Cambridge University lecturers are accusing the institution of pressuring them into taking on “explosive workloads” to deliver its famous one-on-one tutorials.

A survey of university teaching officers (UTOs) by the University and College Union branch found that a third (35%) felt they could not refuse requests from peers and superiors to take on extra weekly tutorials, or “supervisions” as they are known, even though nearly half of those surveyed said they would like to deliver fewer of them.

Michael Abberton, the president of the UCU Cambridge branch, said: “The supervision system is not working for anyone in its current set up. It exploits casual workers, who need to earn an income and accumulate teaching experience. It overburdens permanent staff, who are already under the pressure of explosive workloads.

“The university and the colleges cannot keep on denying that the system needs urgent reform, with improvements over pay, contracts and training for undergraduate supervisors.”

A Cambridge University spokesperson said the system granted supervisors flexibility to choose which and how many colleges they work with and their hours, while training was provided for free and average pay is “well above the living wage”.

He added that “since the colleges are separate legal and financial employers, they cannot be covered by a single agreement”.

Nearly three-quarters (73%) of the UTOs surveyed by UCU said they delivered more than five hours of supervision a week, with preparation time averaging about 20 hours, on top of their full-time teaching schedules. Half said they worked more than 50 hours and 21% exceeded 60 hours a week, with some saying they were prevented from doing the research required to further their academic careers.

One humanities UTO who spoke to the Guardian said she had been pressured by peers who warned the courses would not remain viable, and “to stay in the good graces of one’s senior colleagues”, especially given an “unstated expectation” that junior colleagues would supervise more, leaving her with only three weeks to spend on research.

Fifty-six per cent of respondents also complained about low rates of pay, at £31 an hour of supervision, which does not cover preparation. The union estimates that in some cases this amounts to an hourly rate of around or below minimum wage.

The survey builds on research from last year, which found that although Cambridge advertises supervisions to prospective students as a core feature of its world-leading teaching model, many of these are delivered on a “gig economy” basis. Nearly a third (28%) are delivered by teaching officers, who have a secure contract with the university, while almost half (45%) are delivered by precariously employed staff.

This month, staff across UK campuses began 10 days of strike action over pay, pensions, insecure contracts and deteriorating working conditions.

Supervisors also said the “byzantine” nature of the university’s structure – in which the central university arranges supervisions for some subjects and year groupings, and individual colleges for others – was partly to blame for the lack of transparency over differing rates of pay they received.

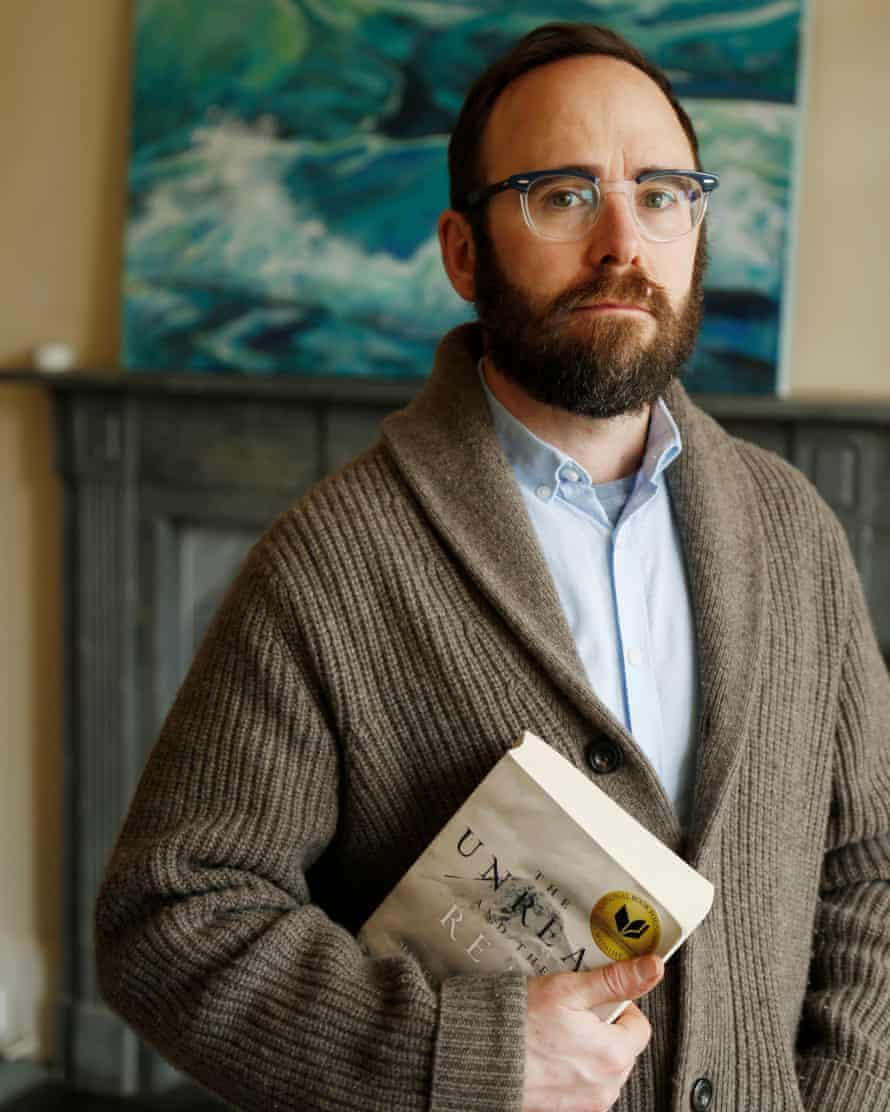

“There’s nothing rational about Cambridge, it’s a product of history and changing government regulation and different forms of influence. There’s no way to understand except by being in the institution and having to navigate it,” said Graham Denyer Willis, a UTO who said “extreme amounts” of supervision had taken a toll on his career.