Moms and dads stormed into the Spotsylvania county town hall, in Virginia, in early November, hell-bent on purging all “objectionable” books from the scholastic jurisdiction. Novels containing any commentary about race, sexuality and sexual content were put under the microscope, as a fresh reactionary panic takes aim at the stacks in high school libraries. “Results for gay, 172. Results for heterosexual, two,” said Christina Burris, one of the attending parents, who used the district’s literature search function to make her point. The board relented, voting 6-0 to enact a liquidation.

One of the books targeted by name was 33 Snowfish, an acclaimed 2003 novel concerning a trio of runaway teens and all sorts of sordid, Kids-ish behavior. The concerned parents of northern Virginia believed that heady themes of poverty, addiction and abuse have no place in the sanctums of learning, and therefore, the book needed to go.

When Paul Cymrot heard about the meeting, he tracked down as many copies of 33 Snowfish as he could find. He soon discovered, ironically, that book was never really in the school library. 33 Snowfish is barely in print, and Cymrot tells me that it was an ebook version, lingering in some dusty corner of the school library servers, which sparked the initial animus.

The moral militancy immediately backfired, because Cymrot knows a good business opportunity when he sees one. He’s owned the Spotsylvania-area Riverby Books for 25 years, and possesses a shrewd nose for the ebbs and flows of the publishing market. One bookselling truth remains eternally undefeated, explains Cymrot. When a censorious zeitgeist swallows up a novel, a lot of people will want to buy it.

“It was not easy to find a box full of 33 Snowfish, but we did,” he continues. “We sold all that we bought, and we kept a couple as loaners because we wanted to make sure any students in the community could see what the fuss was about. There will always be some around.”

It’s now easier than ever to read 33 Snowfish in Spotsylvania county, subverting the rightwing siege on the supposed woke conspiracy infecting school libraries.

New ominous headlines about book bannings trickle in all the time. Just this month, Texas state representative Matt Krause pushed for the ousting of 850 books, including classics by Alan Moore and Margaret Atwood, from the public curriculum. A few days earlier, Parents in Kansas City stormed school conventions because they fear that their children might start internalizing the wisdom of Alison Bechdel or Angie Thomas. Two members of the board at the Spotsylvania meeting floated the idea of literally burning the offending titles, which would be an assault on both our precious norms and our precious subtext.

As always, the impetus of the mania is simple, stupid and cynical. The Republican party has made a concerted effort to bring outré philosophic principles like critical race theory to the heart of our politics, which is why the Virginia governor-elect, Glenn Youngkin, spent much of his time on the campaign trail griping about Toni Morrison’s Beloved. Parents took the bait, and overnight high school librarians – those brazen extremists pushing their anti-American agendas by cataloging Pulitzer winners from 1987 – were put in the crosshairs.

These books are rarely inflammatory or obscene; instead, they simply contain narratives about race, gender and inequality that chafe against prescribed American ideology. That’s more than enough for an emboldened conservative movement.

But there is no evidence that the wave of book bans are actually accomplishing their intended ambition. If anything they’ve achieved the opposite effect. Sales of Beloved increased after Youngkin transformed Morrison into a partisan figure, and Jerry Craft, an author and artist who found himself on the Krause list for his 2019 graphic novel New Kid, has spoken at length about how legislative suppression is an unlikely boon for his career. “What has happened is so many places have sold so many copies because now people want to see what all the hubbub is,” he said, in an interview with the Houston Chronicle. “They’re almost disappointed because there’s no big thing that they were looking for.”

In 2021, with countless different merchants all manacled together by an intercontinental supply chain, proscribing a novel is almost entirely ceremonial – more of a whinging fit than a genuine political project. The Nazis burned thousands of books after seizing Berlin in 1933. Today, if a constable comes looking to repossess your literature, a replacement copy can be delivered to your mailbox the next morning.

In fact, the booksellers I spoke to for this story all seemed eager to take on the government’s injunction as a spiritual challenge – almost like a test of their moral fortitude. Mark Haber, operations manager at Houston’s Brazos Bookstore, tells me his staff put up a display featuring a selection of the books evaporating from Texas school libraries. (Beloved and Michelle Zauner’s Crying in H-Mart are performing very well.) “We had a drive where people could buy a banned book as a donation for a free library somewhere in the city,” says Haber. “The bannings feel so organized. They aren’t targeting a specific book, they’re targeting ‘books’ in general.”

Brazos, of course, is part of Houston’s liberal enclave. There is a self-selection bias in his sales figures and customer clientele, which Haber happily admits. “It’s definitely a political stance,” he says. “We have customers who’ve maybe already read the book, and just want to buy it again.”

In fact, Cymrot tells me that he thinks that the book-ban sales bump is truly a bipartisan phenomenon. He notices a surge regardless of what party is relitigating the library. Earlier this year, when six of Dr. Seuss’ books left circulation due to some offensive caricatures in the pages, Riverby thrived once again. “These paperbacks in our basement suddenly became collectibles,” he says.

At the very least, the censorship campaigns may encourage kids to read more. I like the idea of enterprising teens wielding the Krause agenda like a summer reading list, checking off every title, one by one, until they’ve firmly opened their third eye.

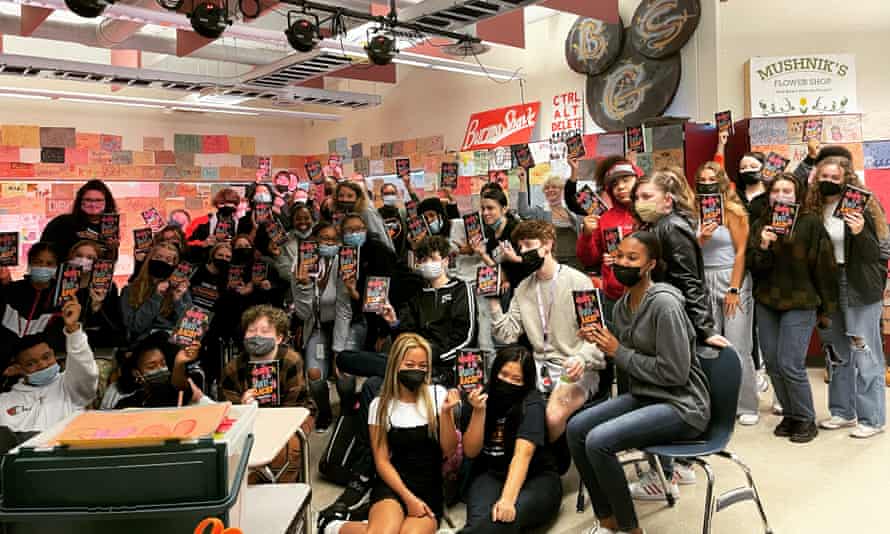

One of the most heartening stories that surfaced from the hysteria occurred in York county, Pennsylvania, where local ordinances forbade teachers from using a swath of texts in their lesson plans last November. (The taxonomy was bizarre. Biographies of Aretha Franklin, Malala Yousafzai and Eleanor Roosevelt were put on ice.) High schoolers around the community roused to action – staging campus protests, canvassing the local papers and eventually winning a reversal of the policy in September.

Today, the confluence of students and teachers who overturned the ban are known as the Panthers Anti-Racist Union, named after the mascot of Central York high school. The group aims to continue their social justice advocacy into the future, which could soon result in much bolder action than the mealy proclivities of the local school board.

“We’ve always said this organization is about creating a safe space for everyone to talk about who they are, and what their struggles are. Not just in our school community, but in their lives,” says Edha Gupta, a senior at Central York high school and a member of the Panthers Anti-Racist Union. “Any healthy way for people to genuinely express how they’re feeling about these matters. We want a place for students to feel like they have the authority to speak up about what they’re passionate about.”

“I went through the list of the banned books and I thought they sounded great. My mom had a ton of them, I got others from random people,” says Olivia Pituch, another member of the union. “It’s funny, the ban made me more curious to see what they were about.”