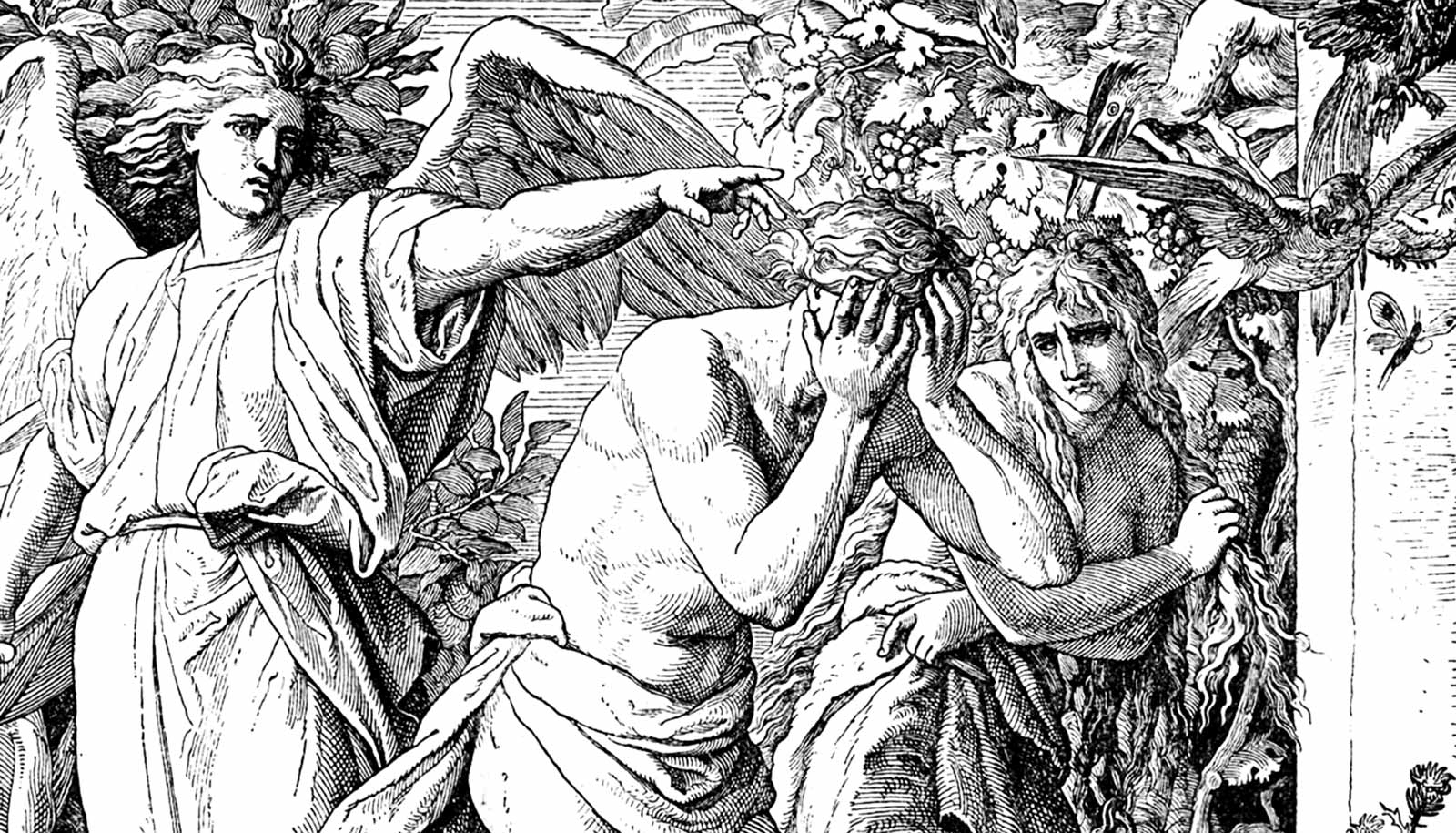

Shame is one of the first emotions mentioned in the Bible. In the Garden of Eden, Adam and Eve never felt it even though they were naked. But what precisely did that mean?

But after the Fall, shame becomes constant and unavoidable. It’s experienced hundreds of times by major and minor biblical characters and sometimes collectively by entire peoples. God metes it out as punishment to the worst sinners. It’s a fate almost as bad as death.

In a recent article in the Journal of Ancient Judaism, Anthony Lipscomb, a PhD candidate in Near Eastern and Judaic studies at Brandeis University, argues that the ancient Hebrews didn’t think about shame the same way we do.

“Shame is somehow parallel, somehow in a relationship with the idea of death.”

For us, shame is an internal emotional state. You can feel it without displaying any outward physical signs. But a clear separation between mind and body is a Western idea that developed in ancient Greece.

In the Hebrew Bible, which was written between 1200 and 100 BCE, there was no clear division between the psychological and physical. “The Israelites didn’t have a concept of the internal self like we do,” Lipscomb says.

Instead, emotions manifested themselves in physical activity or an outward sign on the body. Feelings weren’t an immaterial experience hidden within one’s inner depths. They displayed themselves publicly and changed your relationships with the people around you.

“When you say, for example, ‘I’m happy, I feel good,’ it’s not referring to an inner state of contentment,” Lipscomb says. “It happens in a social context like rejoicing with others and involves a physical activity like worshiping or giving thanks to God.”

Take the story of Tamar, daughter of King David, who is raped by Amnon, her half-brother. Pleading with Amnon not to violate her, she says, “Where will I carry my shame?”

Lipscomb says she means this literally. Her disgrace is not an internal feeling but an actual physical burden she will be forced to carry.

And we see how the burden is manifested after Amnon rapes Tamar. She throws dust on her head and rips her tunic.

“These are the signs of the burden she’s carrying,” Lipscomb says. “Her shame isn’t an inner trauma, though certainly sexual violence traumatizes, but rather it is a public enactment of Amnon’s violence and her diminished standing in the community.”

In his article, Lipscomb looks at shame in the book of Job. Job’s friend, Bildad, tries to convince him of God’s righteousness. He assures Job that God deals with good people justly. Those who hate the good, he says, “wear shame.”

Shortly before Bildad’s speech, Job says his anguish is so intense it’s as if “my flesh is clothed with maggots.” Job is still very much alive, but he feels as if he’s already a corpse rotting in the ground.

Lipscomb argues there’s a link between wearing shame and being clothed with maggots. In the Hebrew imagination, shame was a state of physical suffering on a continuum with death. It led to a degradation of the body akin to how a body decomposes after burial.

“Shame is somehow parallel, somehow in a relationship with the idea of death,” Lipscomb says. “And what takes place, what happens when you die? Well, you have this physical bodily diminishment.”

The same connection with death occurs in Psalm 89 when, wondering why God appears to have broken his covenant with King David, the author laments, “You [God] have cut short the days of his youth/You have wrapped shame around him!”

The shame endured by David—and by extension, his followers, the Israelites—literally ages them. It weakens and wears down the body, taking years off their life and hastening their progress toward death.

Restoring the Bible’s original meaning in this way can start to make it seem irrelevant to a contemporary audience. But Lipscomb argues this need not be the case.

For the ancient Hebrews, shame couldn’t be hidden. It represents a defeated or degraded state visible to those around you and elicits a response from others.

If you brought shame upon yourself by doing something wrong, you had to act publicly to make amends to the community. If you brought shame on someone else for no good reason, the consequences of what you did would be visible.

But if shame is a private affair, as it is in modern society, you can hide what you did wrong. The person who is wronged can suffer in silence or out of sight. Emotions can be divorced from their public and societal morality.

“The West’s deeply entrenched practice of considering emotions private renders devotion to God a matter of inward piety,” Lipscomb says. “This could lure one into thinking that being square with God is purely a matter of the heart without the need to take action.”

The biblical tradition suggests something else, Lipscomb says: “What we do matters as much as what we feel.”

Source: Brandeis University