Teenager Ellis is inspired by a surreal vision that may be a glimpse into parallel worlds or a hint of madness; by Harrison Kim.

Kids pretend; but I didn’t stop. At 15, I faked being a drug addict. I copied the stoned behaviors I’d seen in the anti-drug movies the principal showed in the school gym. I liked the low-talking way of the high-on-hashish, and the childlike sound of their laughter. I didn’t want to smoke. Those movies scared me, and I knew something bad would happen if I inhaled. Everyone else would be okay, but I knew I was different.

I acted slowed-down, in school or when dealing with kids I didn’t like, which was most of them. My parents asked, “Are you on drugs?” and I told them, “No,” but the more I said “no” the more they asked the question; and then it changed to, “Ellis, we think you’re on drugs, don’t lie to us.”

My parents were practical people.

“Ellis, could you come help me tie some fishing flies?” asked my dad.

“I’m not into fishing,” I said.

“A boy not into fishing?” asked Dad. “How can that be?”

I knew if I helped him, I’d have to interact and smile and attempt to learn a technical skill I wasn’t interested in. With Dad, I wanted to be real.

I worked Saturdays for Mr. Tosk, the farmer next door.

“You’re always on time,” he said.

“I like working here,” I told him.

That was an exaggeration. I mostly hauled cow manure into a wheelbarrow and dumped it in a pile up near the creek, then changed the straw in the calf pens. I faked enjoying these tasks because I liked Mr. Tosk. He was short, wide-shouldered and always positive, and he could lift a boiling hot teapot with his bare hands. His nine-year-old son Brodie drove the tractor.

“I like to give the kid responsibility,” said Mr. Tosk, “start him into the real world.”

“Do you think this world is the real one?” I asked him, “or is there more?”

“I go with what I see,” said Mr. Tosk. “But that doesn’t mean there’s not stuff we miss.” He paused. “Ellis, would you operate the silage feed machine?”

“No, too much bad noise,” I said. “I’ll do it by hand.”

I liked digging with the shovel, lifting it heaped and high while I listened to the creek by the farm. The water bubbled up a good noise, natural music to my working rhythm. I wanted to make some sounds just like it.

My friend Jackson played the trumpet. I wanted to play with him, so I bought an eleven-dollar guitar from the pawn shop. I asked Mr. Tosk if he knew anyone who gave lessons.

“I know some guitar,” said the farmer. “I can teach you The Blackfly Song.”

He grinned widely, showing his super-brilliant teeth, as he picked the tune away.

“You have rhythm,” he told me after the first lesson. “And you bite your fingernails. That’s good, keep them short.”

“Does that mean I’m nervous?” I asked. “That’s what my mom says.”

“You should shovel more manure,” Mr. Tosk answered. “That’ll help your nerves… and sing while you do it.”

He hunched over my tiny guitar like a black-haired Bigfoot and played another tune.

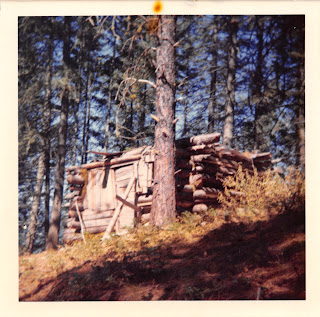

After I learned a few chords, I skipped some school and spent a lot of time practicing music up on the mountain behind the Tosk farm. I bought a double-bladed axe from the pawn shop, hefted it over my shoulder and took it up to a viewpoint. In between songs I chopped down trees and cut the logs into lengths. Then I notched them and started to build a cabin. “I could live there,” I told my friend Jackson. “And escape the bad noise and Mom and Dad.”

“That cabin can be our recording studio,” Jackson said.

“I could bring a girl, too,” I told him.

“You’ll have to talk with one first,” he said.

I nodded. “What should I say?”

“Maybe offer her a sandwich,” he told me. “Or a cigarette.”

“I don’t smoke.”

“Just pretend, like you always do,” he said. “It’s a good way of starting a conversation.”

“I have a girlfriend already,” I told him. “She’s from LA.”

I pulled my wallet out and showed him a photo of a cute brunette.

Jackson studied it a moment.

“That’s from a fashion magazine,” he said.

“No, it isn’t,” I answered.

“I can tell,” he said. “It’s way too glossy.”

“If it wasn’t glossy, it’d be real,” I answered.

“Keep working on that cabin,” said Jackson.

After I’d faked being a drug addict for about a month, I experienced a hallucination episode. The weirdness started in English class. As teacher Al Bianco talked about historical heroes, the blackboard fragmented into pieces, each piece surrounded by a pulsing aura with silver and metallic rings. I rubbed my hands over my eyes and the auras grew.

A wide faced girl named Lorraine sat across from me, big chunks missing from her face. I looked closer and the pulsing pieces of reality filled in for a second, then blurred once more. She turned. “What is it?” she asked, her face half-covered by shimmering silver.

I had to say something.

“Can I borrow a pencil?”

“Sure,” she said. “I’ll give you my red one.”

She pulled it out. I blinked a few times before I could see it well enough to grasp.

I stumbled out of class and up the darkened stairs that led to the school roof, and sat in front of the roof door, holding the pencil in the pitch dark, hoping I wasn’t going blind. After an hour a headache hit, complete with nausea. I pushed the end of the pencil against my forehead, then my temples. I focused on the pencil pain. Even with that, sharp needles drilled right through my eyes.

After an hour, I crept down from the stairs, and I could see clearly again.

I arrived home early and told my Mom I felt too sick to do any chores.

“What’s that horrible red mark on your face?” she asked.

“I’ve got a bad headache,” I said. “I kept seeing flashing lights in front of my face, then my head started killing me and I stuck it with a pencil.”

“You sound like you’re on drugs,” she said. “If your grades keep going down, you’re going to have to pay your way, or Dad’s going to kick you out of the house.”

I wanted to tell her I’d prefer my cabin on the mountain, but she ranted on.

“He told me the other day he’s getting sick of your ‘don’t care’ attitude. Now get out there and do those chores.”

She kept shouting, so I staggered down to my room in the basement, turned out all the lights, and lay there in the dark holding Lorraine’s pencil.

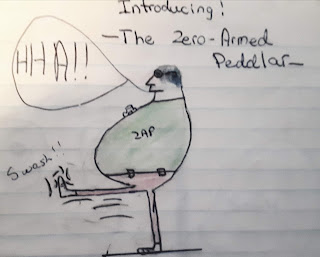

I dozed off. Dreams jumbled through my mind. I awakened to a strange form glowing in front of my eyes, a form in the shape of a short, husky man with no arms who appeared to have a sizeable bottle attached to his chest. The man grinned. He wore an enormous pair of pants tied together by three or four belts, all interlinked. His enormous T-shirt had a logo on it that read ZA. He stank like boiled cabbage.

“My name is Zero-Arms,” he said. “And I’ll be your hero today.” He hopped up and down as he talked. “I’ve come all the way from the Himalayas.”

I glimpsed his teeth, brilliant and silver. When I saw them shimmering, a light flashed in my brain. I jerked forward and fell to one side, found myself halfway off the bed facing the floor.

When I looked up, Zero-Arms faded in the darkness. I heard his voice, talking on in the distance. I waited until the noise and vision residue disappeared, then I pushed myself up, turned on the light, took Lorraine’s red pencil and a sheet of paper and began to draw. I remembered what Mr. Tosk had told me. There are things we miss.

“I have to get this down,” I told myself. “This is proof of a parallel world.”

The next day I showed Jackson the picture.

“It’s detailed,” he said. “I like the guy’s thick neck. What’s the bottle for?”

“It’s called ‘Slime’,” I told him. More information bubbled from my brain. “Zero-Arms sells it for a living. This slime’s what they call a panacea, it’ll heal you no matter what your race, creed, or colour.”

“Zero-Arms peddles slime?” asked Jackson. “That might solve the illegal drug problem.”

He laughed. His face turned purple, and tears flowed down his face. He started coughing, looked at the picture again, and lifted his T-shirt to wipe it over his wet cheeks.

People avoided Jackson. He possessed a mighty physical strength. He’d seem normal, then go into a rage over something very small, like losing a ping-pong game. One time, he threw the whole ping pong table across the gym.

I made it my purpose to know him after a group of guys surrounded me in the change-room. I crouched down with my hands over my head, and they sprayed me with cans of underarm deodorant.

“Take that, stoner,” said their leader, Drew Fleming, a tall braces-faced boy whose mouth resembled a wire mesh.

I lunged forward, broke through the circle, and smelled good the rest of that day.

The next morning Drew tried to trip me in the school hallway. I’d just taken off my outside shoes and didn’t see him coming, but I saw his shadow. I stepped to the side. He missed my foot, tripped, and crashed to the floor.

“Let’s fight!” he yelled as he picked himself up. “Let’s go outside right now!”

His mesh-mouth looked red and swollen.

I shrugged in my fake stoner manner, slid away in my stocking feet, as fast as I could.

“I’ll get you,” he yelled, “maybe not today but sooner or later.”

“If I was friends with Jackson,” I thought, “Drew wouldn’t say that.”

Jackson walked with his massive head pointing down, his big shoulders leading. He smoked a cigarette against the school wall as we waited for the bus. I told him a story about a guy who blew himself up with a set of playing cards.

“He put the cards in a pipe and rested his head and the pipe against a heater and the cellulose in the cards expanded and blew the pipe through his cranium.” I explained.

“You spin a fascinating tale,” he replied.

He offered me a cigarette, and I said I didn’t smoke.

“I fake being stoned, though,” I said.

“That’s a very cool strategy,” he answered, “I often fake being angry.”

Then he chuckled until the tears flowed.

Jackson and I began surreptitiously posting images of Zero-Arms up around the school.

I’d draw the hero, huge head with mop-top hair and a smile like a reverse question mark. I’d write a caption underneath; Jackson filled the extra space in with sketches of students and teachers.

In the captions, Zero-Arms said things like “Tired of studying? Have some Slime,” or “I have no arms, but I know French foot fighting techniques.”

One Friday midnight, Jackson and I loped down to the outdoor baseball enclosure. We carried cans, with five different colours of paint.

“It’s a humongous world out here,” said Jackson. “We’ll create a picture to match.”

We began to work. A seven-foot-high image of Zero-Arms and his four belts quickly materialized on the plywood backboards, the prominent chest-bottle popping forward from his center. I used luminous yellow on top, so he’d glow at night.

“Have some slime,” the caption read.

We sat back on the bleachers and admired the massive cartoon. I couldn’t tell if it was glowing or not.

“You should put some luminous on your cabin door,” Jackson suggested, “So you can find your place in the woods at night.”

The cabin already stood twelve logs high. I laid poles across the top. A flat roof was much easier, and I wanted to finish. Jackson arrived to check it out and play the trumpet. On the way back down, we passed Mr. Tosk and Joey rolling by on their tractor. Brodie stopped and Mr. Tosk yelled above the engine din, “How’s the rhythm?” and I said, “Excellent.”

Brodie jerked the machine forward and roared off. Mr. Tosk waved his hand back our way.

“That farmer guy looks exactly like Zero-Arms,” said Jackson, “except he has arms.”

“I never thought of that,” I said.

“It’s his face and neck that’s the same,” said Jackson, “he’s smiling like a question mark, and he’s got that huge head.”

“Tosk never criticizes me,” I said. “He’s a man of peace and music.”

“You shovel shit for him, is that correct?” Jackson asked.

“I like the rhythm,” I said, “that’s where I learned guitar.”

A few mornings later Mr. Bianco, the English teacher told us “We’ve been studying heroes for a while. Today I’d like you to write about your own heroes.”

He went on about how it’s good to have a role model to look up to, how every teenager should have a mentor. I couldn’t think of any except Mr. Tosk, but he was too real.

I began to scribble down the tale of Zero-Arms.

The next day Bianco asked us to read our stories out.

“Your turn, Ellis,” he said. “I guess as usual you haven’t done your homework.”

I paused, as part of my stoner act, then spoke slowly.

“I’ve got five pages here. My hero is a creature named Zero-Arms who walked as an embryo out of the South Pacific just after the 1952 US H-bomb test. As soon as he contacted land, his body developed strangely because of his radioactive genes. He grew mighty eagle wings, on which he soared around the world trying to create world peace, due the trauma he suffered from the H-bomb effects, but the warmongers caught him and cut off what they called his ‘mutant limbs.’ After this, he became known as Zero-Arms, and retreated to live in the Himalayas where he met the Anthrops, a secret group of aliens stranded in a cave for several hundred years because they couldn’t exist in direct sunlight. The Anthrops gave Zero-Arms the recipe for the amazing healing product called “slime,” made from mushrooms and bat guano. Slime can heal anything.”

Bianco cut me off.

“This is highly imaginative,” he said, “but do you have any real heroes?”

“He’s real to me,” I said.

“Hand it in,” he told me, “I’d be very interested in reading the rest.”

In the cafeteria after class, Lorraine sauntered up, chewing on a tootsie-roll.

“Do you have my red pencil?” she asked. “You borrowed it some time ago.”

“Um, yes,” I said, “but it’s at home.”

She grinned. “Where did you get those ideas about a hero with no arms? Everyone was killing themselves laughing.”

“Well, I had a kind of vision dream of him the day I borrowed your pencil,” I told her, “And when I woke up, I used it to draw what I saw.”

“You looked sick that day,” she said, “I was glad you didn’t upchuck.”

“Well,” I told her, “When I was asking you for the pencil, I had this blurry vision and kind of a glowing around everything.”

Lorraine nodded. “Did you get a real bad headache afterwards?”

“I sure did.”

“That’s a migraine,” she said. “I get them about once every couple of months. They suck.”

“My Mom thought I was on a drug trip,” I said. “I used your pencil to push out the pain.”

“Do you take drugs?” Lorraine asked.

I thought a moment. Lorraine’s eyes looked big and curious and more than a bit sexy.

“I say no to drugs,” I said.

She nodded. “Yeah, I thought it was an act.”

“What was an act?”

“Well,” she said, “you always act so obviously stoned, like TV Cheech and Chong, and you never hang around with the real stoners. You hang around with Jackson.”

“Jackson smokes,” I said.

“Yes,” she replied. “He keeps offering me cigarettes.”

The next day teacher Bianco called me into his office. I looked at his red hair flying forward from his forehead, and his very square and forward sloping teeth.

“Tell me,” He said, “are you the one putting up all those cartoon posters around the school?”

“What makes you ask that?” I asked.

“Because I read this,” Bianco held up my Zero-Arms essay. “Your description matches the evidence on the walls.” He sighed. “You’re very immature. You live in a child’s imaginary world. I think you wanted to get caught, so you could tell all your friends. Did you get a kick out of the response to your essay?”

“I don’t have many friends,” I said. “I’m building a cabin in the woods.”

Bianco kept talking.

“Most kids put their mom or their dad down as their hero. Why didn’t you put your dad down?”

“I don’t know if I could write a lot about them,” I said.

“Maybe that’s because you don’t see their values and strengths,” he told me. “You’re too caught up in your own child’s world. You’re very creative, but what practical use is this, except as a joke?”

He pointed at the essay and leaned forward. “I don’t want to see any more of those posters. The principal has been notified.”

I looked carefully at Mr. Tosk during our next guitar lesson. He strummed a Corsican folk song. It sounded pretty good.

“Maybe in that vision I had,” I thought, “That guitar became Zero-Arms’ bottle of slime.”

Mr. Tosk put the instrument down.

“You said you wrote something,” he said. “I’d like to hear it.”

Jackson and I had practiced this original number up at the cabin. We called it “Child of The Mountains.”

“I don’t have all the chord changes down exactly yet,” I said.

“Let’s hear it anyway,” said Mr. Tosk. He lifted his boiling hot teapot with his bare hands and poured himself another cup. “I’d like to get the rhythm.”

I took the guitar. I’d never sung for anyone before except Jackson. My fingers still didn’t have callouses. I played as best I could.

“Child of the Mountains, hidden by the sun, will you ever see the grass of home?”

“Sounds like you wish for a better world,” said Mr. Tosk, as I finished. “A peaceful one that the singer’s looking for. But what is the grass of home?”

“I’m not a drug addict,” I said. “Maybe I should change that.”

“Keep making up those songs,” Mr. Tosk told me. “Music’s a good way to find your rhythm.”

In English, Mr. Bianco handed out copies of “Lord of the Flies.”

“This is a short book about true human nature,” he said.

I tapped Lorraine’s desk with her red pencil.

“Here you go,” I said.

She reached out and grabbed it. I showed her the drawing of Zero-Arms I made the night he appeared.

“This fellow came out of my migraine,” I said, holding the paper low to the floor.

In the cafeteria, Lorraine put her own piece of paper down on the bench.

“It’s a poem I wrote,” she said, “The Ferity of Her. Ferity means “wildness.” Check it out.”

I read a few lines. They didn’t make a lot of sense.

“You like different words too,” I said.

She grinned a grin that went up on both sides like two joined-together musical notes.

“Stuff that’s different is fun,” she told me, “And interesting. Can I see that drawing again?”

“Okay,” I said. Then I asked, “Do you think we’re immature?”

“How do you mean?”

“Well, Mr. Bianco read my essay and he said I was like a child making things up in my mind. He said having fake heroes wouldn’t lead anywhere.”

Lorraine nodded. “You are a child,” she said, “a child of the universe. No less than the trees and the stars, you have a right to be here.” Then she grinned. “I quoted that.”

“Who did you put down as your hero?” I asked.

“My mom,” she said.

I went home and my mom and dad were in the newly plowed garden, picking up roots and stones.

“Can I help out at all?” I asked.

“You never ask to help,” Mom said. “Did you win the lottery?”

“I’m building a cabin back of the Tosk place,” I said.

Dad took the cross-axe and chopped off a long root. I’d seen him do work like this for most of my life.

“Is it on his land?” he asked.

“What?” I asked.

“The cabin,” he said, “is it on Tosk’s land?”

“It’s way back in the bush,” I told him, and started picking up some stones.

“You could help some more around here,” said my mom, “instead of always doing your own thing.”

Dad stood up. “I’d like to see that cabin,” he said, “when it’s done.”

“Sure,” I said. “Sorry I’m not much into fishing.”

“As long as you’re not doing drugs up there,” Dad said. “Those drugs will poison your mind.”

I nodded and picked up rocks and roots for the next two hours and thought of how to construct my cabin fireplace.

I planned to build it out of rocks from the creek, and mortar from the building shop. It would be heavy hauling the dry cement up there. Lorraine and Jackson came to visit. I asked for their fireplace advice.

“I don’t know how this is going to work,” said Jackson, “there’s a lot of holes.”

I’d fished some old sheet metal funnels from the garbage dump and stuck them together to make a chimney.

“It’ll be like a campfire inside,” I said. “Most of the smoke will got out the top.”

“This is a real spiritual location,” said Lorraine.

She put down her pack-sack full of tootsie rolls and poems. “I see you have a bunch of Zero-Arms posters on the walls.”

“They don’t allow them in school anymore,” said Jackson.

He blew his trumpet. The sound roared across the ridge and down towards the valley.

“When Jackson blows his trumpet, he looks exactly like Zero-Arms,” Lorraine said. “Especially with that strong neck.”

“It’s too bad we don’t have some of the fat peddler’s slime,” I told her. “We could all lie back and feel peaceful.”

“I feel peaceful,” said Lorraine, “except for that music.”

“I like to blow my horn,” Jackson grinned.

Lorraine passed me a photo.

“Wow, that’s a pretty good picture,” I told her.

“That’s me,” she said. “I once tried out for a fashion catalogue.” She grinned. “You can keep it. I’ve got about fifteen copies.”

I bought out my guitar to play “Child of The Mountains.”

“This is the only song I know at this point,” I said.

Lorraine sat on a stump. “We’re lucky,” she told me. “We’re lucky to have all this.”

She waved her arms around at the pine trees and the long brown grass that grew on the hillside.

“I feel like a wild mustang, free and strong!” she yelled.

I watched her hair and hips swing, noticed most her wide note smile, and her teeth, gleaming bright.

“Yes, this is real,” Jackson answered, sitting down on a rock and pulling out a cigarette.

The next day I sat in the baseball field bleachers and meditated on the seven-foot-high poster of Zero-Arms.

“The hair looks like Jackson’s,” I thought. “It’s thick at the sides, with a sudden cut below the sideburns,” although Jackson didn’t have any sideburns.

Drew Fleming and his sidekick, Jorgenson Lewis, came into the stadium.

“We’ve been watching you from the car,” Fleming said. “Is that your poster? Lorraine told my sister you’ve been putting them up all over.”

“Just some kind of weird luminosity,” I said.

“You owe me,” Drew said, “for tripping me in the hall back at Easter time.”

“Your friend Jackson isn’t here to help you,” Jorgenson added.

I looked at the picture of Zero-Arms. What would he do? He was a person of peace, yet I wasn’t going to let Drew pull my wings off, like the warmongers did to Arms.

“You guys are acting like Lord of The Flies characters,” I said. “Why don’t you try something original?”

“You’re not a stoner,” Jorgenson said. “You’re just weird.”

“If I had my underarm deodorant,” said Drew, “I’d spray you all over.”

I let them come for me. It didn’t matter. I had a hero in Zero-Arms, friends in Jackson and Mr. Tosk, and maybe even a girlfriend in Lorraine. I built a cabin in the mountains and wrote a song about it. I helped my parents pick rocks and roots, but if Dad kicked me out of the house anyway, I’d have a place to go. Like Lorraine said, I was very lucky. I thought of Mr. Tosk and concentrated on rhythm, dancing around with my fists out and yelling “You want slime? I’ll give you some slime!”

The bullies tried a few swings, Jorgenson hit me on the jaw, and I slammed him in the nose. He backed off. Drew picked up a rock and threw it.

“We’re gonna spray paint over that artwork!” he yelled.

“Wow,” I thought, “they think its artwork.”

The trees in the distance turned blurry. Glowing cracks appeared in the grass, and as I looked at Zero-Arms’ poster, sliver shimmers played around it.

“Jorgenson didn’t hit me that hard,” I said.

For the moment, I didn’t think about the migraine to come.

I anticipated the vision that might arrive after that.

“I will see that other world again,” I thought.

I couldn’t wait. Inspiration for my life and my future lay over there. I needed my hero to show me, once more, that we were both real.