After years of behind-the-scenes activity in the Gaza Strip, Egypt is going public.

Since mediating a cease-fire between Israel and Gaza’s ruling Hamas militant group, Egypt has sent crews to clear rubble and is promising to build vast new apartment complexes. Egyptian flags and billboards praising President Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi have sprung up across the Palestinian territory.

It is a new look for the Egyptians, who have spent years working quietly to encourage Israel-Hamas truce talks and reconciliation between rival Palestinian factions.

The shift could help prevent – or at least delay – another round of violence. By presenting itself as a Mideast peacemaker, Egypt could also blunt efforts by the Biden administration and some United States lawmakers to hold the country accountable for human rights abuses.

The 11-day Gaza war last May “allowed Egypt to once again market itself as an indispensable security partner for Israel in the region – which it is – which in turn makes it an indispensable security partner for the U.S.,” said Hafsa Halawa, an expert on Egypt at the Middle East Institute, a Washington think tank.

“Gaza is a reminder to everybody, effectively, that you can’t really do anything without Egypt,” she said.

The expanded aid, along with its control over Rafah – the only Gaza border crossing that bypasses Israel – gives Egypt leverage over Hamas, the Islamic militant group that has ruled Gaza since driving out forces loyal to the internationally recognized Palestinian Authority in 2007.

Egypt joined Israel in imposing a crippling blockade on the territory after the Hamas takeover, but both countries have recently taken steps to ease the restrictions, tacitly acknowledging that Hamas rule is here to stay.

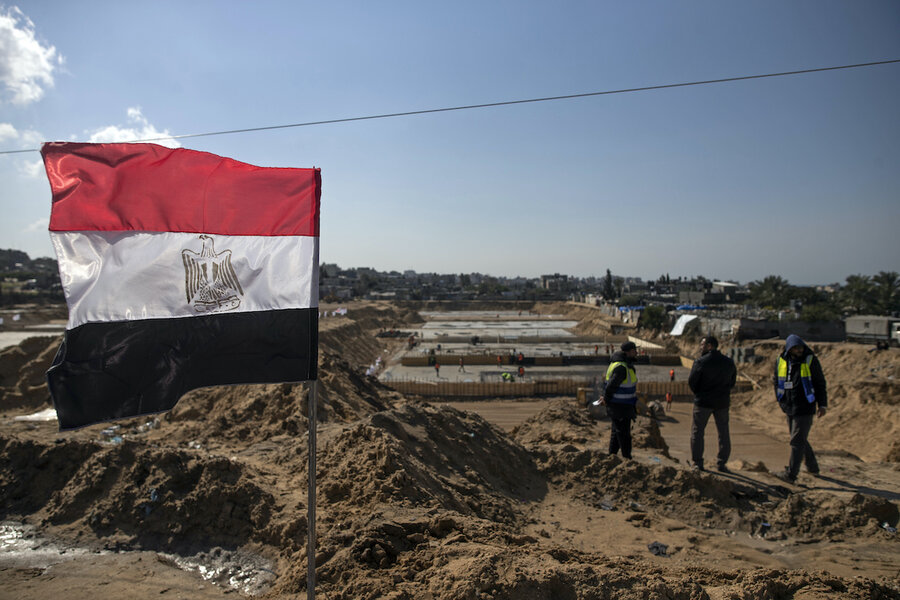

After negotiating the informal cease-fire that ended the Gaza war, Egypt pledged $500 million to rebuild the territory and sent work crews to remove rubble.

While it remains unclear how much of that money has been delivered, Egypt is now subsidizing the construction of three towns that are to house some 300,000 residents, according to Naji Sarhan, the deputy director of the Hamas-run Housing Ministry. Work is also under way to upgrade Gaza’s main coastal road. Mr. Sarhan said the projects will take a year and a half to complete.

“We hope there will be large bundles of projects in the near future, especially the towers that were destroyed in the war,” he said.

Israel leveled four high-rises during the fighting, saying they housed Hamas military infrastructure. It has not publicly released evidence backing up the claims, which Hamas denies. The construction materials will be shipped through Rafah.

Alaa al-Arraj, of the Palestinian contractors’ union, said nine Palestinian companies will take part in the Egyptian projects, which would generate some 16,000 much-needed jobs in the impoverished territory.

The Egyptian presence is palpable. Nearly every week, Egyptian delegations visit Gaza to inspect the work. They have also opened an office at a Gaza City hotel for permanent technical representatives.

Egyptian flags and banners of Egyptian companies flutter atop bulldozers, trucks, and utility poles. Dozens of Egyptian workers have arrived, sleeping at a makeshift hostel in a Gaza City school.

Five days a week, Egyptian trucks filled with construction materials flow into Gaza through the Rafah crossing – a visible contrast to the intermittent shipments arriving through an Israeli-controlled crossing.

Suhail Saqqa, a Gaza contractor involved in the reconstruction, said the steady flow of Egyptian materials is critical.

“The goods are not restricted by Israeli crossings, and this makes them momentous,” Mr. Saqqa said.

The projects are part of a broader realignment after years in which Gaza was caught in a tug-of-war among Arab states following the upheaval of the 2011 Arab Spring protests.

A short-lived elected Islamist government in Egypt was closely allied with the Gulf country of Qatar and sympathetic to Hamas. It eased the blockade and brokered the end of a brief Gaza war in 2012. But the following year it was overthrown by the Egyptian military.

The Egyptian leader, el-Sissi, who led the overthrow, initially adopted a hard-line stance against Hamas, ordering the destruction of a vast network of smuggling tunnels that had sustained Gaza’s economy.

Qatar, which supports Islamist groups across the region, meanwhile stepped in to provide humanitarian aid, including cash-filled suitcases shipped to Gaza with Israel’s permission.

The rivalry escalated, with Cairo joining the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Bahrain in blockading Qatar from 2017 until a year ago. But relations have improved, and Egypt and Qatar are now cooperating to deliver aid that helps the Hamas government pay its civil servants.

The growing Egyptian role gives Cairo a powerful tool to enforce Hamas’ compliance with the truce. It can close Rafah whenever it wants, making it nearly impossible for anyone to travel into or out of Gaza, which is home to more than 2 million Palestinians.

Egypt “can suffocate Gaza in a moment” if its demands are not met, said Maged Mandour, an Egyptian political analyst.

That might be enough to prevent another outbreak of hostilities in the near term. But it doesn’t address the underlying conflict that has fueled four wars between Israel and Hamas and countless skirmishes over the last 15 years.

Israel and most Western countries consider Hamas a terrorist organization because of its refusal to accept Israel’s existence and its long history of deadly attacks.

Israel has enforced a policy of separation between the Israeli-occupied West Bank and Gaza, which flank Israel and under an internationally endorsed proposal would one day be part of a Palestinian state.

Israel’s current government has ruled out any major peace initiatives – even with Western-backed Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas in the West Bank – but it has taken steps to improve living conditions, including issuing some 10,000 permits for Gazans to work inside Israel.

Relations between Hamas and Mr. Abbas’ Fatah party plunged to a new low last year after he called off the first elections in more than 15 years. Repeated attempts at reconciliation – many brokered by Egypt – have failed.

But for Egypt and Israel, and for a U.S. administration focused on larger crises elsewhere – preserving the status quo in Gaza might be enough.

“Egypt wants understandings or even pressure on Hamas so the situation won’t explode,” said Talal Oukal, a Gaza-based political analyst.

This story was reported by The Associated Press. Mr. Akram reported from Hamilton, Canada. AP writer Joseph Krauss in Jerusalem contributed to this report.