As a result, teachers’ actual earnings between the years 1999-2000 and 2020-21 stagnated in two states, and in 27 states, they declined.

The worst offender of all is Rothrock’s Hoosier state, where, adjusted for inflation, average teacher pay has declined by almost 20 percent since 1999-2000, about a year before Rothrock landed her first teaching position.

On paper, Rothrock makes about $60,000 per year now, more than double her starting salary of $29,000. But adjusted for inflation, her starting salary in January 2001 would have the buying power of $47,000 today. This means her salary, in real dollars, has increased by only $13,000 in 21 years.

The pervasiveness with which teachers work second jobs remains, at best, invisible and, at worst, permissible to the general public.

Look at popular culture, which perpetuates the normalization of the teacher side hustle. In the pilot episode of the hit television series “Breaking Bad,” protagonist Walter White, a high school chemistry teacher, is shown working after school at a car wash. His students mock him for it. Later, White turns to making and selling methamphetamines to cover his medical bills and secure his family’s financial future. In the teen comedy film “Mean Girls,” Sharon Norbury, the high school calculus teacher played by Tina Fey, bartends a couple of nights a week at a restaurant in the mall. Both White and Norbury are made to feel degraded by their part-time jobs. But as a viewer, while there’s the shock factor of White’s side job as a drug trafficker, the fact that these teachers would have a side job at all is presented as quotidian.

Among the public, misconceptions about the teaching profession abound, leading many to view teachers’ side hustles as innocuous. The assumption is that teaching is easy work, with short days ending at 3 p.m. and summers off, making the season well-suited for earning extra wages.

Of the 30 teachers I interviewed, whose annual salaries range from $32,000 to $98,000, every single one disputed that idea. So did King, the Education Secretary during the Obama administration and a former classroom teacher.

“Some of the things people miss is all the time that teachers spend … preparing for class, planning for class, all the time that teachers spend grading and looking at student work, and giving students and families feedback on student learning,” King explained.

Most people, he added, also overlook the benefits that are built into many professional roles but not available to teachers, such as the flexibility to schedule a doctor appointment on a Thursday morning or to excuse yourself to the restroom without any planning or strategizing. “That level of intensity is, I think, different from a lot of other work settings,” King said.

“We ask a tremendous amount of teachers,” he added. “We also ask them to hold the emotional weight of all the things their students are going through. And so I think we need to make sure that the compensation and esteem for the profession reflects the extraordinary work people are doing every day.”

Even before the pandemic, but especially now, teachers are expected to be not only instructors, facilitators and subject matter experts, but mentors, family liaisons, behavioral interventionists and whatever else the crisis du jour demands. With staff shortages ballooning into an all-out crisis of its own in recent months, many teachers’ planning periods have disappeared, as they fill in for absent colleagues down the hall, forcing lesson prep, grading, emails and other ancillary work into the evenings and weekends. For teachers who pick up shifts after traditional school hours, or turn on apps like Lyft and DoorDash to earn some fast cash, the pressure of figuring out when and how to get it all done—to pay the bills, to be an effective teacher, and do it all with a positive attitude—has snowballed into a scenario that no longer feels tenable.

The balancing act takes a toll not only on teachers’ mental health but also on the quality of instruction they are providing in the classroom.

Marcus Blankenship, a sixth grade history teacher in Asheville, North Carolina, who drives for Lyft a few times a week after school and on weekends, described the intense fatigue that sets in after eight hours of being “on” with his 11-year-old students and another four or five hours of being “on” with his passengers, many of whom are tourists eager for a full list of local recommendations or a regional history lesson.

Fitchett, the professor at the University of North Carolina in Charlotte who doesn’t view moonlighting as troublesome in all cases, said, “It’s the during-the-year work when you’re teaching from 7:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. then jumping in an Uber from 4:30 to 11 p.m.” that’s the problem. That rings true for Blankenship.

“It’s mentally exhausting by the end. What I need to do when I get home, at that point, is either grade papers or write lesson plans. But I just don’t have it. I don’t have it left in me,” Blankenship explained. “I can’t be the best teacher that I want to be and do everything I need to do in order to live.”

Monet Gooch, a special education science teacher in Prince George’s County, Maryland, gets surprised reactions from all sides about her outside jobs tutoring, modeling and doing event security for concerts and professional sports games in the Washington, D.C. area.

Her eighth graders have asked her why she’s late to school. They can’t believe it when she explains that she has a long commute and works other jobs after teaching.

“One of my students was, like, ‘You have got to slow down. Why do you work so much?’” Gooch recalled. “And I was like, ‘Well, teaching doesn’t pay enough. I gotta pay my bills.’”

Gooch’s coworkers at the event security gig—where a handful of other teachers from her school also work—are floored to find out that she is a public school teacher.

“Somebody will ask, like, what do I do during the day?” she explained. “I tell them that I’m a full-time teacher and they’ll ask, ‘How are you doing this and teaching?!’”

To that she replies with the same answer she gives her students: She has to pay the bills.

A number of factors contribute to how far a teacher’s salary goes—family structure, caregiving responsibilities, health issues and student loans among them. While many teachers in the U.S. must work second jobs to live comfortably, plenty do not.

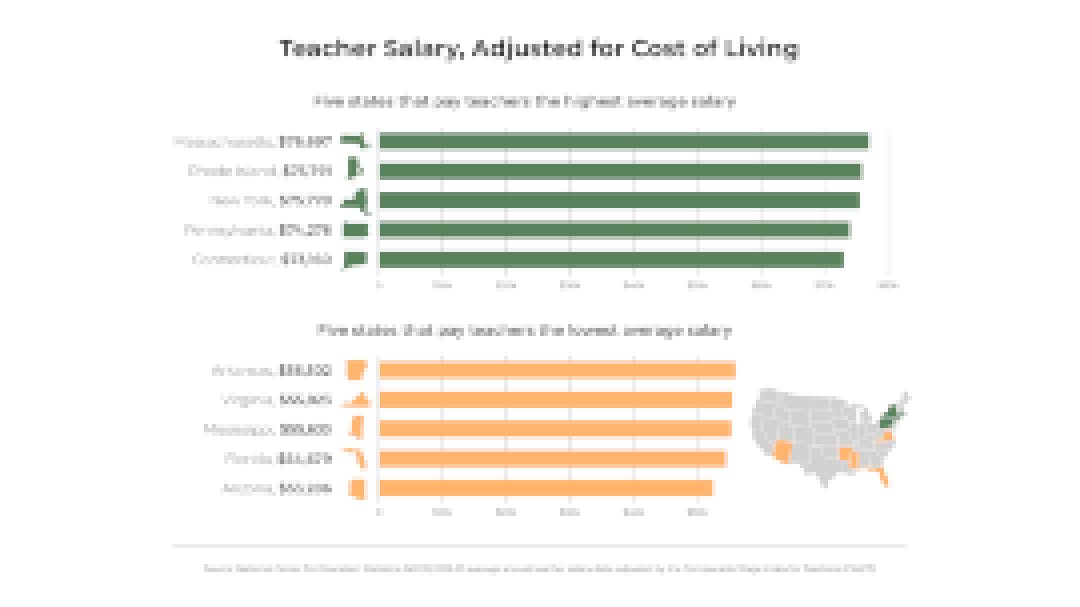

Some of them live in states that pay better than others. An EdSurge analysis of 2019-20 teacher salary data, adjusted for cost of living, found the five states that pay teachers the highest are Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New York, Pennsylvania and Connecticut. Rothrock’s state of Indiana, along with the Carolinas, falls in the bottom 20.

But it’s not just about geography. Others have partners or family members who support them. Dozens of teachers who filled out the Teacher Salary Project’s survey last year noted that, if not for their spouse’s income—which was in some cases several times greater than their own salary—they would be working additional jobs.

“It is very stressful and difficult to stay motivated and feel respected as a professional when you know you wouldn’t be able to support your family on your income,” a teacher in Colorado wrote. “If it wasn’t for my husband’s job, I wouldn’t be able to afford housing in my area and provide for my kids.”

Every teacher I interviewed had their own reasons for taking on a second job. Some were single or divorced and had to carry their rent or mortgage payments with their sole income. Others were single parents or caregivers, responsible for covering the expenses of others, or had family medical issues that siphoned away much of their monthly take-home pay. Many were married to other educators or had a partner with a similarly modest income, and a number of them had onerous amounts of student loan debt to pay down each month.

Delaney, the art teacher and tutor in New Jersey, was one of many single teachers who pointed out an assumption in the profession that educators just have to get by on their salaries for the first few years, until they find a partner who can support them financially.

“That’s not always the case,” she said, noting that she recently decided to live without a roommate for the first time and that it has caused tremendous financial stress. “Grown adult teachers shouldn’t have to rely on a partner to live by themselves.”

For educators whose lives didn’t follow their planned trajectory, there is little to no margin for error. Any disruption or deviation from what’s “normal”—going through a divorce, having a child with a disability, being unmarried in their mid-30s—can be financially devastating on a teacher’s salary.